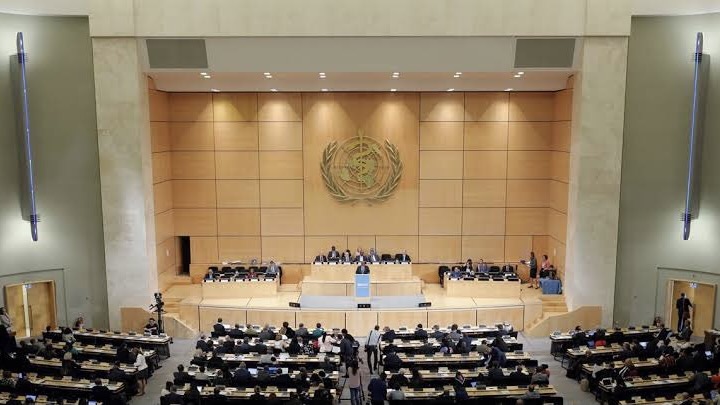

The World Health Organization (WHO) is convening a World Health Assembly Special Session (WHASS) between November 29 and December 1, 2021. The WHASS will be considering the benefits of developing a WHO convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemic preparedness and response with a view towards the establishment of an intergovernmental process to draft and negotiate such a “new instrument”.

The WHASS will be conducting its agenda by taking into account the report of the Working Group on Strengthening WHO Preparedness and Response to Health Emergencies (WGPR), which proposes to establish a new intergovernmental negotiating body to be in charge of the development of the new instrument. Although the report is not specifically suggesting to develop a new international convention, a group of Member States of WHO, identified as a Group of Friends of a Pandemic Treaty, primarily led by the European Union (EU), is promoting a proposal for a new “treaty” on pandemic preparedness and response.

While a new treaty proposal seems to be an attractive call, especially since many civil society organizations and research organizations presume it as an additional opportunity to further pursue their unfinished agendas on equitable access to health care and open innovation relating to public health, the dangers of this path are hidden in the details. The proposal and negotiations turn the attention of the international community away from the many existing issues relating to international health emergencies such as continuing opposition to TRIPS waiver proposal, disruption of international cooperation in the immunization against COVID-19 viruses and the need for reforming and strengthening existing instruments and mechanisms to address the health emergencies in general such as International Health Resolutions (IHR) 2005.

Negotiations so far

The pandemic treaty was proposed to the world much ahead of various expert committees and review panels constituted under the WHA Resolution 73.1 to review the functioning of the WHO and countries during COVID-19, as well as the implementation of International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005 tabled their findings and recommendations.

WGPR, which was later constituted to consider the findings and recommendations of these committees, was then mandated to assess benefits of developing a WHO convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemics via decision WHA74(16). After 5 rounds of official meetings and 4 informal consultative meetings, the WGPR has now returned to the WHASS with a proposal to establish an intergovernmental negotiating body to be in charge of developing a new instrument on pandemic preparedness and response, but without specifying whether it should be a treaty or not.

This is relevant as the WHO, according to its Constitution, can adopt legal instruments which differ in some aspects. For example, a convention or agreement adopted under Article 19 of the WHO Constitution can become binding only on those member states who will ratify it using their constitutional machinery. Differently, an instrument that is adopted under Article 21 becomes binding to all Member States of WHO automatically without such a ratification, except for Member States which explicitly notifies WHO an opting out from the instrument. Article 23 instrument, in contrast to Article 19 and 21 instruments, is a soft law instrument.

Since the countries in the WGPR did not take into consideration the above mentioned aspects of different instruments in a relative manner, WGPR did not arrive at a consensus on any specific type of instrument. In this sense, the WGPR report shoots in the dark, by proposing WHA to launch an INB to negotiate the new instrument, without a clear idea of what instrument it should be. It is anticipated that some member states from friends of the treaty group, would try to get a decision from WHASS in favor of launching a treaty negotiation process.

If the WHASS adopts the proposal made by WGPR to establish INB, there will be at least two bodies working on reforms of international health emergency laws. WGPR will continue to work on the findings and recommendations of expert committees and panels; with a view of developing specific action points, including amendments to existing laws, especially IHR 2005. And there will be an intergovernmental negotiating body, developing a specific instrument for pandemic preparedness and response.

If these two negotiating bodies function concurrently, there is every chance that the attention of the developing countries will get diluted, especially those maintaining smaller delegations. The synergy between these bodies will also become a crucial concern, as lack of it leads to incoherence between IHR 2005 and the new instrument on pandemic preparedness and response.

Expanding existing health inequities?

The scope of IHR 2005 is wide enough to cover all forms of international health emergencies in general, and IHR calls for internationally coordinated preparedness and response. Nevertheless, IHR 2005 still continues to function as an instrument that carries remnants of the colonial perspectives on health law and policy, and in practice, its provisions are clearly skewed against the interests of the developing countries. This problem could be expanded even more by a new international instrument.

Firstly, if IHR promotes verticalization of public health policy, the pandemic treaty super-verticalizes this agenda. The objective of the IHR 2005 is to address the international spread of the disease, quite narrower in scope than from the general function of WHO to eradicate epidemic, endemics and other diseases. The new pandemic treaty proposal brings this to a new level: for example, equitable remedies against public health emergencies of international concern (PHEIC) like Ebola may not be covered under the new treaty. The WGPR report interestingly does not speak anything about the scope of pandemic preparedness and response.

Secondly, the duty to collaborate and assist in IHR 2005 is traditionally considered as a persuasive one. By using such an interpretation the developed countries get away with all their noncompliance with duty to cooperate under IHR, without much political or legal impediments. They make use of the information and pathogens shared by the developing countries, close their borders to the people and goods from affected countries, let their pharmaceutical businesses develop and produce diagnostics, medicines and vaccines, create monopolies over such products using patents, immunize their populations first even though they are not as vulnerable as countries primarily infected, and then later sell the medicines and vaccines to these affected developing countries with high margins of profit. The world is saved; but the economies of the developing countries are further shrunk.

This is an issue of incredible importance for developing countries in the implementation of IHR 2005, yet the pandemic treaty cannot do anything to effectively address it. In order to change this, developing countries should focus more on IHR targeted amendments – but their attention has already been diverted to the pandemic treaty proposal.

Thirdly, a securitization agenda is also on the push, i.e. to get access to outbreak sites, but during WGPR negotiations equal importance to sovereignty concerns were also recognized. Whether this will be upheld in future negotiations remains to be seen. Currently, under IHR 2005, on-site access is very limited and is only through state party consent or request.

Finally even in the proposed pandemic treaty, the possibility remains to accommodate equitable principles in the so-called persuasive or hortatory fashion. An Article 19 pathway, allows developed countries to keep the text of treaty without ratification if provisions on equity gets concrete and definite design, against their interests. A framework convention model could offer more scope to developed countries to get certain quick agreements – “quick wins” – on certain areas of their interests and leave rest of the matters to the future negotiations. To give an illustration, “rapid sharing of pathogen or genetic information on a real time basis” may be incorporated in the parent framework convention itself, as a clear and objective prescription of law, while concerns relating to duty to cooperate such as equitable access to health care, or diversification of the production of health technologies may be pushed into protocol instruments to be negotiated on a later date.

The European Commission’s reflection paper is very well reflective of this agenda. It proposes to use a flexible and open participation model for the pandemic treaty, as well as a mix of soft-law and hard-law mechanisms. To guard against these dangers, Brazil has insisted that any further discussion on new treaty, convention or any form of instrument, should address the concerns of equity first.

But given the current balance of power, it still cannot be said that keeping equity on top of the list will be an outcome of the pandemic treaty proposal process. What seems possible, in fact, is that it will move in the opposite direction of IHR 2005, seeking to delink the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing that assures states’ sovereignty over genetic resources, including pathogens, from health emergency laws. IHR mandates that any transfer of biological samples and pathogens should abide by the provisions of the Nagoya Protocol, but it seems the current Pandemic Treaty Proposal is pushing in the direction of rapid sharing of health information, including digital sequence information of pathogens, which can bypass the application of Nagoya or other related provisions.

In short, the proposal for a Framework Convention on Pandemic Preparedness and Response under Article 19 of the Constitution of WHO leaves very limited scope for developing countries to achieve anything immediately, while they may be forced immediately to further shrink their sovereignty over outbreak sites and pathogens causing pandemics.

Read more articles from the latest edition of the People’s Health Dispatch and subscribe to the newsletter here.

Nithin Ramakrishnan is a postgraduate in International Law and a visiting faculty at Chinmaya Vishwavidyapeeth (Deemed to Be University) Kochi. He closely follows the WHO and IHR Implementation.