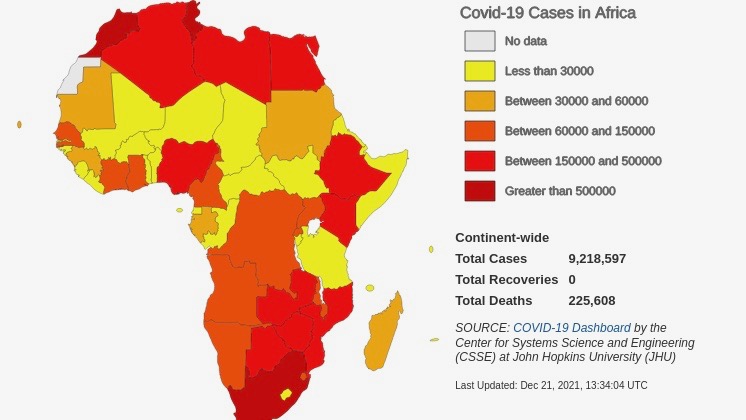

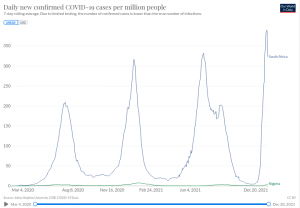

With both Delta and Omicron variants spreading across Africa, which is currently facing the fourth wave of the pandemic, the total cases of COVID-19 detected on the continent crossed 9.2 million on December 21. This is an increase of 52,308 cases in the 48 hours. In total, 226,047 deaths have been reported while 8,344,234 people have recovered.

The real extent of the spread is bound to be many times higher. The WHO had estimated based on an analysis in October that the real number of infections in Africa was “seven times more” than the reported cases. The same analysis also concluded that two-thirds of the deaths due to COVID-19 remain unreported.

Official data not only understates the extent of the spread, but also paints a misleading picture when it comes to the concentration of cases in different parts of the continent. With 3,316,585 registered cases in South Africa as on December 21, official data shows that over a third of all the cases on the continent are concentrated in this country, followed by Morocco with 952,916 cases, Tunisia (721,103), Libya (382,341), Ethiopia (377,056) and Egypt (376,233).

Nigeria, which has the continent’s highest population – about four times that of South Africa both in terms of numbers and density – ranks a distant eighth with only 225,255 reported cases. This is because “testing in Nigeria is way below par being one of the lowest per capita testing in Africa while testing in South Africa is way above the continent’s average,” Dr. Ahmed Kalebi, president of the East African Division of International Academy of Pathology (IAP), told Peoples Dispatch.

“The reasons for this disparity include the state of the health systems and funding for the COVID-19 testing. Nigeria has virtually dismal COVID-19 public health response,” he said. “Without accurate and updated data including on testing, genomic surveillance and hospitalization rates, the approach to dealing with the pandemic in Africa is like a rudderless ship sailing in uncharted waters. That is the sad reality,” he added.

Leslie London, professor of public health at the University of Cape Town and an active member of the People’s Health Movement South Africa (PHM SA), added, “Without accurate data, it is hard to know the burden of the disease, how effective your strategies are, where to target them, whether vaccination is working, etc. All of these are key questions and if you don’t have a good handle on infection (rates), and rely on hospital admission data, you are clearly limited.”

However, despite the lack of reliable data on infections, an accelerated and systematic vaccination campaign can still be effective in combating the pandemic, argues Lauren Paremoer, also an active member of PHM SA and senior lecturer in the Political Studies Department of University of Cape Town.

“Even if African states have inaccurate data on COVID-19 prevalence, they do have fairly accurate data on the proportion of adult citizens in their population,” she told Peoples Dispatch, explaining that this is the key information needed to undertake a vaccination campaign.

The vast majority remain unvaccinated as richer countries continue to hoard

The main impediment in the way of the vaccination campaign remains the acute shortage of vaccine supply in Africa due to hoarding by wealthier countries. As of December 14, only two of the 55 African countries, the small islands of Mauritius and Seychelles, had successfully vaccinated 70% of their populations, which is regarded as the minimum required to control the pandemic. Vaccinating 70% of Africa’s population requires 1.6 billion more doses, which will not be available any time soon.

A pandemic assessment by WHO last week calculated that at the current pace, the 70% mark may not be reached until August 2024, almost two years later than May 2022 which was set by WHO as the global target deadline to reach this level of coverage. WHO has set a minimum 40% vaccination target for all countries by the end of this year. Only six African countries have met this target.

With only 8.64% of the continent’s population fully vaccinated and 12.57% vaccinated partially, the vast majority of the continent remains unvaccinated and highly vulnerable to the new waves expected to emerge. Only 20 of the African countries have been able to vaccinate at least 10% of their population.

“We’ve known for quite some time now that new variants like Beta, Delta or Omicron could regularly emerge to spark new outbreaks globally, but vaccine-deprived regions like Africa will be especially vulnerable,” Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, said last week.

“In a world where Africa had the doses and support to vaccinate 70% of its population by the end of 2021—a level many wealthy countries have achieved—we probably would be seeing tens of thousands of fewer deaths from COVID-19 next year,” he said.

Earlier this month, WHO’s director of the Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals, Kate O’Brien, warned that even though the supply is increasing, vaccine hoarding by wealthier countries in light of the new variant may reverse any hope offered by ramped up production.

“As we head into whatever the Omicron situation is going to be, there is risk, that the global supply is again going to revert to high-income countries hoarding vaccines to protect, you know, in a sense, in excess their opportunity for vaccination and a sort of ‘no-regrets’ kind of approach,” she said.

This policy of hoarding by Western governments to protect their own populations is “not going to work from an epidemiological perspective, it is not going to work from a transmission perspective unless we actually have vaccines going to all countries, because where transmission continues… that’s where the variants are going to come from,” she stressed.

In addition to ramping up vaccine supply to Africa, Moeti also stressed on the need to “intensify our focus on other barriers to vaccination,” including the lack of “cold chain capacity” and other equipment.

Successful vaccination campaign needs holistic approach

Due to shortage of cold chain capacity, accessibility of vaccines remains restricted in large parts of even those countries that have received the required doses for their population, explained Dr. Kalebi. “In many of the countries where vaccines have been received.. you find large parts of the country still lacking access to vaccines because of lack of infrastructure and logistics,” he said.

“For example, in Kenya, the Pfizer vaccine is only available in select centers in the capital city of Nairobi because of the -80 degrees freezers and special syringes/needles being unavailable (outside). Even for the other vaccines that require -20 freezers, the distribution of the vaccines is limited to areas with the cold-chain and therefore many parts of the country are excluded from the vaccine coverage.”

The lack of cold-chain services and other equipment and facilities required for a successful vaccination program is a problem that cannot be solved in isolation from the broader issue of infrastructure deficits on the continent.

“Without addressing the broader social determinants of health – such as electricity and water supply, public transport and specialized transport for people who cannot move around easily, and safe and conveniently located vaccination sites, vaccination efforts will be difficult,” Paremoer said.

“Addressing these broader infrastructural issues is crucial for improving health outcomes generally. With the increased commercialization of basic goods and services like electricity and water, many communities are struggling to access these services which are crucial to daily activities – bathing, cleaning, food preparation, internet and phone connectivity – which are the cornerstones of psycho-social and physical welfare.”

IMF’s prescription to African governments led to contraction of health budget amidst pandemic

A comprehensive approach to the pandemic which addresses the broader weaknesses of the healthcare system and underdeveloped infrastructure requires a commitment of significant resources from the budget. Most African governments, under the thumb of the IMF, remain hesitant to do so.

After a meeting in Senegal’s capital Dakar earlier this month, IMF’s managing director Kristalina Georgieva said that she was “encouraged by the commitment of Ministers from the region to pursue well-targeted policies consistent with the maintenance of macroeconomic stability and a robust medium-term reform agenda.”

“The countries in the region,” she reiterated, “should continue to address the health crisis, while ensuring that policies are well-targeted and consistent with the maintenance of macroeconomic stability.”

“The above language asks the governments to prioritize the well-being of abstractions like “economic indicators” instead of the well being of actual people,” said Paremoer.

IMF’s prescription for macroeconomic stability, in South Africa for instance, has “despite the pandemic, translated into a contraction of the budget allocated to the health sector, the phasing out of state-sponsored bursaries for nursing students, and the continued exploitation of the community of health workers who are poorly paid and have very difficult working conditions,” Paremoer added.