Serbia’s health system was the focus of an unusual amount of interest last March, as musician Konstrakta entered the Eurovision contest with a song on access to health care among artists. The existing health insurance model is supposed to guarantee near-universal access to workers and their families. Yet, in practice, those who do not have full-time, permanent employment struggle to access this care. The discussion sparked by Konstrakta’s song died down quickly, but the problems it highlighted did not.

Access to healthcare in Serbia was a cause for concern among researchers long before it was sung about. Among the many problems that characterize health system, including regional disparities in infrastructure, the working conditions of those in the sector is a major one. While most analyses of the local pandemic response highlight the contribution of health workers, this recognition still fails to translate into concrete policy solutions.

Capping employment during shortage of workers

According to data collected by the Trade Union of Physicians, Pharmacists and Dentists, more than 100 doctors, pharmacists and dentists died from COVID-19 during the first year of the pandemic. To this number, one should add dozens more among nurses and other health professionals.

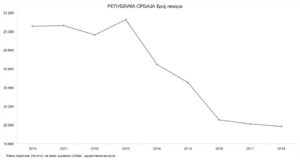

The recorded number of deaths among health workers is significant in itself. It becomes even more so when one considers the precarious position in which health workers found themselves even before the pandemic. Before the onset of COVID-19, the Trade Union of Physicians, Pharmacists and Dentists estimated that the health system faced a shortage of around 8,000 physicians. Instead of introducing policies turned towards training and retaining new workers in the public health system, the government introduced a cap on new employment in 2014.

Unsurprisingly, there was a 5% decrease in the number of family physicians and junior doctors from then until 2019. The decrease corresponds to approximately 10,000 fewer workers in the health system, as reported by portal Nova ekonomija in 2019. This included 1,000 physicians and as many as 3,000 other health professionals.

Alarms were sounded early on by policy analysts and civil society about the potential damage from such an employment policy. Yet no significant change was implemented even as COVID-19 began spreading. According to local activists, the government did not even acknowledge the problem. Instead, when the number of physicians is discussed in public, ministry officials cite official data from the Serbian Medical Chamber (SMC) – putting the total number of doctors in Serbia at over 30,000.

What is missing in the picture is the fact that this number includes everyone who holds a medical license. The register of the SMC lists physicians practicing in the public system, but also those who are unemployed, working in the private sector, or who volunteer on a temporary basis. Because of this, the figure says very little about whether it is actually easy for people to reach a doctor when needed.

Unmet needs expand during the pandemic

The health workforce situation is indeed creating problems in practice. On the one hand, health workers are overworked and more prone to falling ill themselves. On the other hand, many patients experience difficulties accessing care because they are forced to travel or to pay for care in the private sector. During COVID-19, such barriers to access to care have only expanded and concerns remain as to whether it will be possible to resolve them in the future.

A recent publication by a group of researchers from the University of Belgrade’s Institute of Social Medicine focused specifically on access to different forms of care in Serbia during the pandemic. Their analyses show that the past two and a half years led to a decrease in people accessing care in public health institutions, especially when it comes to specific population groups.

Aleksandar Stevanović, the editor of the publication, reports that there was almost a 17% drop in visits to primary level practitioners in 2020 compared to the year before. This raises the question about a possible rise in unmet health needs, which is more frequent among the poor or in disadvantaged regions, like Serbia’s south-east.

Zooming in on specific aspects of healthcare brings out even more worrisome data. There were almost half a million fewer women who visited their primary-level gynecologist in 2020 compared to 2019, and 35% fewer women attended preventive check-ups.

According to Jovana Todorović, Stevanović’s department colleague and author of the study’s chapter on women’s health, this is not the only way in which women’s health was affected during the pandemic. She goes on to explain that 7% of women compared to 4% of men lost their jobs during the pandemic. This added to socioeconomic insecurity and, through that, led to an erosion of mental health.

Additionally, women were more exposed to extreme amounts of stress than men. In her article, Todorović highlights that most of the health workers in Serbia are women. That means that the health of women in Serbia is not only undermined by obstacles to access to care, but also by the extreme working conditions in the public health system. Ensuring proper workforce policies and investing more in strengthening working conditions would therefore have a positive double effect on women’s health: making healthcare more easily accessible to women who need it, and protecting the health of women in their workplaces in the sector.

People’s Health Dispatch is a fortnightly bulletin published by the People’s Health Movement and Peoples Dispatch. For more articles and subscription to People’s Health Dispatch, click here.