On October 15, the government of Uganda introduced a 21-day curfew in an attempt to curb the recent Ebola outbreak. The outbreak, caused by the Sudan strain of the virus, remains a huge global concern. Health workers and patients in Uganda also remain especially worried, as the number of deaths continues to rise.

Just weeks before, President Yoweri Museveni had claimed that the outbreak was under control and that there was no need for panic. But the state of the health system, burdened by the pressures of COVID-19, has cast doubts on his assurances. The health system in Uganda urgently needs refurbishments of essential personal protective equipment (PPE) and solidarity from other countries in Africa and the rest of the world.

The outbreak was declared on September 20 by the Ministry of Health, based on tests carried out on a patient from Ngabano village, Mubende District, in Central Uganda. It is the first outbreak of the Sudan strain in Uganda since 2012. As of October 20, 64 cases had been confirmed in the country according to the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Africa.

Cases were first detected among people living around a gold mine. Gold traders are highly mobile, particularly along the busy highway that runs between Kampala — a densely populated and globally-connected capital of 1.68 million people — and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This raised concerns about the virus’s ability to spread easily to densely populated areas, which would increase the number of reported cases and, likely, deaths.

It has been clear from the very beginning of the outbreak that the uneven distribution of resources within the health system, as well as its overall status, would impact the Ugandan response. For example, because diagnostic resources were not readily available in Mubende, tests were done 173 kilometers away at the Virus Research Institute in Entebbe, and so it took two days for test results to be available. This meant that more people could have been exposed while results were awaited.

There is no known vaccine for the prevention of the Sudan strain of Ebola, and no known treatment for it. Like all other Ebola strains, it is a serious disease with significant morbidity and mortality. Because it is spread through body fluids, it is not as easily transmissible as airborne viruses such as COVID-19. Still, it puts healthcare workers and family members of patients at significant risk.

Health workers at risk because of lack of PPE, staff shortages

Since there are no approved vaccines or treatments for this Ebola strain, part of the response to the crisis depends on using protective equipment and following hygiene guidelines. This is true among health workers as much as among the general population. The WHO has confirmed 25 deaths, five of which have been of health workers. Local reports indicate that at least seven health workers have contracted Ebola and dozens of health workers have been identified as contacts of the victims.

The deaths of health workers have raised questions about the ability of the health system, the government, and health facility management to protect essential workers from harm. Ministry officials have blamed infections among health workers on low vigilance, while other medical superiors say workers have not been provided with appropriate PPE.

Senior health officials, including Dr. Asaph Owamukama and Dr Samuel Oledo, president of the Ugandan Medical Association, warned that the need for PPE was growing by the day because of the outbreak. In a conversation with The Monitor, Owamukama and Oledo agreed that in any situation where Ebola is a possible diagnosis, health workers should be covered head to toe. “Ebola is not a joke,” Oledo stressed in the interview.

This does not only refer to health workers in hospitals, but also to Village Health Teams (VHTs). According to statements made by Minister of Health Jane Ruth Aceng, one of the main tasks of the VHTs is to remain vigilant when it comes to unexplained health events in their areas. In this case, it seems that the teams faced delays in recognizing the seriousness of the situation in Mubende. Yet, the minister recognized that the government does not pay VHT’s salaries and this likely impacts their ability to perform the work they have to do.

It should also not be ignored that Uganda is facing an overall shortage of workers. Not having enough nurses and physicians in the health system might have meant that cases of Ebola went unreported for weeks. This opinion was shared by the WHO Regional Director for Africa, Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, at the World Health Summit in Berlin. Moeti used this as an example of why the world should make it a priority to employ more health workers, ensuring that the capacity exists to react to outbreaks of communicable diseases.

Solidarity should prevail over securitization of health

Employing more health workers in Uganda is a necessity, yet it is not easy to achieve within the current financial and health framework. At the same time that it is managing this Ebola outbreak, Uganda is also facing a resurgence of malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV, as well as the burden of COVID-19. All this while relying on far fewer resources than countries in the West: 30% of Ugandans lived on less than USD $1.77 per person a day in 2020.

Health minister Aceng also called on other countries to donate essential equipment such as medical gowns, gloves, masks, face shields, surgical hoods, and long boot coverings to Uganda. In her statements, she made it clear that Uganda could not face the Ebola outbreak alone and that, if it was forced to do so, the risk of the disease spreading to neighboring countries would only grow.

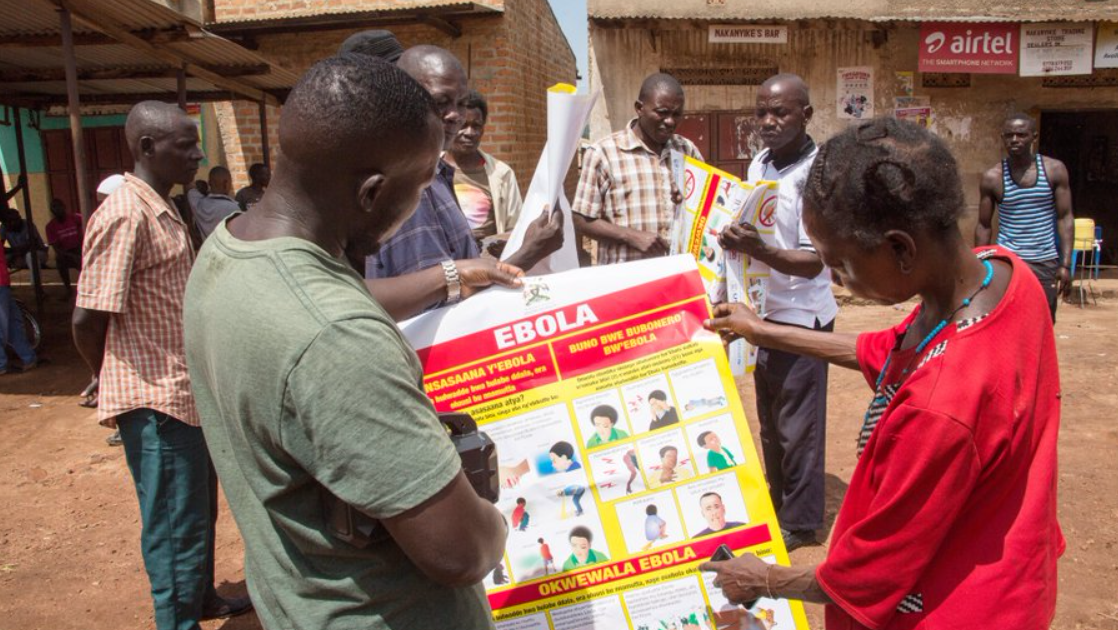

Ugandan activists, including those from the People’s Health Movement, as well as the minister of health and public health officials, have launched requests for solidarity, but these have been met with silence by leaders across the world. Instead, other countries have already begun implementing stricter security measures.

The United States has started screening travelers from Uganda at five airports, and is monitoring them for 21 days to see whether symptoms develop. Neighboring countries like Kenya and Tanzania are also on high alert.

Ebola has always made global headlines, regardless of strain or country of origin, but it tends to disappear from the minds and imaginations of the West once the direct threat to high-income countries subsides. This has been true for all outbreaks until now and there is no evidence that this time will be any different.

Instead, what is needed is a response that is completely different from what has been experienced in the past. At this point in time, the Ugandan people and health workers need the solidarity and the support of high-income countries. These can come in the form of the donation of equipment, but also require the provision of due attention to research into Ebola as well as the development of vaccines. Failing that, future outbreaks will continue to cause unnecessary deaths in Uganda and other countries in Africa, as well as threaten the health of people in the rest of the world.

People’s Health Dispatch is a fortnightly bulletin published by the People’s Health Movement and Peoples Dispatch. For more articles and subscription to People’s Health Dispatch, click here.