On March 21, over 350 people, the majority of whom were women, graduated from the Second Phase of the Fred M’membe Literacy and Agroecology Campaign Program. Officially launched in 2021, the program is the product of a collaboration between the Socialist Party (SP) of Zambia and the Samora Machel Internationalist Brigade of Brazil’s Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST).

In the years since, the literacy program has been implemented in both rural and urban areas, teaching over 4,000 workers, women, and otherwise marginalized groups to read, write and speak in English—the country’s official language.

“For the first time I have been to a room in this country, to a hall in this country where everyone can read and write. This is a liberated zone today,” SP President, Dr. Fred M’membe, stated during the graduation ceremony.

According to Zambia’s 2018 Demographic and Health Survey, one-third of women and 18% of men in the country were illiterate, which meant that they could not read at all.

In the country’s Lusaka, Eastern and Western provinces, where the literacy program was first launched, 19.9%, 50%, and 36.7% of women between 15 and 49 years of age, respectively could not read at all. The overall gap between urban and rural areas was similarly stark, at 19.4% against 45.8% illiteracy.

Only 6% of women and 8% of men surveyed had obtained higher education, according to the DHS survey. Access to secondary and higher education was significantly determined by wealth, with only 1% of women and 3% of men in the country’s lowest wealth quintile having completed their education at these levels.

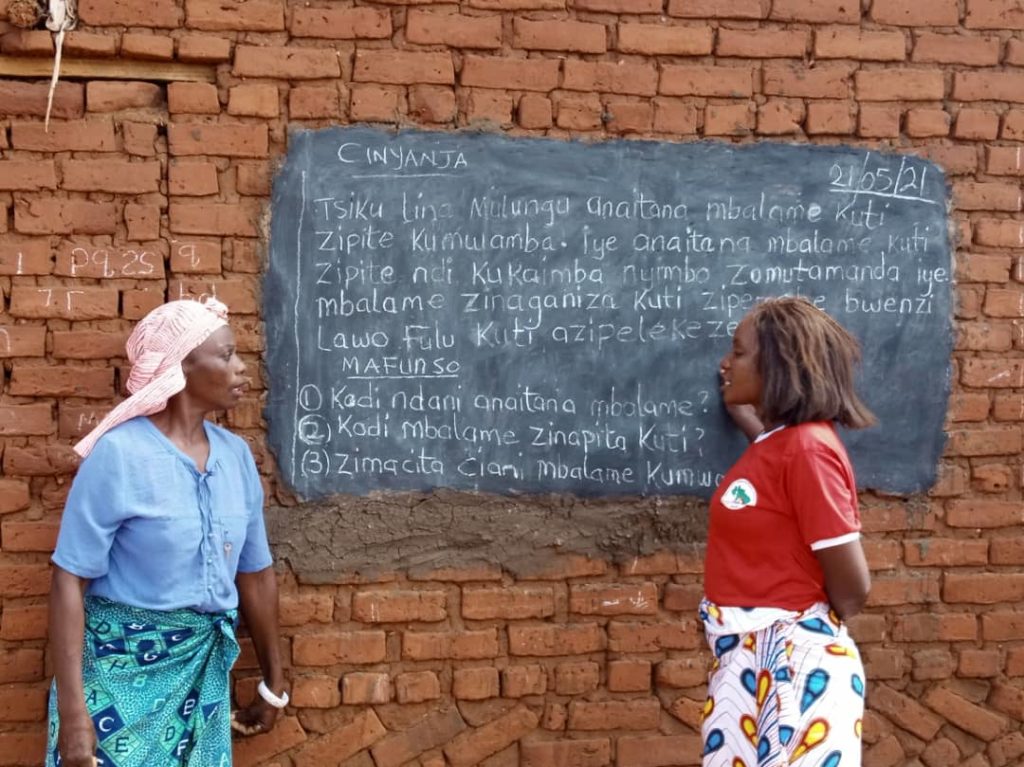

It is against this backdrop that the adult literacy campaign was first mobilized in 2019, and subsequently carried out across 22 municipalities, in primarily rural communities starting in 2021.

“The ability to read, to write, to express oneself, is critical for emancipation. This is especially so for women who have, for a long time, been marginalized out of political processes and the economic sector, and education in general. The literacy program is core in ensuring gender equity, and ensuring that poor people are empowered,” Cosmas Musumali, the General Secretary of the SP, told Peoples Dispatch.

While Zambia has over 70 Indigenous languages in which people are multilingual, and even literate, the emphasis of literacy in English stemmed from the fact that it was incorporated into “all areas of political, social, and cultural life” in the country, and as such, deemed necessary for people to be able to access basic services, including education and healthcare.

“Education is an equalizer… [However] in Zambia, we have a system that pushes people into education based on money, and poor people fall out of the system,” Musumali said. While Zambia had implemented free education under former President Kenneth Kaunda, the country implemented user fees and other neoliberal reforms with the beginning of Structural Adjustment in the early 1990s.

The current government of President Hakainde Hichilema has implemented free education at the primary and secondary levels, even as the government has struggled with austerity policies amid a severe debt crisis since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For those who have been left out of the education system, “as adults, they are critically disadvantaged as they are unable to read or write. Generally, in a country which has English as its official language, people are then made dysfunctional in so many ways. Jobs require some level of literacy and ability to speak English… It becomes almost an impossible task for people to be empowered, to be able to support their families,” Musumali said.

“The SP took it upon itself to experiment with certain ideas, to determine how we could quickly empower our people, for them to be able to read and write. We believe that any revolutionary change is only possible if it is carried out by the people, they must be conscious and self-organizing. Education is a critical pillar of any socialist transformation.”

Education for liberation

The development of the program in Zambia was informed by the “Yo, sí puedo” (Yes, I Can!) adult literacy method developed by Cuban educator Dr. Leonela Relys Díaz in 2001, and informed by the ideas of revolutionary leader Fidel Castro. The method has helped over 10 million people across 30 countries become literate, also playing an important role in the Bolivarian Revolution under the leadership of Hugo Chàvez in Venezuela.

The “to talk, to read, to write the words in the world” method that has been implemented in Zambia is based on the idea of popular education, as advanced by Brazilian educator and philosopher Paolo Freire, and other methods that find their origins in Latin America.

While the first phase of the literacy program was focused on rural communities, the second phase expanded to urban areas in Lusaka.

Importantly, the focus of the program is not just on literacy but agroecology, in a context where 1.5 million smallholder farmers produce 90% of the country’s food, and farming families are acutely vulnerable to climate shocks, including a severe drought at the moment which the Zambian government has officially declared a “national disaster”.

Including agroecology presented “an opportunity to harmonize the struggles against the injustices inflicted on the poor by capitalism and its local agents, we sadly learn that the communities most affected by illiteracy are dominated by peasants who, in our opinion, deserve the attention of both literacy and agroecology,” said, Graster Mundi from the SP’s agroecology front, speaking to the Samora Machel Internationalist Brigade in 2021.

As part of this initiative, the MST also provided seeds from Brazil for Zambian farmers to plant and grow.

International solidarity across borders has been key. “We live in a globalized world, it works for capitalism as it builds networks across continents. The class struggle is also global, and building connections becomes much more important for our socialist process.”

“In Zambia, we are dealing with people who have huge needs in terms of their emancipation, our resources are few but our ability to organize and to learn from each other becomes a centerpiece of international solidarity. We do not have to reinvent the wheel, we know that the Cubans faced a similar problem at the beginning of their Revolution and they determined a way to eradicate illiteracy in a short period of time,” Musumali said.

“On the African continent, revolutionary leader Amilcar Cabral and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAGIC) took up concepts developed in Cuba which helped improve the literacy program developed in Guinea-Bissau. In Brazil, the MST did the same. We have learned from all this and come up with a program that is best suited for the Zambian context… It is a process of collective learning.”

This collective learning has also taken place within the program, between the teaching volunteers and the participants. “It is not a one-sided process, our trainers have stated that they have learnt more from the participants and from the methodology. Empowerment goes both ways.”

The literacy program has also integrated popular health and communication. Learning to read and write must make a material difference in the conditions of people’s lives, Musumali said, especially when it comes to literacy programs for adults.

“We have peasant farmers, the majority of whom are women. They have to understand agroecology, how they can grow crops and sustain their families. Fertilizers and seeds constitute the highest costs in agriculture in Zambia—so to be able to do it in a way that is environmentally sustainable, that enhances life, and produces food that is nutritious is critical.”

The literacy program has also aimed at improving routine health interventions, at both the community and household levels. For instance, in January, the MST and SP organized a Popular Health Clinic to provide information and assistance in the midst of a cholera outbreak in the country.

For the SP, the initiative has also aided in the advancement of a political project for Zambia, “we understand the difficulties of illiteracy much better, it has primed us to come up with better policies to reprioritize investments that are going into education. A literacy program is not just about learning for a small group of people, it has a multiplier effect in society— just the fact that parents are now able to assist their children in education.”

The SP is now at the stage of assessing the first and second phases of the program and looking at ways to expand it further in a third phase.

“We are building huge resilience in society, it goes beyond the immediate outcomes of the literacy program. The political process has to be driven by the needs of the people—for people to be able to read and write, to have a certain level of health, these are key pillars upon which our socialist process will rest,” Musumali said.

Speaking at the graduation ceremony in Lusaka, Kyeretwie Opoku, the convenor of the Socialist Movement of Ghana (SMG), also emphasized that the work of the SP and MST to facilitate literacy was taking place not through an NGO or a donor program, but in the “context of political struggle.”