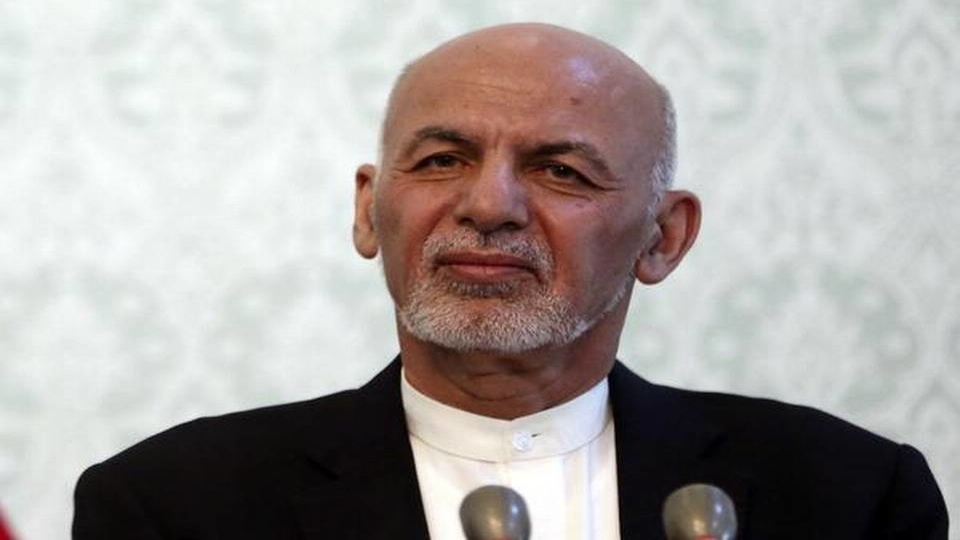

Ashraf Ghani may have been declared the winner of the September 28 presidential elections in Afghanistan but the possibility of a run-off election looms large. According to the preliminary results announced by the Independent Election Commission of Afghanistan (IECA) on Sunday, December 22, Ashraf Ghani got 50.64% of the votes while his main rival Abdullah Abdullah obtained 39.52%.

After the publication of the results, thousands of complaints of fraud and technical glitches in the biometric identification process (which was introduced in this election) were filled by opposition candidates and parties. Abdullah Abdullah and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who came third with just 3.85% of the votes, said they would formally challenge the results.

According to the electoral law in Afghanistan, candidates can challenge the results within three days of its publication. The final results can only be announced after those challenges are disposed of. It is speculated that a review of the results will see Ashraf Ghani’s vote share come down to below the 50% mark. This will necessitate a run-off between the two leading candidates. Reuters quoted Deen Mohammad Azimi, deputy head of the IECA, saying that “looking at the scope of complaints and objections that needs a thorough review, there could be a run-off”.

According to TOLO news, the IECA said it may take at least 39 working days to evaluate all the complaints. Since the term of Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah ended in May this year, other candidates had demanded a caretaker government before the elections. They reiterated their demand after it was clear on December 23 that the final results may take some more weeks. They demanded a “national participation government”. This has been rejected by the office of Ashraf Ghani.

The elections were originally scheduled for April 2019. However, due to the lack of preparation and ongoing problems with the results of the local body elections held a few months before, the IECA chose to delay it till September 28. Voting was finally held amid widespread violence and boycott calls given by the Taliban which controls more than 20% of the country. The Taliban has refused to recognize governments and electoral processes in Afghanistan, calling them products of occupation and hence, illegitimate. This is despite the fact that it has been involved in formal negotiations with the US for more than a year now.

Amid the violence, only 1.82 million out of the total 9.6 million registered voters came out to vote on September 28. This was around 20% of the total registered voters. Afghanistan has a population of more than 35 million. The 2014 presidential election saw a voter turnout of around 60%.

Complaints of electoral fraud are common in Afghanistan. Abdullah Abdullah had challenged the results in 2014 as well. He was made chief executive of the country under Ashraf Ghani’s presidentcy as part of a compromise formula suggested by the United States.

Abdullah Abdullah had made it clear before the announcement of the preliminary results that he would not accept it until votes from 27 out of the 34 provinces were recounted. According to him, the IECA counted the votes in these provinces without the presence of his agents. His and Hekmatyar’s supporters tried to stop the counting at several places for months. All these resulted in the delay in the results which were earlier scheduled to be announced on October 19.

Ashraf Ghani, however, is reportedly reluctant to compromise this time and has appealed to his rivals to accept the results. It is most likely that the US may intervene in case the candidates are not able to arrive at an agreement. The Twitter handle of State Department’s South and Central Asian Affairs section issued a statement in which it asked the IECA to “adjudicate any complaints in a professional and transparent manner.” It also added that since the majority of Afghans were not able to vote, whoever wins the elections should ensure that “country’s rich diversity is well reflected in its leadership”.

The dependence of the country’s ruling elite on the US reflects its failure to come out of the shadow of the imperial power which has maintained control since its invasion in 2001. It is also clear that the so-called democratic process in the country that began during the US-led NATO occupation has failed to win much popular support. The rising threat of the Taliban and the complete inability of the government in Kabul to implement any policy or law outside its pockets of influence further de-legitimizes the rag-tag system created by the occupation forces. People see most of the political parties and their leadership, which mostly comprises current or former warlords, as corrupt, which makes a majority of them uninterested in and cynical about the electoral process.