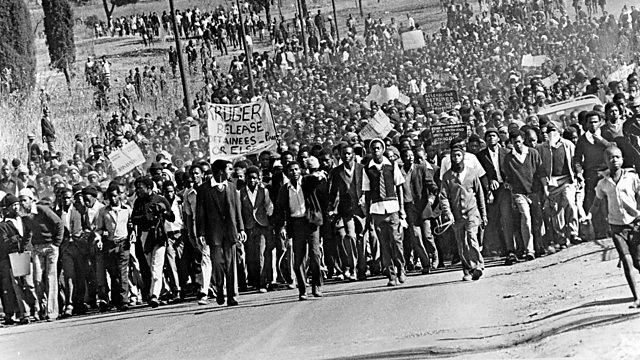

June 16 commemorates the gallant and courageous struggles of students against the imposition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction to further culturally subjugate Africans. What started as a peaceful demonstration resulted in a massacre where the apartheid regime unleashed the might of the state on unarmed students.

Today, a celebratory and commemorative mood consisting of special events and speeches pacify the class character of the memory of South Africa’s 1976 Soweto Uprising. This erases its combative history and the defining role it played in the struggle against the white supremacist apartheid regime.

The massacre of defenseless students on June 16 sparked the abhorrence of the international community against the regime’s violence. One key moment was Sam Nzima’s photograph of Hector Pieterson in the arms of Mbuyisa Makhubo. For the defiant youth of South Africa, the violence inflicted during the days of the uprising exposed, to them and the world, the ruthless and merciless lengths at which the apartheid forces were prepared to go to maintain a system of domination and exploitation.

Fundamental questions were asked: Why do we have inferior education facilities? Why are we overcrowded in schools? Why do we have teachers who are incapacitated? Students were questioning the “baaskap” mentality of apartheid, the system of white domination and the entire economic system upon which it was based. It manifested itself in almost every aspect of life, most evidently through the forceful use of Afrikaans as the language of instruction.

These questions continue to be relevant today. In 2015 multiple protests arose under the banner of #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall. Students were demanding that access to education must be free, quality, decolonized and de-commodified.

Education for exploitation

In 1953, the Bantu Education Act was passed. Bantu education existed amongst a battery of racist laws used to power the engine of apartheid. Its objective was to provide a racially segregated education system which existed to maintain the economic base of South African society. In his book House of Bondage, the photographer Ernest Cole accurately described this as “Education for Servitude”. Its main function was to feed and fortify the economic base that sustained a racist political economy through the super exploitation of cheap, black and African labor.

From Soweto in Johannesburg to Langa in Cape Town, thousands of students took to the streets. The strength in their mobilization and decisive action did not only lie in confronting the unilateral decision of Afrikaans as the medium of instruction in schools. Rather, through highlighting the class contradictions in education – with annual expenditure measured at R42 spent on a black learner versus R644 on a white learner – students unmasked the apartheid system as the face of capitalism.

Reigniting the movement

The thirst and burning desire for freedom of the June 16 movement spread a revolutionary energy across the nation. Young people crossed borders and joined the liberation movements in exile. Others swelled the ranks and boosted the morale of South Africa’s trade union movement. Triggering a far deeper consequence, the ripple effects of the uprising fast tracked the recruitment of young people into organizations that sought to fundamentally destroy the apartheid system. These include Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) and the Azanian People’s Liberation Army (APLA) – both banned organizations at this point in time.

Considering that the strategic objective of these organizations was to destroy the brutal apartheid system by any means necessary, the Soweto Uprising should be recognized as the spark that triggered the swelling of their ranks.

Sung by soldiers into exile, Sobashiy’ abazali ekhaya marched to the beat of boots worn by freedom fighters throughout Sub Saharan Africa. Popularized after the series of demonstrations known throughout the world as the Soweto Uprising, the song brings to life the totalizing sacrifice and ultimate price paid by young gallant militants:

Sobashiy’ abazali ekhaya (We left our parents at home)

Saphuma sangena kwamany’ amazwe (We left and entered into other countries)

Lapho kungasekho umama nobaba (Where our parents are no longer around)

Sikhangel’inkululeko (In search for freedom)

Sithi sala sala salan’ ekhaya (Stay well at home)

Sesingena kwamany’amazwe (We are entering other countries)

Lapho kungasekho umama nobaba (Where our parents are no longer around)

Sikhangel’inkululeko (In search for freedom)

Sobashiy’abafobethu (We left our brothers)

Saphuma sangena kwamanye amazwe (We left and entered into other countries)

Lapho kungasekho umama nobaba (Where our parents are no longer around)

Sikhangel’inkululeko (In search for freedom)

From South Africa to Mozambique, Zambia, Angola and beyond, its rhythm manifested as a rallying cry that became synonymous with the struggle against Apartheid: South Africa’s racist face for capitalism.

Broadening and building alliances throughout the continent was central to the struggle against apartheid plunder and its doctrine of racism. The exchange of revolutionary ideas, language and culture laid broad the political landscape of the young cadres. Comrades learned to speak Swahili and shared revolutionary literature.

June 1976 intensified and gave birth to a political program in a moment when the reign of terror in South Africa resulted in a lull after liberation movements had been banned and expelled. In a long list of young people who rose out of the June 16 movement, the brave and very young Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu started his journey in Mozambique and was ultimately trained at the Engineering camp in Angola. In acknowledging his selflessness and dedication to the struggle, the already existing African National Congress (ANC) education center in Tanzania, was renamed to Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College, after he was hanged by the apartheid state. This is where new recruits were trained in political education. It was to serve as an alternative to the inferior Bantu Education system at home in South Africa.

An injury to one is an injury to all

The struggle against apartheid was not only for the South African working class struggle alone, as the advancement of revolutionary action against the repressive might of the evil apartheid forces would have a ripple effect on the domination of African people in the broader region. Progressive leaders of the former colonies on the continent of Africa who had attained independence (such as Mwalimu Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, Samora Machel in Mozambique, Agostino Neto in Angola and Kenneth Kaunda in Zambia) knew this and opened their doors to South African exiles. This allowed the South African liberation movements to consolidate themselves and organize their strategies and tactics for more decisive combat. It was informed by a concrete program of international solidarity, based on supporting the material and political life of a people in need.

The June 16 movement was a definitive advance of the struggle against apartheid and continues to be a revolutionary reference point for the youth today. From Kinshasa to Johannesburg, the battle for education as a public good is a war the working class still needs to win! We will not realize this until we arrest the exploitative and oppressive capitalist and imperialist system and usher in socialism.