Days after yet another round of raids on activists in the Central Luzon region, labor movements in the Philippines have demanded that the government and the judiciary prevent such atrocities. In a virtual seminar held on March 31, Wednesday, labor organizations from across the Philippines came together to recount the repression their members have suffered over the years under the Rodrigo Duterte government, and called for an end to the bloodshed.

Groups such as Kilusang Mayo Uno or the May First Labor Movement, have pointed out that the raids are taking place in the export processing belt in northern Philippines, where trade unions are a strong political bloc. Along with KMU, the left-wing coalition Bayan Muna has also exhorted the courts to be more discerning with the arrest warrants that they pass, hinting that “they are being used by the Duterte administration to crack down on activists.”

A statement released by the Nagkakaisa Labour Coalition president Sonny Matula also echoed the same demands, calling on the government to “concretize the provision of the Constitution to protect the workers.”

Several trade unions and church-based organizations have called for an end to red-tagging, violent raids and a serious commitment from the government to end the crackdown on activists.

Earlier this week, on March 30, two labor activists were arrested in simultaneous raids on trade union offices in Luzon, by the Philippines National Police. The two arrested activists are KMU vice-chairperson for Central Luzon, Florence “Pol” Viuya, and Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas vice-chairperson, Joseph Canlas.

Meanwhile, the office of labor activist Marites Santos David of Alyansa ng Manggagawa sa Engklabo (AMEN) was raided on the same day in his absence. Of these, Viuya has been charged with possession of firearms and explosives, which the KMU alleged was planted to scuttle the chances of bail. Canlas was released later on bail, and David was declared “at-large” even though the police only procured a search warrant against him and no arrest warrant to implicate him as a fugitive.

The raids come just weeks after similar raids in Calabarzon led to the death of nine activists and arrest of six others, in what came to be known as the Bloody Sunday, and the killing of a KMU activist, Dandy Miguel, by unidentified assailants in Laguna.

These raids have become highly controversial for the tendency of the police to violate established legal procedure, something that was admitted to the UNHRC by the Department of Justice, allegations of planted evidence to prevent bails, blanket warrants and copy-paste warrants passed by lower courts against activists, which were used in the Bloody Sunday raids, and extremely high chances of police killings.

At the same time, the assassination of grassroots activists is also becoming commonplace in the Philippines, like that of Dandy Miguel, whose murder sparked so much backlash that it pushed the Department of Justice to initiate an investigation.

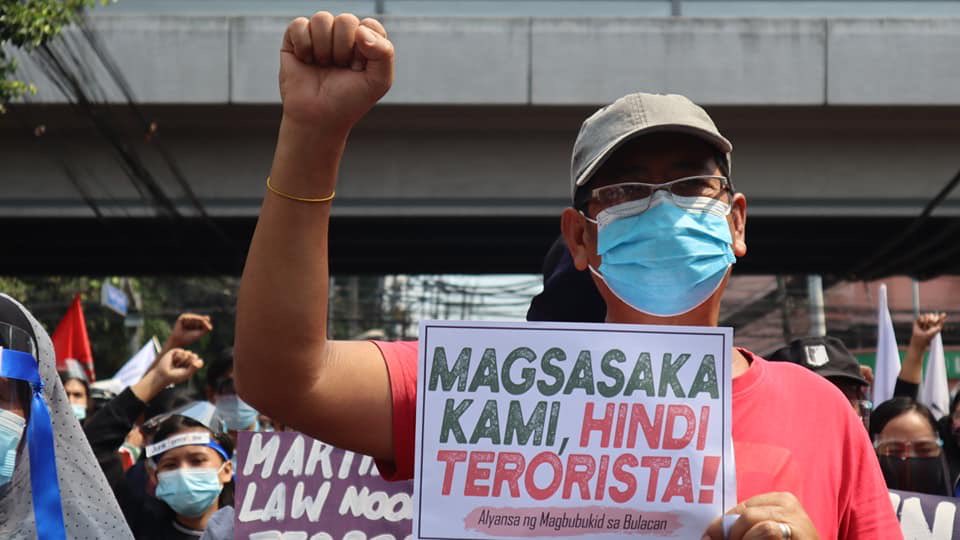

Cases of red-tagging – accusing groups and individuals of being associated with the banned Communist Party of the Philippines and armed groups, especially by government agencies including the military, the police and the anti-insurgency agency National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) – have been on the rise. This has made activists more susceptible to violent police raids or assassinations by pro-government groups. For instance, both Dandy Miguel and Marites Santos David were red-tagged by authorities as being associated with CPP’s mass fronts, without any evidence.

Earlier this month, an opposition senator Franklin Drilon tabled a bill in the Senate which will seek to make red-tagging a punishable offence. The bill titled Act Defining and Penalizing Red-tagging (Senate Bill No: 2121), will make red-tagging a crime punishable by up to 10 years in prison. The bill has whipped up a storm after social movements and church leaders have extended support for a law that will put an end to the practice, that has implicated a host of institutions, from universities to church charities, of being fronts of the communists insurgents.