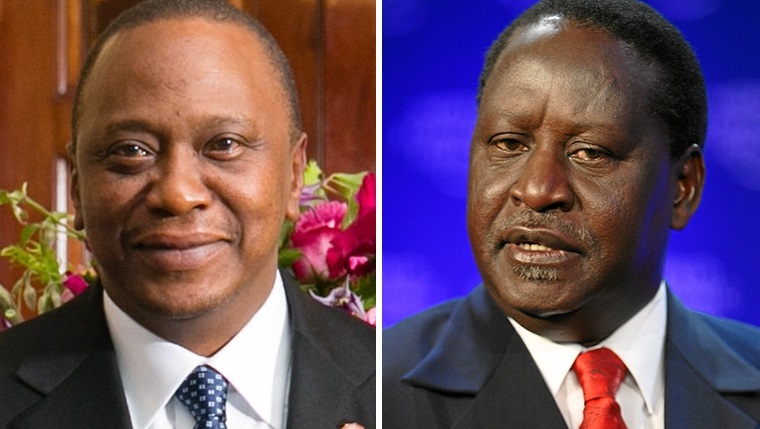

The Communist Party of Kenya (CPK) will hold demonstrations on July 7 in the capital city Nairobi to reject the sweeping constitutional reforms introduced by the government of Uhuru Kenyatta. Critics say the amendment will cement a power-sharing arrangement between president Uhuru Kenyatta and the country’s main opposition leader, Raila Odinga, ahead of the upcoming election in 2022.

The Nairobi High Court, on May 13, had struck down the Constitutional Amendment Bill, 2020, as illegal, only months before it was scheduled to be placed before the public for a referendum. On June 30, the Appeals Court is scheduled to respond to the government’s application challenging the High Court order. The wide-ranging amendments seek to alter the very basic structure of the constitution and would have affected 13 of 18 chapters.

One of the amendments seeks to introduce the prime minister’s post, ostensibly to reduce the concentration of powers in the hands of the president. However, the widespread perception is that this is merely to allow Kenyatta and Odinga to share between themselves the posts of president and prime minister after contesting as allies in the 2022 election, making a mockery of political choice.

This judgement, which has thrown a spanner in the works of Kenyatta and Odinga, has received much praise for its people-centric — rather than state-centric — interpretation of the 2010 constitution, which was a milestone in Kenya’s struggle for political and civil liberties. However, the judges who wrote it are facing the wrath of a retributive president.

Two of the five high court judges on the bench which delivered this judgement were slated for promotion to the supreme court. Their names, along with those of others, were proposed by the judicial service commission. However, on June 7, Kenyatta refused to sign off on it and the promotions of a total of 41 judges have been withheld.

There is no precedent to such actions by the president to antagonize the judiciary, CPK’s National Vice-Chairperson, Booker Ngesa Omole, told Peoples Dispatch.

A week earlier, on June 1, the Madaraka Day which commemorates the attainment of internal self rule in 1963, president Kenyatta issued thinly veiled threats to the judiciary in his speech. The judiciary, he said, has been testing “our constitutional limits” since 2017 when it nullified the result of the presidential election.

Breaking protocol as per which the president of Burundi, who was the dignitary, was to speak before the leader of the opposition, Kenyatta instead invited Odinga to speak ahead of his turn. Odinga reiterated his continued support for Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) of which the constitutional amendments are a central plank.

Incidentally, Odinga had challenged the result of the election in 2017 in court, when he was a bitter enemy of Kenyatta. Soon after Kenyatta was declared as the victor on August 8, Odinga ordered his militias to go on a rampage, Omole recollected. With a trigger-happy police, violence escalated, and the blood-letting did not stop for a week, until the court nullified the election after finding wide-spread fraud and malpractice.

By law, the elected government under such circumstances remains in office for 90 days, within which the election commission must organize a re-election. When it did, Odinga boycotted the election. Kenyatta, in order to maintain the optics for competition, “created some opponents to compete against him,” Omole said.

Having won this election with a voter-turnout of less than 50%, Kenyatta was staring at a loss of legitimacy. In many areas that are regarded as Odinga’s strongholds, the boycott of the election was near total. Amid this crisis, Kenyatta became increasingly paranoid about the divided loyalties of the MPs from his Jubilee Party between himself and his vice-president William Ruto.

“Ruto is seen as an outsider who is not a part of the big families which take turns ruling Kenya,” Omole said, explaining his unacceptability to the ruling elite, despite having banded closely with Kenyatta since 2013, when both were accused of engineering the post-electoral violence in 2007. So Kenyatta instead reached out to his arch-rival and leader of opposition, Odinga, who heads the Orange Democratic Party (ODP).

The negotiations between the two culminated into the infamous “handshake” in March 2018, which left the cadres of both parties — who had been mobilized to draw blood of opponents less than a year ago — confused and disoriented.

As a part of the compromise, some bureaucratic and diplomatic appointments were made to the liking of Odinga. But a more crucial part of the agreement was the BBI — ostensibly a national dialogue to heal a polity torn by frequent electoral violence and arrive at a means to address its root causes.

Most members of the presidential task force — appointed to prepare the BBI report where these sweeping amendments to the 2010 constitution were proposed — were chosen by Odinga. The report, instead of holding accountable political leaders like Odinga responsible for the electoral violence, admonishes “leaders and citizens alike” for having “a noticeable and destructive inclination to disrespect the law.”

The solution it offers to divisive elections includes the introduction of the post of prime minister, who will be chosen by the president from among the MPs of the party which has majority seats and can be dismissed at his will.

This, far from addressing any of the issues at the root of political violence, only facilitates a power-sharing arrangement between Kenyatta and Odinga, Omole said. Such power sharing arrangement raises questions regarding the very purpose of elections.

The report in any case announces in the very opening paragraphs of the executive summary that “Kenyans are tired of elections that bring the economy to a standstill every few years and feel that politics has become too adversarial.”

Should the amendments have gone through, he maintains, the 2022 election would have been a mere mock drill. However, the judgement declaring the amendments illegal has thwarted that possibility.

“Even if the government now manages to strong arm the judiciary into letting the referendum on the amendments take place,” Omole is confident that “the people will vote against it in the referendum.”

An understanding is now widespread in the Kenyan society that the BBI is an attack on the 2010 constitution, for which much sacrifice was made in struggle by the progressive political forces in Kenya. The contempt of the political elite for this constitution which recognized the political and civil rights of Kenyans, Omole said, is evident in the report’s claim that “we have placed too much emphasis on what the nation can do for each of us — our rights — and given almost no attention to what we each must do for our nation: our responsibilities.”

It is against this opportunistic alliance that CPK members and civil society plan to gather below the statue of freedom fighter Dedan Kimathi in the city center and march to Kibera courts on July 7, the “Day of Resistance.”