The International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances is marked every year on August 30. This year, Bangladesh was one of the countries where families of victims and organizations working in the area demanded clear answers from the government.

Several rights organizations, including Odhikar, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and Mayer Daak, have called upon the United Nations (UN) to lead an impartial investigation into cases of enforced disappearances in Bangladesh. In a joint statement, the groups called for Bangladeshi security agencies to be held accountable for allegedly subjecting hundreds of people to enforced disappearances in the country.

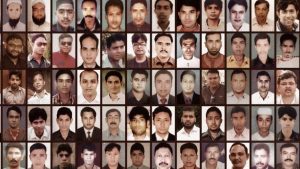

As many as 600 people, including opposition leaders, activists, journalists, businessmen, and others, have been subjected to enforced disappearance since prime minister Sheikh Hasina took office in 2009, according to the rights groups.

Dhaka-based rights organization Odhikar documented cases of disappeared people between January to April this year. Its report stated that “at least 11 people have gone missing after they were mysteriously picked up by some unidentified men.”

“From April to June 2021, a total of five persons were allegedly disappeared after being picked up by men claiming to be or dressed as members of law enforcement agencies. Among them, one disappeared person was shown as arrested after a few days of disappearance and the whereabouts of the other four remain unknown,” Odhikar said in its three-month report.

As per several activists and critics, enforced disappearances have continued unabated during the COVID-19 period in Bangladesh. Rights groups also note that more recently, some of the disappeared persons have resurfaced in government’s custody after being arrested under the draconian Digital Security Act 2018. The rights groups claim that the government is “assaulting dissenting voices that are critical of the government’s repressive policies.”

A decade of disappearances

A detailed report by the Human Rights Watch (HRW) in August verified 86 enforced disappearance cases over the last decade where the victims’ whereabouts remain unknown.

Based on over 115 interviews with victims, family members, and witnesses of enforced disappearances, the 57-page report titled “Where no sun enters: A decade of Disappearances in Bangladesh” states that the Sheikh Hasina-led government authorities “have arrested hundreds of Bangladeshis including children” for criticizing the government on social media. “Most of these arrests are under the Digital Security Act, a vague law passed in 2018 granting law enforcement the powers to arrest anyone accused of posting information,” the report says.

Odhikar claims that between April to June, at least 50 people were arrested under the Digital Security Act for making critical posts against prime minister Hasina and her family, other ministers in her cabinet, and Indian prime minister Narendra Modi.

Other Dhaka-based rights organizations including Mayer Daak (Mother’s Call) and the Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances have reported a rise in extrajudicial killings allegedly committed by the security forces in Bangladesh. The number reportedly rose from 70 cases in 2012 to 329 cases in 2014 under the rule of Hasina’s Awami League.

“At least 98 people were reportedly forcibly disappeared in 2018,” according to Amnesty International. In 2019, Amnesty noted that victims are first subjected to enforced disappearance before being formally arrested or charged, which lasts from a day to over a month.

Abuse by security forces

Over half of the 86 persons profiled in the HRW report were first picked by the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB). The RAB was created in 2003 to tackle drug smuggling, crime, and regulating internal security of Bangladesh. The notorious unit is often called by rights organizations as the “death squad”. Over the years, the battalion has been repeatedly accused of human rights violations and conducting enforced disappearances. Several groups have called for the unit to be disbanded.

The RAB has a dubious record of dragging people from homes or vehicles in the middle of busy intersections in front of witnesses. Its members have often identified themselves as being from “the administration”.

In 2017, a Bangladesh court sentenced 26 people, including 16 members of the RAB, to death for their role in killing seven people including former councilor Nazrul Islam in Narayanganj city in April 2014. The court sentence was a rare example of RAB officials being penalized for their actions.

According to the HRW report, prime minister Hasina has persistently denied any responsibility for the enforced disappearances taking place under her regime. The rights groups stated that “refusal to credibly investigate the fate and whereabouts of the disappeared person amounts to abdication of responsibility.”

Abduction and denial

On March 9 last year, a criminal defamation complaint was filed by a member of parliament from the ruling Awami League against journalist Shafiqul Kajol for his social media post. A day later, the journalist went mysteriously missing. This sent a chilling message to the journalist fraternity. After 53 days, Kajol was reportedly “found blindfolded, with his legs and arms bound” in a field by border guards in Benapole, a town near the Indian border.

In a similar case in December 2013, Sajedul Islam Shumon, a well-known leader of the Bangladesh National Party, was allegedly picked up by members of the RAB, along with seven other people. His family confirmed that senior officers of the RAB had informally accepted that he had been picked up, but his whereabouts remain unknown.

“Whenever we go to law enforcers for any update, they just tell us that they are looking into it,” said Shumon’s sister Firdouse Rehman during one of the sit-in protests against his enforced disappearance at the Jatiya Press Club. “We just want to see his body or his grave so that we can at least pray for him there,” she said.

In March 2014, Mahabubur Rahman Ripon, an opposition activist against whom the present dispensation had lodged several cases, was in his house when a group of unidentified men in plainclothes dragged him in the middle of night, claiming that they belonged to the RAB.

Ripon continues to remain missing, even as his family has been moving from pillar to post in search of him, filing several police complaints but to no avail.

Bangladesh in South Asia is a member of the United Nations Human Rights Council. However, its law enforcement agencies face several allegations of human rights abuses by rights organizations. Government agencies are accused of having “extorted money from people by threatening to kill in crossfire; shooting in the legs; arresting and imprisoning innocents other than the main accused,” states the Odhikar report. They were also responsible for “torture and death due to torture in police custody,” Odikhar stated.

These enforced disappearances have created fear and apprehension in the country as the “tendency of law enforcement agencies to deny detention has become a dangerous trend.”

Meanwhile, security agencies have denied any involvement in the abductions of people whose whereabouts remain untraced. Rights groups stated that “the obstinate denial of the government and its refusal to disclose the fate and whereabouts of the disappeared persons indicate its unwillingness to address this serious issue.”

Bangladesh authorities have even denied several cases transmitted by the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID), and barred visits by UN special representatives and the WGEID on many occasions.

Several rights organizations including the International Federation of Human Rights have called on the Bangladesh government to ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance without any delay. They have also asked prime minister Hasina to grant UN experts access to lead impartial investigations into cases of enforced disappearance.

“Furthermore the international community needs to pressurize the government to immediately stop this heinous crime and conduct thorough investigations into all cases and bring the perpetrators into justice,” the rights groups emphasized.