The death of former Egyptian president Mohammed Morsi following a court hearing on June 17 marks the end of a chapter in Egypt’s tumultuous history.

Mohammed Morsi became the first elected president of Egypt in June 2012 after a popular uprising which ended six decades of military rule in direct and indirect forms. However, within a year, popular protests erupted against his rule, leading to the military retaking power. The popular unrest against his rule was rooted in the widespread perception that the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), a group founded by Hasan al-Bana in the 1920s with the objective of creating an Islamic nation, had seized control over the state and was using its political power to convert Egypt into a country governed by strict Sharia laws. The secular opposition was mobilized when the new constitution was about to be finalized in June. The people were opposed to article 2 of the new proposed constitution which made Sharia a basic source of laws in the country. They also opposed article 4 which gave scholars from Al-Azhar university a consultative role in matters of the Sharia. The popular protests were fuelled by the disruption of some basic services.

Cairo’s Tahrir Square, the site of 2011-12 revolution which ousted Hosni Mubarak’s long-term dictatorship became, yet again, the epicenter of these protests. It was also alleged that Morsi placed persons from the MB in crucial state positions. He was accused of implementing the ideology of the MB through the new constitution.

The Morsi government tried to negotiate a deal with the opposition in June. Article 2 was justified as a long-term part of all the republican constitutions since the monarchy was overthrown in 1952. However, most of the opposition forces were not convinced.

The protests took an ironic turn when some of the participants gave the call for a military takeover. The defense minister in Morsi’s cabinet, major general Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, led a military coup and replaced him with an interim government in July 2013 and then by full-fledged military rule under his leadership in 2014. The brutal suppression of Morsi supporters in Cairo’s Rabaa al Adawiya in August was the beginning of massive state crackdown on the supporters of MB and other political opponents. Its activities were banned and most of its leadership was arrested. This has discouraged all kinds of political mobilizations since then and created an atmosphere which is worse than pre-2011 agitations.

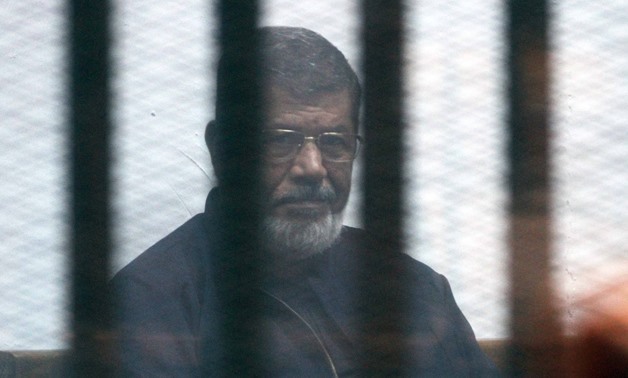

Morsi was charged with several crimes by the military rule, including espionage for Iran, Qatar and Hamas, insulting the judiciary and plotting terror attacks in Sinai. He was sentenced to death and for several jail terms. His death sentence however was later overturned. He had appealed against the rest of his sentence and was attending the hearing in one such case at the time of his death.

Morsi’s death raises several pertinent questions about the nature of current state of Egypt. Morsi was elected immediately after the massive popular protests which lasted for months. In the elections in May and June 2012, Morsi got just above 51% of votes. The total turnout was 51%. Within two years, in 2014, people turned to vote for a military general to power with more than 90% of votes. This time, the voter turnout was merely 46%. It is surprising to see that after a massive popular protest which ended the rule of a military dictator, half of the people did not feel motivated enough to go and exercise their choice of a ruler. The falling rate of popular participation in elections raises the question of legitimacy of the system, as well as a massive divide in the society. Both Morsi and el-Sisi have failed to acknowledge this divide.

Mohammed Morsi’s inability to manage the popular uprising within a year of his elections in a fairly credible election, a first for Egypt, originates from this failure. Since there are claims of him being the first democratically elected President of Egypt, it was his responsibility to acknowledge the divide and take proactive steps to bridge it.

Unlike their counterparts in Tunisia, where democracy survived the rule of a party with an almost similar ideology and almost similar divides, Morsi and his government did not end up choosing the path of moderation. They took their electoral victory as a popular endorsement of the agenda of the MB. They forgot that popular protests were not for an Islamic state in Egypt. Popular protests in 2011 were initiated by the working class and the youth. None of these sections were predominantly worried about the fate or status of religion in society and instead, raised numerous other issues, such as living conditions and political freedom. MB’s initial reluctance to join the protests was rooted in the realization that it could not endorse these concerns. Though several new political groups emerged in the course of the protests when the elections were finally held, MB won because of its organizational strength and not because it was the champion of the 2011 uprising. Instead of realizing this basic fact that Hosni Mubarak’s fall was a step towards creating a more progressive and forward-looking Egypt, Morsi and his government envisioned an Egypt which most of the demonstrators in Tahrir did not fight for. It is arguable that a lot of the protesters of Tahrir even felt betrayed when Morsi came to power. This may have contributed to the second round of protests in June 2013.

It is true that military’s intervention and ouster of Morsi was a bigger betrayal. El-Sisi’s regime has brutally suppressed all sections of the opposition. Workers cannot strike because it is a “public offense.” Most of the political formations which came into existence after 2011 have been banned, popular protests are illegal and so on. It is also a fact that the corruption of the Mubarak era has returned and the military’s control over most of the institutions is intact. El-Sisi, in order to please the religious constituency, has brought the same provisions in the new constitution for which Morsi was blamed. Sharia remains a guide for Egyptian law.

Meanwhile, Egyptian foreign policy is as pro-imperialist as ever. El-Sisi has stopped Gazans from accessing the Rafah border and supports Israeli bombings on Hamas. It wants to legitimize Israeli occupation of Palestine and is going to participate in the proposed Manama conference, a platform where Trump’s so-called “deal of the century” will be partially unfolded. Egypt is participating in the Yemeni war and playing a crucial role in the Libyan disaster. Thus, El-Sisi’s Egypt has emerged as a significant member of a pro-Israeli, anti-Iranian regional grouping led by the Saudis and directed by the US.

We will never know whether the Mohammed Morsi government would have created a different Egypt. The hope from the popular uprising was blurred by his actions. However, to be fair, he was denied the time he deserved. His almost one year in power, his quick ouster followed by six years of incarceration in the worst of the conditions, the deliberate negligence and the ruining of his health, leading to a sudden death in the courtroom – all this is a metaphor for democratic aspirations in the post-Mubarak Egypt. At least as of now, these aspirations are in a terminal condition as well.