Adelaide Gonçalves is a professor at the History Department of the Federal University of Ceará (UFC) and the driving force behind the Plebeu Gabinete de Leitura, a social library located at the headquarters of the Cearense Press Association (ACI), in the center of Fortaleza in Brazil. In this interview with Brasil de Fato, she discusses an important aspect of the library: the 201 editions of the Manifesto of the Communist Party in various languages, formats and editions. Among these are editions in comic book format, twine-bound and illustrated versions. She presents the Communist Manifesto as a iconic text of a political tradition.

Brasil de Fato: How did your collection of the Communist Manifesto begin?

Adelaide Gonçalves: The practice of collecting is a practice that may not be good. Sometimes, I think that collecting can be a sign of greed, individual accumulation, a treasure hunt of objects in many different places, which then are concentrated in the hands of a private individual. The practice that we have here in this social library, which for various reasons resembles collecting, comes from other interests.

In the case of the Communist Manifesto, we must highlight the fact that the very concept of the manifesto is of writing itself as a proclamation. A manifesto seeks to be an act, an inauguration of a tradition, a summons to those who feel identified, touched by that writing. A manifesto questions, summons, helps to tell the story in a concise way, in a succinct way and brings together topics, and is therefore, a kind of journey on a certain passage of history.

We have these two magnificent figures of the communist movement on a global scale, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. They were a duo who wrote magnificently and who dedicated themselves to thinking about the great issues of their time. The writing of the Communist Manifesto is about this uniqueness and it was groundbreaking.

The Communist Manifesto, which was made into a book, is an object made witness. Here, in this social library, we never stopped and said, “We are going to create a collection of the Communist Manifesto,” that is what is unique in the history of libraries. We began to walk in the old book stores, in the used bookstores, in the beautiful bookstores of Latin America and Europe and we encountered beautiful editions of the Manifesto, and we never could contain our excitement. Sometimes, there were very perfect instances – some editions were very expensive because the paper was of superior quality, or the cover was made from a more expensive fabric, and those days, we knew that lunch or dinner money would certainly be eaten into, but that edition went with us to the Plebeu Gabinete de Leitura in Fortaleza. I hadn’t prepared myself for this search, but they kept appearing in bookstores. It was as if one book called out to the other.

BdF: Could you talk about some of the editions in the collection of the Plebeu Gabinete de Leitura?

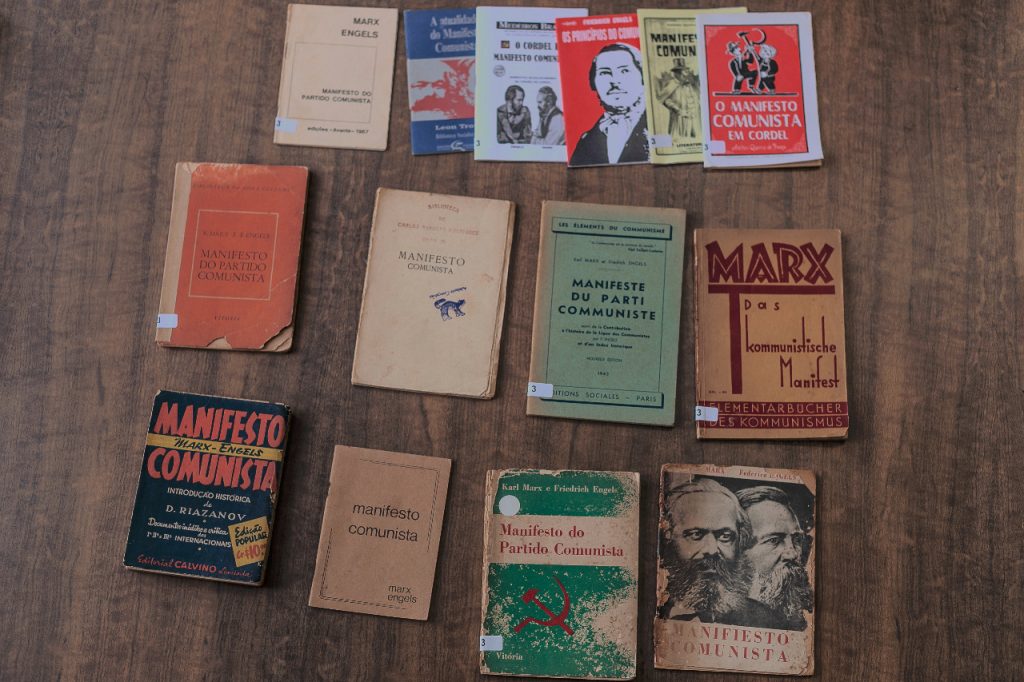

Adelaide: As of now, there are 201 editions, and I hope that those who are interested in this story and who have the same zeal that we are have, will give us more. Maybe next year, we will have 300 editions of the Communist Manifesto. I insist that the idea here is not the accumulation. The idea here is to demonstrate how a book has acquired layers of meaning over more than 150 years since its publication. There are editions that were produced, for example, in Portugal, under the heel of Salazar’s fascism; or in Spain, under the heel of Franco’s fascism; and in Chile, under Pinochet. And these editions do not have a publisher. I want to believe that they are clandestine editions that dared to defy the silence imposed by dictatorships and fascism, and were circulated clandestinely.

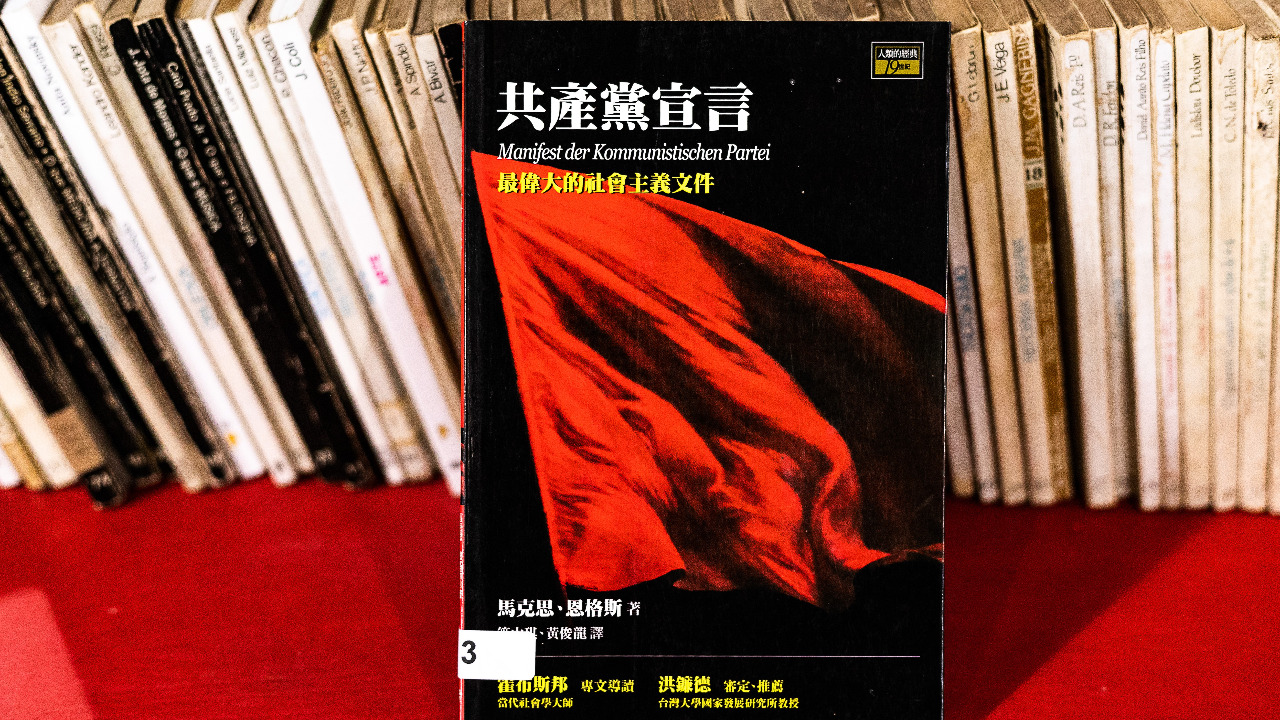

Other editions are brochures so modest in their printing that they indicate that the publishing groups did not have enough resources but were nonetheless seized with the urgency of spreading and reading the Communist Manifesto. And we also have some Manifestos in hardcover, on the best paper, with very beautiful covers.

We must also talk about this very vast and rich universe of editorial history that we have here: five comic book editions, giving us the opportunity to reach a new reader whose imagination demands illustrations. We have some editions with really beautiful prints. We are in the northeast of Brazil, and here, we have three very well cared-for editions of the Communist Manifesto in the cordel style (inexpensive printed booklets hung on strings in markets in the nonrtheast of Brazil), which opens up the possibility of reaching new readers.

BdF: In what languages do you have editions of the Communist Manifesto?

Adelaide: We have 58 editions from the Spanish-speaking world. We have editions from Barcelona that are in Catalan; we have editions from Bilbao that are in the Basque language. Then, there are editions from the Portuguese-speaking world. From Brazil alone, we have 57, from Portugal, 19. We have editions in English, French, German, Italian, Greek, Japanese, Mandarin, Esperanto, Hungarian, Arabic, Polish, Dutch, Danish, Russian and in many other languages.

BdF: What impact did the Communist Manifesto have on your life and education?

Adelaide: The quality of the writing in this small book impresses the reader. It is impressive how much can be said about these few pages. I read the Communist Manifesto – the first and a quick read – when I was a high school student. That little text was lent to me by a geography teacher who had a clear sympathy for communist ideals. Then, upon entering university, I read the Communist Manifesto twice. I had the good fortune to read it in a class on sociological theory, and also read it in militant circles. I no longer know how many times I have read that text myself. I also read it when we were going to publish an edition for militants.

Some sentences came out of the Manifesto and acquired a life of their own, gave titles to some books by historians, and some beautiful books of essays by great intellectuals. Certainly, a researcher such as myself will be able to attest that the words that emerged from the Communist Manifesto with great force are “Proletarians of all countries, unite!” This phrase has been printed in workers’ newspapers thousands of times.

BdF: Today, February 21st, a group of popular movements and organizations will carry out an activity called “Red Books Day” across the world, in which the Communist Manifesto will be read at various places. With regard to this action that celebrates reading and books, can you talk a bit about the role of books in the project of social transformation?

Adelaide: I was delighted when I heard about the Red Books Day. Reading the Communist Manifesto out aloud is a beautiful initiative. Here, in Plebeu, we are participating in this day of reading on February 21. I am inviting people to do an internationalist reading, in several languages.

I think that this year, the magnitude of our task is increasing. Since 2016, we have been facing a situation where thinking and books is under threat. We have had public statements from the Brazilian state about censorship; it is no longer veiled.

Last month, the minister of education said that in the future, the content of the books to be distributed to students in public schools will be changed. Recently, the fascist president [Jair Bolsonaro] complained about books that have too many words – a condemnation of books and a call for them to be taken out of circulation among citizens, especially the youth.

They know that books teach us to think; they lead us to question, and help us. An author knows that once the book is in the hands of the reader, it acquires a new author; then, there are thousands of authors.

For this reason too, we are happy about Red Books Day that honors our writers of all kinds, styles and latitudes. It is red because that was the color with which it was written. It is red because it has the life-giving blood of this writing that multiples, that prospers.

Original text by Monyse Ravena, Jornal Brasil de Fato Pernambuco