The 34-year-old case of the assassination of Sweden’s greatest political leader Olof Palme is coming to a close. In all the criminal intrigue and sleuth mythology that has shrouded the saga of Palme’s life and legacy, missing from the popular media coverage has been the vital internationalist, anti-imperialist project he led in Sweden, which was sabotaged that dark winter’s eve when he met his end.

The deceased Stig Engström, better known as the “Skandia Man”, has been named as the assassin. After an almost two-hour-long press conference by the prosecution investigation team, a sort of historical recap of chasing smoke, the Swedish people and the world are left with a hollow sense of justice. A vague offering of previously popularized means and motive of Engström: having been a part of a shooting club and “he ran in Palme-hostile circles.”

When the theories of motive began to stretch from the Apartheid South Africa intelligence agents to American CIA operations, those who know the important role Palme played in building an international solidarity network for our revolutionary organizations and national liberation movements did not think it fanciful to imagine that his murder was orchestrated by imperialist forces. Sweden had never had such a radical, socialist force as part of the international offensive against imperialism of that period.

In his early political life, Palme was pushed to the left when he was exposed to the different ways in which the established system deprived and dehumanized the majority. In his younger years, he deepened his socialist orientation of the world through the observations of the tax and labor systems in Sweden. While studying in the US in the 1950s he saw and was repulsed by the racist labor exploitation system and his travels in Asia revealed the many hardships of feudal and colonial societies. His familial relations to leaders the Communist Party in Britain, Rajani Palme Dutt and Clemens Palme Dutt, surely impacted his worldview; particularly since the mother of the pair, Anne Palme, was a young Swede married to an Indian surgeon at a time when multiracial couples were virtually unheard of.

From the late 1960s, Palme channeled his energies into building an international platform of fierce opposition to politics of domination, colonization, and exploitation. As a friend of the socialist projects in Cuba, Chile, Nicaragua and a firm supporter of the liberation fighters of Vietnam, Palestine, Western Sahara, Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Namibia, and South Africa, Palme was a remarkable leader in his ability to “straddle the worlds of activism and statecraft.”

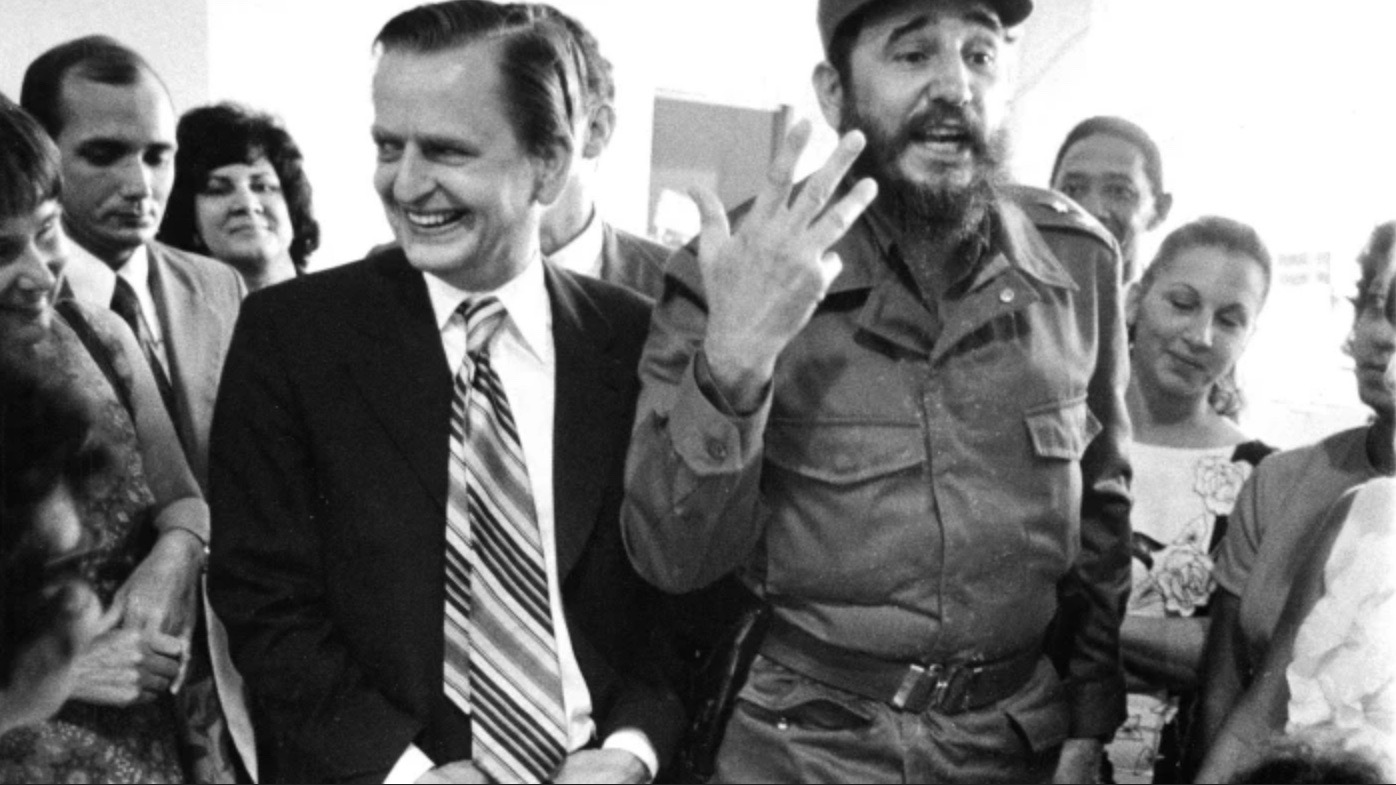

Whilst most European leaders bowed to imperialism and the US-led project of capitalist expansion, Olof Palme drew inspiration from relations with Fidel Castro in Cuba and built relations with leaders and movements in the anti-colonial front during the late 1960s; developing strong ties with the likes of South African leader Oliver Tambo and Yasser Arafat of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

In his earlier days working as a leader in government, he deftly wrangled political space to host the first International War Crimes Tribunal in Stockholm. Organized by British socialist Bertrand Russell and with the participation of key public voices, such as Jean-Paul Sartre, the symbolic tribunal put the United States on trial for its crimes in Vietnam and found it guilty. Though no punitive measures could be taken, this was an inimitable moment in the struggle to win over the court of public opinion and correctly characterize the United States as an imperialist and destructive power.

During his time as Prime Minister, Sweden contributed significant social, political, and material resources and support to the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movements. Through Palme’s leadership, Sweden was the first to enforce economic sanctions against Apartheid South Africa. Speaking to the “Swedish People’s Parliament against Apartheid” on 21 February 1986 , just seven days before his assassination, Palme unequivocally condemned the Apartheid government for their empty proclamations to reform the racist, capitalist state. Vitally, he was firm in understanding that international solidarity was a strategic necessity in the struggle for liberation:

“A system like apartheid cannot be reformed but must be abolished… We are all implicated….If the rest of the world decides, if people all over the world decide that apartheid is to be abolished, the system will disappear…From those who regard people’s longing for liberty as a potential cause of global contest between different superpowers, there is resistance. And all this, in my opinion, is another example of madness, because the apartheid system is also a classical example of a threat to peace which people must jointly abolish.”

For the Swedish people – though still existing in small pockets – the then growing internationalist politics of radical, participatory agency by an engaged citizenry seems to have died with Palme. Regarding the political climate in which Sweden’s Covid-19 response unfolded, Adele Lebano described how the Swedish citizenry seems to be locked in a stupor produced by the relative welfare protection and material comforts, and the political structures largely serving to “encourage citizens to suspend their capacity to choose.” The individualism and consumerism, xenophobia, rising popularity of anti-immigrant and right-wing populism, the sheepish acceptance of the sine qua non of global capitalist exploitation, are all embedded in contemporary Sweden. A far cry from the politics of their impassioned leader who famously declared, “There exists no ‘they and we’ only ‘us’. Solidarity is and has been indivisible.”

For Palme, the process of creating democracy was built by the people and liberation would never come in a world of class division: “Democracy…should be a road leading to the liberation of the people. We do not wish to have a future where the rich, with the aid of force and oppression, shall guard their privileges. We want a world of equality in which people can live.”

Those who want a resolve to the mystery of his murder and honor his memory, can do so in reviving his radical political legacy.