“Slavery 400 years ago, slavery today. It’s the same but with a new name.” – Ruchell Cinqué Magee

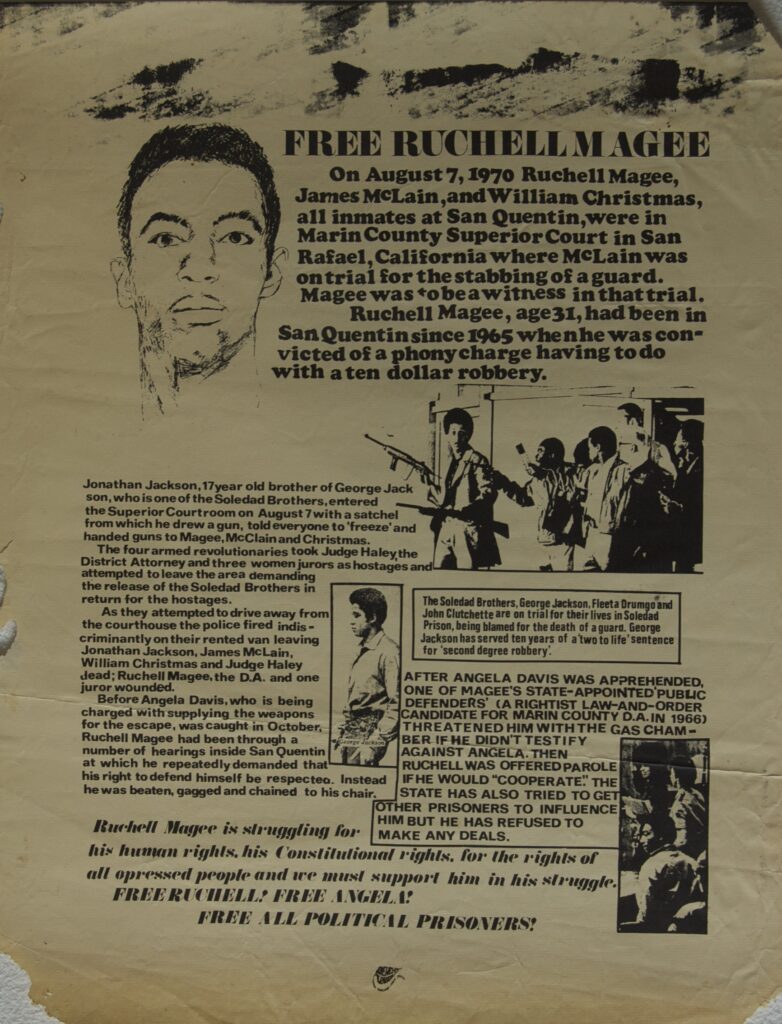

Ruchell “Cinqué” Magee is the longest held political prisoner in the United States. At 83 years old, he has lived only 16 years and six months outside of prison. The rest of his 67 years have been behind bars. What crime could possibly warrant this level of punishment?

For Ruchell, the length of his sentence is directly tied to his political activity as a prisoner. Although the United States government speaks at length about the political prisoners of other countries, often as a way to justify policies of regime change or coercive measures, the US keeps quiet about its own political prisoners. These prisoners extend beyond the infamous Guantanamo Bay. Many go back as far as the era of radicalism and uprising of the 1960s and 70s, and many, like Ruchell, have ties to the Black liberation movement.

Why has the United States kept these primarily peaceful and elderly prisoners behind bars for so long? What threat do they pose to the powerful US government? For answers, Peoples Dispatch interviewed Kameron Hurt, organizer with the Party for Socialism and Liberation and the Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee.

A legal lynching

The story of Ruchell Magee, like the story of so many Black prisoners, is a story of the legacy of slavery in the United States. Ruchell was born in 1939 in Louisiana, in a time when the Southern region of the United States was mired in “Jim Crow” laws and racist terrorism, in which both the state and white vigilantes enforced strict racial segregation.

At age 16, Ruchell was sentenced to prison for 8 years for “aggravated attempted rape” for his relationship with a 23-year-old, married white woman. False charges of rape by Black men against white women were not uncommon in the Jim Crow era, often with devastating consequences. In 1955, the same year Ruchell was accused of rape, Emmett Till was brutally lynched for allegedly whistling at a white woman. As discovered by journalist Ida B. Wells many years prior to Ruchell’s birth, rape was the most common accusation against lynching victims. Lynching was an infamous terror tactic used by white vigilantes against Black people in the Jim Crow South, many times upheld and sanctioned by the courts. And in the context of US prisons, many prison activists refer to unfair trials of Black people as “legal lynchings”.

Ruchell spent eight years in the Angola prison in Louisiana as a result of this accusation. Angola itself was a former plantation, named after the part of Africa where its slaves originated.

As Hurt described, Angola “is called a former plantation but we know that with the way that the mass incarceration system is set up, it doesn’t have to change a lot to go from a plantation to a prison.” Currently, the 75% Black prisoners in Angola are forced to pick cotton in the same fields that slaves used to work on, paid only a few cents per hour. And especially at the time Ruchell was incarcerated, Angola had a fearsome reputation for brutality and squalid conditions. Only three years before Ruchell was accused, 31 prisoners cut their Achilles tendons in protest of prison conditions.

A victim of incarceration turned people’s lawyer

Ruchell was paroled in 1962 at age 23, disinherited from his property, and forced to move out of Louisiana. He relocated to Los Angeles, where he would enjoy a mere six months of freedom. Ruchell was once again arrested in 1963 in a dispute over $10 worth of marijuana. Ruchell’s arresting officers beat him so badly that he was hospitalized for five days.

Ruchell steadfastly denied these accusations, but Ruchell’s court-appointed attorney was not on his side, refusing to use the hospitalization records in his defense. Ruchell himself brought up the records in his closing arguments. The jury found Ruchell guilty on all charges. Being a prior felon based on his “aggravated attempted rape” conviction, he was sentenced to life in prison under California’s indeterminate sentencing law.

Ruchell, a tireless fighter, requested the court transcript records after his first trial. He believed that the portions in which he referenced his hospitalization would prove his theory that the police framed him to protect themselves from the consequences of their brutality. However, once he received that transcript, the state had wiped it clean of his mention of hospitalization.

Ruchell, now in his second trial for the same crime, now found himself in a struggle against not only the judge (the same one from his first trial), but also his fourth court-appointed attorney who, against Ruchell’s will, plead him guilty by reason of insanity. His attorney called no witnesses and subpoenaed no evidence in Ruchell’s defense. When Ruchell objected, he was gagged and beaten. He did not win this second trial.

The similarities to the era of slavery abound, in which, by law, Black people “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect”. Even today, millions of Black people in the US continue to be caught up in the system for similar reasons as Ruchell. According to the ACLU, Black people are four times as likely as whites to be arrested for marijuana possession. Many working class people across the US languish in prison for petty crimes or crimes of poverty, due to harsh sentencing laws such as indeterminate sentencing or mandatory minimums, driving the US prison population to the largest per capita in the world, by far.

But Ruchell refused to be but a victim of the incarceration system. He fought back every step of the way against the system that seemed determined to keep him in a form of legal slavery, not only for himself, but for others. “Ruchell definitely kept up his work and did a lot of amazing, what’s often called ‘jailhouse lawyer’ work. He was a people’s lawyer,” Hurt told Peoples Dispatch.

“He was basically self-trained and he supported a lot of people in their release, because he witnessed what the corruption of the system could do. He felt as though his own trial was fraudulent. So he has continually spoken out about that, and even the wrongful death of prisoner, Fred Billingsley, who was beaten and tear gassed to death in his cell in San Quentin prison in February 1970. Ruchell did a lot of work to help achieve a settlement for the Billingsley family after that terrible incident.”

A slave rebellion

In fact, it was Ruchell’s fight for justice for Billingsley which led to his involvement in the infamous Marin County Courthouse Rebellion. This hours-long uprising in 1970 is the crux of the reason that Ruchell is imprisoned to this day.

On the day of the Rebellion, Ruchell was testifying on behalf of fellow prisoner James McClain charged with assaulting a prison guard in retaliation for Billingley’s murder. Ruchell, and another prisoner, William Christmas, were in court to argue McClain’s innocence, arguing that the accusation stemmed from the state’s effort to crush resistance following Billingsley’s death.

It was in this courtroom that 17-year-old Jonathan Jackson, brother to George Jackson, rose from the audience of the courtroom and pulled out several guns. Jackson announced a takeover of the courtroom, intending to win the freedom of his brother and two other prisoners who had been falsely accused of killing a prison guard. After passing guns to McClainn and Christmas, who invited Ruchell to join them, Jackson took Judge Harold Haley, District Attorney Gary Thomas, and a few jurors as hostage.

This incident, which fellow Black prisoner Larry West described as a “slave rebellion”, sounds like something out of work of fiction to those familiar with the unyielding reputation of the US incarceration system. But the uprising was short lived, and this great transgression on the reputation of the state was punished severely. As Jackson drove away from the courthouse with hostages in tow, Marin County police and San Quentin guards opened fire, murdering Jackson, Christmas, McClain, and even Judge Haley. As Ruchell described, “I saw old man Haley cut down by the pigs, while waving his hands and hollering to the pigs … ‘don’t shoot, don’t shoot …’” The state, in its indiscriminate violence, was willing to cut down its own judge. Authorities then pinned this crime on Ruchell, the sole survivor of the massacre.

“My fight is to expose the entire system”

“You have to deal on your own tactics. You have a right to take up arms to oppose any usurped government, particularly the type of corruption that we have today.” — Ruchell “Cinqué” Magee

Participating in such a historic rebellion led Ruchell to identify deeply with Joseph Cinqué, who led a slave revolt on the ship La Amistad, and who successfully defended himself in the US Supreme Court on the grounds that he was being enslaved through the then illegal African slave trade. Ruchell takes on the name “Cinqué” as his own. As Hurt wrote for Liberation News, “Magee has continuously drawn parallels between Cinqué’s just struggle against slave traders in 1839 and his attempt to break his unjust, racist confinement as a prison slave in 1970.”

As Hurt described to Peoples Dispatch, “Ruchell is the only survivor out of those who participated in the act of liberation. Therefore, he’s seen as the person who needs to be made into an example.” Magee was indicted for the rebellion, but from the beginning he applied the same principles of fighting for the freedom of prisoners, who he viewed as enslaved, which brought him to Judge Haley’s courtroom in the first place. Ruchell did not leave his defense to educated, upper-class lawyers, as was and still is the norm. Ruchell largely served as his own defense, setting out not only to exonerate himself from murder but also to prove the corruption of the entire California court system.

“I am going to show you and prove to you that the entire state of California judicial system…don’t care nothing about the little man’s rights,” Magee spoke up in court. “It’s not just Magee but any black man that they feel they can get away with, sneak and hide and convict him through fraud and thereafter place fraud records upon him. Then, when he attempts to overcome this, he is overpowered with all types of racist restraints, falsely accused…you will find you have hundreds of thousands of people illegally held in slavery…”

The California courts were so threatened by Ruchell’s language that they chained him, gagged him, and even had his own attorney threaten him with the gas chamber if he didn’t incriminate his co-defendant, Angela Davis. And to this very day, Ruchell languishes in prison as the longest serving political prisoner in the United States.

“There’s a certain prestige that the court system, the prison system has or likes to think it has, that it allows no escapes, allows no breakout attempts,” Hurt articulated. “It’s almost like heresy. It’s an unheard of thing that someone walks into a courtroom, breaks out people who are on the stand and then actually is able to make it out of the court…We believe that in California, there’s this deep, long memory, especially within those sorts of repressive apparatuses that leads them to believe that if they were to let this person out, this would be a symbol of a weakness of the state.”

As Ruchell himself said, “My fight is to expose the entire system, judicial and prison system, a system of slavery. This will cause benefit not just to myself but to all those who at this time are being criminally oppressed or enslaved by this system.” What Ruchell symbolizes, to those incarcerated outside and inside, is a person willing to rebel against a system perhaps even more powerful than slavery in its sheer size and influence: the US prison system. As Hurt described, Ruchell’s crime is heresy in his unmasking of the system.

—

Hurt and the Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee demand California Governor Gavin Newsom to immediately commute Ruchell’s sentence so that he can be released. He is now 83 years old, and although he is due for parole in 2024, any year can be his last.

“Not all political prisoners are arrested because of their political activity, but some are politicized while in prison,” Hurt said. “And then when they come out, they’re able to spread what they have learned, how they’ve grown with the world. And we believe Ruchell has a lot to teach the community and talk to people about. So we hope that we’ll have a day where Ruchell is able to talk to young prisoners or young people who are at risk in the community, to help share insights and build a new world.”