In July and August of 2022, monkeypox received a lot of attention globally, with daily articles recounting the total number of cases. However, in recent months, the illness seems to have disappeared from the news.

Cases have been declining in the United States and Europe since mid-August, and epidemiological models have suggested that monkeypox will not become pandemic in these high-income countries. However, there is a significant disparity in who is acquiring the virus—both within and between countries.

For example, reports in the US indicate that Black men, and men who have sex with men are more likely to acquire monkeypox. These same populations are the least likely to access the vaccine.

It is worth bearing in mind that, while the US has reported an estimated 35% of global cases, it has procured 80% of the available global monkeypox vaccine supply. Meanwhile, Brazil, the country with the second highest number of reported cases, has yet to receive any vaccines. It is estimated that all of Latin America will only receive 100,000 doses this year.

Monkeypox has been endemic in a handful of Central and West African countries for decades. Episodes caused by the virus occurred regularly before the global outbreak. The continent has yet to receive even one vaccine dose. On the other hand, in 102 out of the 109 countries which reported cases during the current outbreak, monkeypox had not historically been present—yet countries with more money managed to secure most of the vaccine stockpile.

Response dictated by the Global North

The Wellcome Trust has called monkeypox “a stark reminder of the weaknesses of the world’s ability to prepare and respond to pandemics.” However, the world does not sit on an equal playing field. It is clear that the “global” monkeypox response has been dictated by the actions and priorities of a handful of high-income countries in the Global North.

Monkeypox had not been prioritized as a potential pandemic disease before the current outbreak. At present, there are no specific treatments or vaccines for monkeypox, with the entire world relying on the efficacy of the smallpox vaccine.

While there are potential treatments in the works, such as Tecovirimat, this research has lacked urgency, funding and prioritization. Dr Piero Olliaro, an academic conducting research with Oxford University, said, “Despite being endemic to parts of Africa for decades, attention is only paid when the disease hits high-income countries.”

Prioritization has also been a significant issue in the production and supply of smallpox vaccines for monkeypox. This indicates yet another way in which high-income countries have monopolized power through the hoarding of, and subsequent inequitable access to, smallpox vaccine supplies.

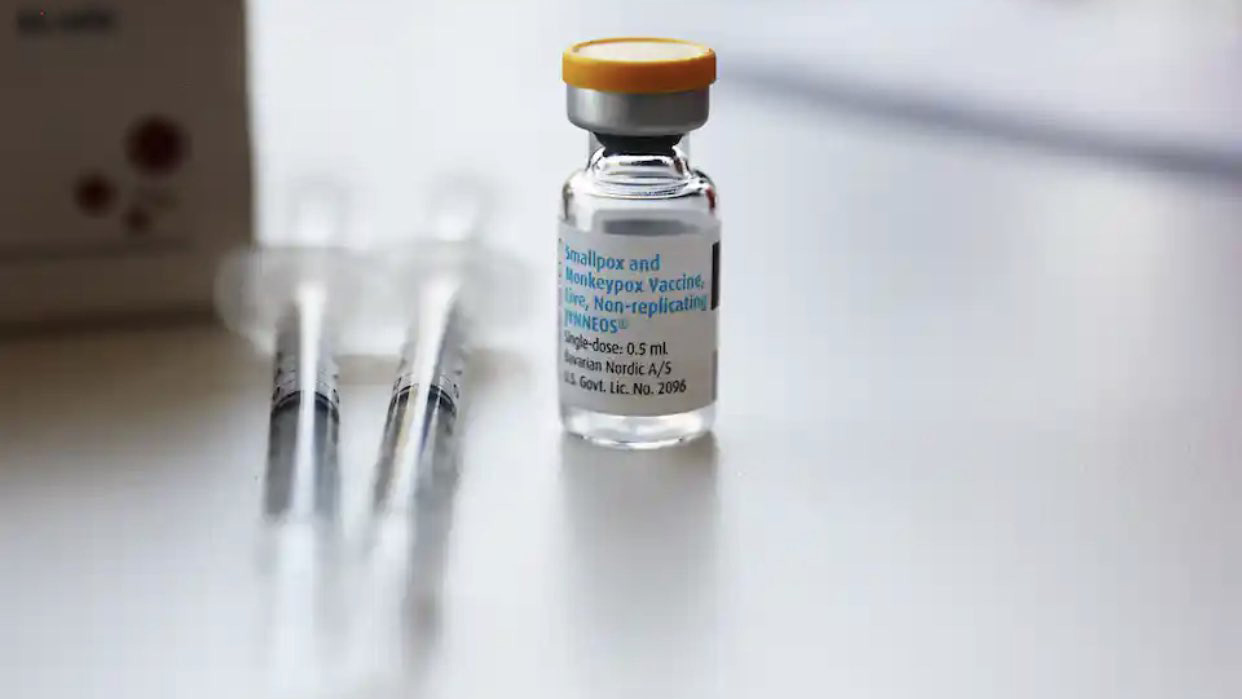

Responding to monkeypox, as we saw during the HIV and COVID-19 pandemics, pharmaceutical companies and high-income countries are putting profit ahead of people’s health and lives. There is only one company, the Denmark-based Bavarian Nordic, who controls the production, supply and use of the smallpox vaccine, Jynneos, that is being used for monkeypox.

Bavarian Nordic holds the patent for Jynneos. They have the ability to dictate who can make or buy the vaccine, when, and at what price. This is despite the fact that an estimated USD $2 billion of US public funding has been invested into the research and development of the vaccine.

Bavarian Nordic had not prioritized the smallpox vaccine. In fact, the company ended their manufacturing of the vaccine in spring of 2022. This left just 16 million doses of Jynneos available worldwide during the current monkeypox outbreak. Most of these doses have been bought by the UK, US and EU. However, the UK has already nearly run out of supply and is rationing doses.

Despite offers from South African manufacturer Aspen, Bavarian Nordic has continued to concentrate production of the vaccine in the Global North. The company has reportedly priced the vaccine for all buyers at over $100 per dose, making it not only inaccessible but also unaffordable for many countries. Meanwhile, shareholders of Bavarian Nordic have already seen its stock price triple.

In a recent report, Public Citizen, a US-based not-for-profit, found that at least nine global vaccine manufacturers have experience in making vaccines similar to the monkeypox vaccine. “Chick embryo fibroblast” cells are central to Jynneos production. The nine identified manufacturers already use this technology to make vaccines for diseases such as measles, mumps, and rabies. Six of these manufacturers are based in low and middle income countries: Brazil, India, Indonesia and South Africa. They sell vaccines similar to Jynneos for $4 or less per dose—nearly 30 times less than the estimated $110 price of the monkeypox vaccine. A simple act of breaking the monopoly of Bavarian Nordic can be a huge leap forward in prioritizing lives over profit.

The African continent has not received a single dose of the vaccine. Ahmad Ogwell, head of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, has warned that this bears the hallmark of the inequality experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. This inequity is made only more stark by the fact that clinical trials for monkeypox vaccines have been conducted in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where monkeypox is endemic, but where no doses are available.

Alongside the hoarding and monopolization of vaccine supply, the availability of tests and treatments for monkeypox is also an issue. Tecovirimat, the treatment currently undergoing clinical trial stage, is part of an “extended access use program” which provides early access to a medicine which has not yet received approval. However, Tecovirimat is not registered for use in Central Africa so the expanded access program does not apply, meaning the drug cannot be tested in countries where monkeypox is actually endemic.

Similarly, while testing and surveillance are critical elements in disease response, many have lacked access to monkeypox tests. In the US, a scientist working at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention could not access a test when he suspected he may have had the virus. In Brazil, where one in twelve monkeypox cases have been reported, there are only four testing centers for the entire nation. In addition, researchers have warned that testing “is a huge problem” across the African continent, with difficulties accessing tests and severe delays.

What’s next for monkeypox?

The current global outbreak of monkeypox clearly demonstrates the consequences of power in global health. Priorities of high-income countries have prevailed, with unequal distributions of cases, disparities in access to vaccines, and a lack of available tests and treatments. Zain Rizvi, Research Director at Public Citizen, wrote, “A better approach could have recognized the centrality of public power to public health.”

While monkeypox might have fallen off the agenda in high-income countries, civil society groups are steadfast in pushing for attention to and action regarding the inequalities in the global response.

As Ogwell said, “The solutions need to be global in nature.”

“If we’re not safe, the rest of the world is not safe.”

Molly Pugh-Jones is a health justice advocate working as Advocacy Officer for UK-based organization STOPAIDS, where she focuses on access to medicines.

People’s Health Dispatch is a fortnightly bulletin published by the People’s Health Movement and Peoples Dispatch. For more articles and to subscribe to People’s Health Dispatch, click here.