The government of Workers’ Party president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, which was sworn in 5 days ago, has considerable challenges ahead of it to tackle the social, economic, political, and public health crisis which faces Brazil. During the four years of far-right rule under Jair Bolsonaro, the health sector was one of the hardest hit by budget cuts, a move which exacerbated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The budget proposal for Brazil’s health sector for 2023, left by the government of Jair Bolsonaro, proposed a reduction of investment in the sector by R$ 22.7 billion reais (USD $4.2 billion). While Lula’s new health ministry is working on reformulating the budget, Bolsonaro’s parting gift mirrors the overall management of the sector by the right-wing government, especially with regards to the Unified Health System (SUS).

Even before he was elected, Bolsonaro advocated for a private sector driven vision of the SUS in his government program. The document did not contain a proposal to guarantee more funding for healthcare.

In 2019, when the extreme right-wing administration began, the sector’s budget was already compromised because of the spending cap. The spending cap was passed as a Constitutional Amendment when Michel Temer occupied the Planalto Palace, following the coup against former president Dilma Rousseff.

With the Constitutional Amendment, the investment in the SUS, which was 15.77% of net current revenue in 2017, fell to 13.54% in 2019. The text provides that the amount will remain the same, without any kind of adjustment above inflation for the following twenty years.

Getúlio Vargas de Moura Júnior, deputy coordinator of the Budget and Financing Commission of the National Health Council (Cofin/CNS) recalls that the underfunding of the SUS is a historical problem.

“In the 1988 Constitution and in the SUS law in 1990, we were already debating health financing. It never had the necessary resources to meet all the challenges that are posed. So, we need to understand that from 1990 to 2016, the resources were always less than the needs. With the spending cap, starting in 2016, this gets worse. An area that, historically, has not had the necessary resources, then underwent a process of hollowing out, of dismantling, which makes it even more fragile.”

The president of the Brazilian Association of Health Economics, Franciso Funcia, professor at the Municipal University of São Caetano, says that the losses resulting from the spending cap and the Bolsonaro administration’s cuts may reach R$ 60 billion (USD $11.1 billion). Over the two decades expected with the spending cap in place, Brazil would lose 30% of investment in health.

“For those who like fiction movies, if we lived in the reality of a fiction movie, you would also freeze people’s lives. You would freeze society and, 20 years later, everyone would be back where they were. But life goes on, doesn’t it? The health needs of the population, the education needs continue. The population grows at a rate of 0.8% per year, the growth rate of the elderly population is 3.8% per year. Unfortunately, it’s a horror story.”

The only move by Jair Bolsonaro’s government to expand the area’s budget occurred in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. In March of that year, a state of public calamity was declared, which opened the possibility of breaching the spending cap. Even so, the application of resources was slow. By the first week of June 2020 most of the funds had not even been used.

At the time, Brazil already presented very high levels of infection and deaths. For four months it remained at a plateau of more than six thousand deaths per week due to the coronavirus.

Months later, the COVID’s Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI) would reveal a report from the Public Ministry of Accounts that showed how SUS funds were redirected to finance military expenses.

For 2021, with the planet still facing COVID-19, the government presented to the Congress a health budget with similar numbers to those before the global emergency. Between February and August the spread of infections escalated. Brazil registered more than 20,000 fatal cases every seven days. The system collapsed, and there was a lack of medicine, respirators, oxygen, and protective equipment for the teams.

The budget for 2022 saw a 20% reduction from the previous year. Family and community physician Aristóteles Cardona, from the National Network of People’s Doctors, says that the budget squeeze was noticeable in several daily aspects. As the SUS waiting list multiplied due to the pandemic, the situation worsened.

“We began to experience an increase in the pent-up demand for care for chronic conditions and other problems that were not being prioritized during the most critical moment of the pandemic. Some with complications and a greater cost, financially, emotionally. We are in situation where we are back to having very heavy burdens. There are municipalities in which we have not yet fully returned to the level we had before the pandemic of elective surgeries, of outpatient consultations with specialists. It simply hasn’t come back. It’s a problem on the back of primary care,” he alerts.

Bolsonaro’s administration ended with Brazil on the list of countries that had the most cases and deaths due to COVID-19, a decrease in health investment, and insufficient data to understand the size of the problem.

In four years, the area had four ministers: Luiz Henrique Mandetta (União Brasil), Nelson Teich, Eduardo Pazuello (Liberal Party) and Marcelo Queiroga. The comings and goings amidst the greatest health crisis of the century exposed the inefficiency in dealing with public health.

“To see the dismantling, we just have to look at the fact that there was this need for immediate, urgent budget recomposition for 2023. The motto of Juscelino Kubitschek and his growth plan, when he was president of Brazil in the 50’s was to grow 50 years in five. [The government of Jair Bolsonaro] implemented a motto that was set back 40 years in four. That is what happened. In many areas, we went back to the 1980s,” Francisco Funcia points out.

SUS primary care in danger

In 2020, the Ministry of Economy, headed by Paulo Guedes, included SUS primary care in the Bolsonaro government’s privatization program. After heavy criticism and pressure from civil society and opposition members of Congress, the measure was abandoned.

However, the attacks against SUS primary care was not new and did not stop there. In the previous year, the government had already deactivated the Mais Médicos program, which hired professionals to work in places that lacked care.

Traditional communities, towns in the countryside, municipalities with difficult access and suburbs were the most benefited by the project, implemented during Dilma Rousseff’s government. The president’s measure was symbolic for the extreme right-wing project that Bolsonaro represents. At the end of the program, he instigated a diplomatic crisis which resulted in the departure of Cuban doctors from Brazil that were part of the program.

What followed was a series of measures to negatively impact the performance of the internationally praised SUS. In 2020, the government changed the method of financing primary care which decreased funds for the system in the largest cities in the country. This harmed the majority of the Brazilian population that lives in the cities and directly affected those living in the the poor neighborhoods across the country.

Physician Aristóteles Cardona explains the damage caused by the system being managed with a liberal and pro-privatization understanding of primary care.

“What was predominant in this whole process is that, essentially, all the directives we had in the Ministry of Health were from people who didn’t have the slightest knowledge about primary care, about its importance. Not to mention the lack of commitment from a good part of them. Even today, there are studies saying that primary care – with all its capillarity, with all its structure in the country – was very poorly used. We could have had another scenario. It is the combination of incompetence, lack of knowledge, and lack of commitment to the health of the Brazilian population, which led to this.”

Pandemic

A fully functional regionalized care network focused on prevention was severely lacking in the pandemic. With SUS primary care operating at full capacity, Brazil could have tested more, vaccinated faster, and reinforced educational campaigns about the health emergency.

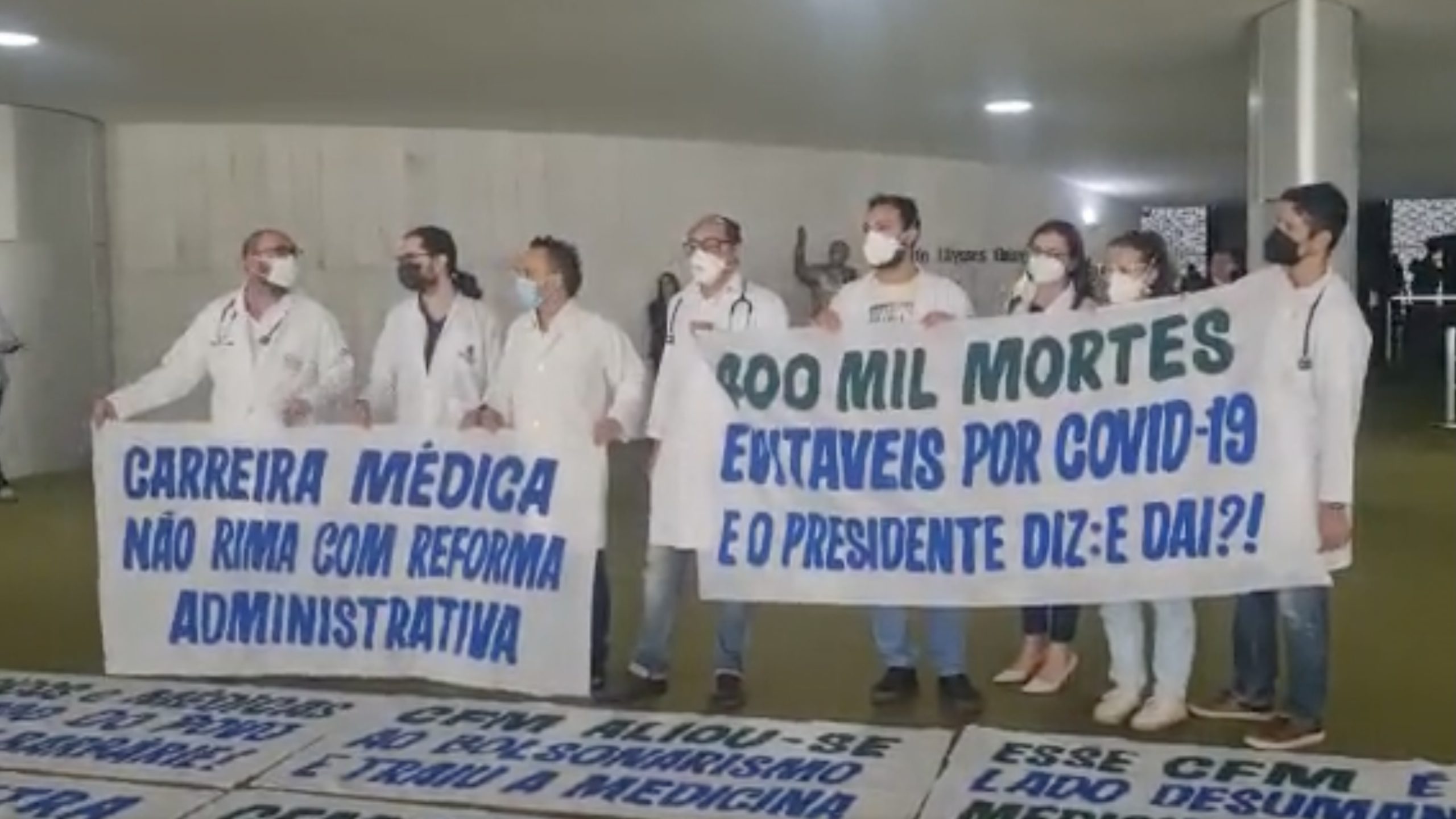

But the reality was far from this. Jair Bolsonaro’s management during the global emergency earned him an indictment for genocide at the Hague Tribunal.

Getúlio Vargas Moura Júnior calls this a tragedy and says that lack of funding was at the center of the problem. The lack of priority, planning, and denialism at the upper echelons of the government cost lives that could have been spared.

“What further deepened the health tragedy in this last period was trying to combat the pandemic with an unstructured and uncoordinated health system and a weakened SUS. The resources that were delivered…through pressure from society, were resources invested drop by drop. In such a way that the federal government of Bolsonaro exempted itself from confronting the pandemic. It was slow in developing and acquiring vaccines, creating a perfect storm. So, for us, the funding is linked to a policy of death, a policy of delay that has run the country in this last period.”

In January 2021, an evaluation of the government-determined jurisdiction on COVID-19 indicated that there was purposeful action to prevent the fight against the coronavirus. According to the document, the more than 3,000 laws, provisional measures, decrees, and other mechanisms did not meet the needs created by the crisis and acted against controlling the spread.

Authored by the Center for Research and Studies in Health Law (Cepedisa) of the Faculty of Public Health (FSP) of the University of São Paulo (USP), in partnership with the NGO Conectas Human Rights, the survey was the basis for a criminal complaint to the Attorney General’s Office signed by a group of jurists.

The group pointed out that the government seems to believe that the spread of the virus is a strategy to confront the pandemic. Bolsonaro was also accused of “infraction of preventive health measures, irregular use of public funds or income, prevarication, and danger to the life or health of others.”

Denialism, dismantling, and lack of investment permeated the government response. With the arrival of the vaccine, new accusations emerged. The CPI on COVID denounced that the Ministry of Health and the Planalto Palace ignored emails from laboratories interested in selling the vaccine for months. There were also identified attempts to charge bribes in transactions with representatives of the products.

The challenge of the new government

Already in the election campaign, last September, Bolsonaro determined a series of cuts in essential health projects for next year’s budget. He cut 45% of the amount destined to cancer treatment in the country. The amount was allocated to the secret budget for parliamentarians.

Another 12 programs of the Ministry of Health were affected in the forecasts for 2023. The distribution of drugs for the treatment of AIDS, sexually transmitted infections and viral hepatitis, for example, lost R$ 407 million (USD $76 million). The Popular Pharmacy lost 60% of its resources. Responsible for the free supply of high-cost drugs, the action will have R$ 1.2 billion (USD $223 million) less to operate in 2023.

In addition to signaling that it will recompose programs depleted by Bolsonaro, the Lula government seeks ways to bring back the investments in health with the Transition Proposal of Constitutional Amendment. Franciso Funcia points out that it is necessary to act urgently to change the fiscal rule which dictates the spending cap and the minimum budget for healthcare. He also cites the need to increase public investments in the sector, especially by the Union, and the importance of health policies being present in the definition of economic policies.

“The health care minimum budget cannot be linked to revenue, because revenue varies according to, let’s say, the rhythm of economic activity. When the economy is growing, when the economy is doing well, the revenue grows. But when there is an economic crisis, revenue falls. It is precisely during the crisis that you need to have more spending on health. It is illogical to have less resources for health when revenue falls, because exactly because of the crisis, you have more demand.”

The size of the obstacle is considerable, since the dismantling occurred not only by direct decisions, in health, but also with the deterioration of other areas of life. From culture to the environment, passing through education, everything influences the health of the population. Social conditions, violence, unemployment, famine and hunger have a direct impact. The negative impact of the Jair Bolsonaro government in all of these areas has contributed to further depleting the national network of care.

“If we consider that health is transversal, we see that in sanitation, in the surveillance issue, in the fight against hunger and poverty, all these other areas, much more money was taken from health. Because not implementing these public policies ends up overloading [health] as well. We see health as a construction, a right, a social construction. We noticed that, especially in this last period, before the pandemic, healthcare was seen as a commodity. However, the only health plan that seven of every ten Brazilians has is the SUS. [Privatization] was never a solution that would contemplate most of the population,” Getúlio Vargas de Moura Júnior points out.

Even in the face of dismantling and collapse, by the end of the government of Bolsonaro, the Unified Health System is even more valued by the population. In Aristóteles Cardona’s opinion, this is key to keep in mind, but the path to recover Brazilian public health will be long.

“It is important to emphasize the perception of how much SUS has been more valued by the population. We notice this in our daily lives and there are surveys that show this. I think that, like many areas in our country, we will need to go through a rebuilding process. Rebuilding is always more difficult. Destroying is easy. We are going to need a huge effort and we are going to have to be patient. There is a lot of data that we don’t even know. It’s a scorched earth.”

This article was first published in Portuguese at Brasil de Fato.