Lee en español aquí

“We are a generation totally interested in taking power,” says Bárbara Navarrete, the new secretary-general of the Communist Youth of Chile. This generation came of age with examples such as Gabriel Boric, Chile’s president, who is only 37 years old, and Camila Vallejo, the president’s chief of staff, who is only 35. By constantly engaging in the political arena and reaching the highest levels of the government, people like Boric and Camila—as they are known—“push us to get involved, to take sides,” Navarrete says. Fifty years after the coup that devastated Chile, people like Navarrete oscillate between hope in a government led by former student leaders (such as Boric and Camila) and devastation at the defeat of a new constitution in 2022. They also have to contend with the rise of the right wing, which now holds offices in the legislature, including the presidency of the Senate.

Navarrete’s own story is an example of, in her words, “the crossroads of experiences that affect this new generation in their way of doing politics.” Her family directly experienced the consequences of the dictatorship in a peripheral part of Santiago. Born a few years after the end of the dictatorship, Navarrete learned about politics in the student mobilizations of 2011, while she studied at an important women’s school in the city. For nine months, the students took over the school in protest against Chile’s private education model. Two political tendencies dominated the school—anarchism and communism; Navarrete opted for the latter.

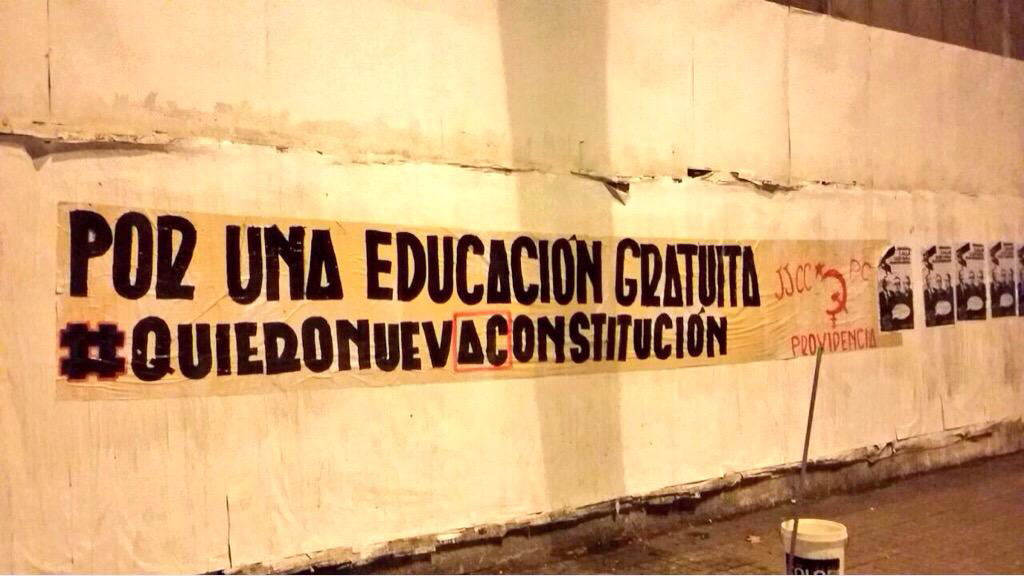

During her time in the student protests, Navarrete says she saw “clearly the institutional alienation” of her generation. They may have grown up after the dictatorship, but they were surrounded by its institutions (including the coup constitution of 1980). “We felt,” she says, “a detachment from laws and institutional culture,” and they were left with a feeling of “incomprehension” toward the institutions’ legitimacy. This resulted, she says, in “an overwhelming need to change everything, including the constitution.”

The results are not random

Enshrining a new constitution for Chile before the 50th anniversary of the 1973 coup would have been a major achievement. But the draft constitution—produced with immense democratic input—was defeated in the elections on September 4, 2022. In the aftermath of that election, the government set up a committee of experts to produce a new draft that would be approved by 51 members of a constitutional council (elected by direct vote on May 7, 2023). The right-wing Republican Party won 35.4% of the vote, which gave it 23 constitutional council members. The Communist Party of Chile headed a coalition that won the second-most votes, with 28.6%.

For Navarrete, the victory of the Republican Party “is neither a surprise nor an isolated event.” In the first round of the 2021 presidential elections, the Republican Party’s candidate José Antonio Kast took the lead. “The right has polarized the country,” she said, and it has defined the center-left government of Boric through “caricatures.” A substantial part of Chile, she says, “feels more represented by the positions of the reactionary right” as a result. “This is not a perfect situation,” Navarrete says, but “we can continue to dispute the issues by being present there.”

No constitution guarantees change

“The democratic exercise that is being carried out with respect to the current constitution is, in itself, better than the way the current one was designed,” Navarrete told me, insisting that although constitutional change is important on the road to social change in Chile, it is not the only route. If the draft of the constitution had been approved in September 2022, the material and governmental situation would have altered, “but that, in itself, does not guarantee the transformation of the country,” says Navarrete.

From her point of view, the results of September reflect a profound disagreement or disconnection between the discussions in the constitutional convention—which wrote the rejected draft—and what the left parties had been proposing for the country. The “disconnection” is linked to the nature of the decade-long protest movement and the social agenda that it had tabled. “We ended up convincing ourselves,” Navarrete says, about the lack of this “disconnection,” which was “a mistake that cost us the [electoral approval]” of the new constitution. The gap between the political parties and the social movements has to be closed since it is these movements, she says, which are “the main engine of any transformation of the country.”

Against ‘denialism’

The Communist Party of Chile is 111 years old. It is part of the government of Boric. This is the fourth time the party is in government; one of the previous times was during the Popular Unity government of President Salvador Allende (1970-73). As Chile goes into a period of commemoration for the 50th anniversary of the coup, Navarrete notes that this would be a good time to reflect on reparations, justice, and a commitment to never return to dictatorship.

The situation in Chile is “fragile,” she says, because there is a growth of “denialism,” the view that nothing really bad happened during the coup and the dictatorship. Laws against denialism have been rejected by the Chilean parliament. “We cannot allow [this discourse] to advance and consolidate,” says Navarrete. “As a government, we have a profound responsibility not to romanticize memory or democracy per se, but to value them as the best conditions for developing politics and making the changes that are needed for those most in need.”

On May 28, Luis Silva, an elected constitutional council member and a member of the Republican Party, declared during an interview with Icare TV that at this historic moment, “a slightly more considered reading” of Augusto Pinochet’s government should be made. “He was a man who knew how to lead the state.”

Regarding these statements, Navarrete alleges that “the right wing believes that based on freedom of expression, all opinions are equally valid.” In contrast, she says, “There is no justification for a genocide of which we were victims as a country and thousands of families. There are people who are still searching for their loved ones.”

Taroa Zúñiga Silva is a writing fellow and the Spanish media coordinator for Globetrotter. She is the co-editor with Giordana García Sojo of Venezuela, Vórtice de la Guerra del Siglo XXI (2020). She is a member of the coordinating committee of Argos: International Observatory on Migration and Human Rights and is a member of the Mecha Cooperativa, a project of the Ejército Comunicacional de Liberación.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.