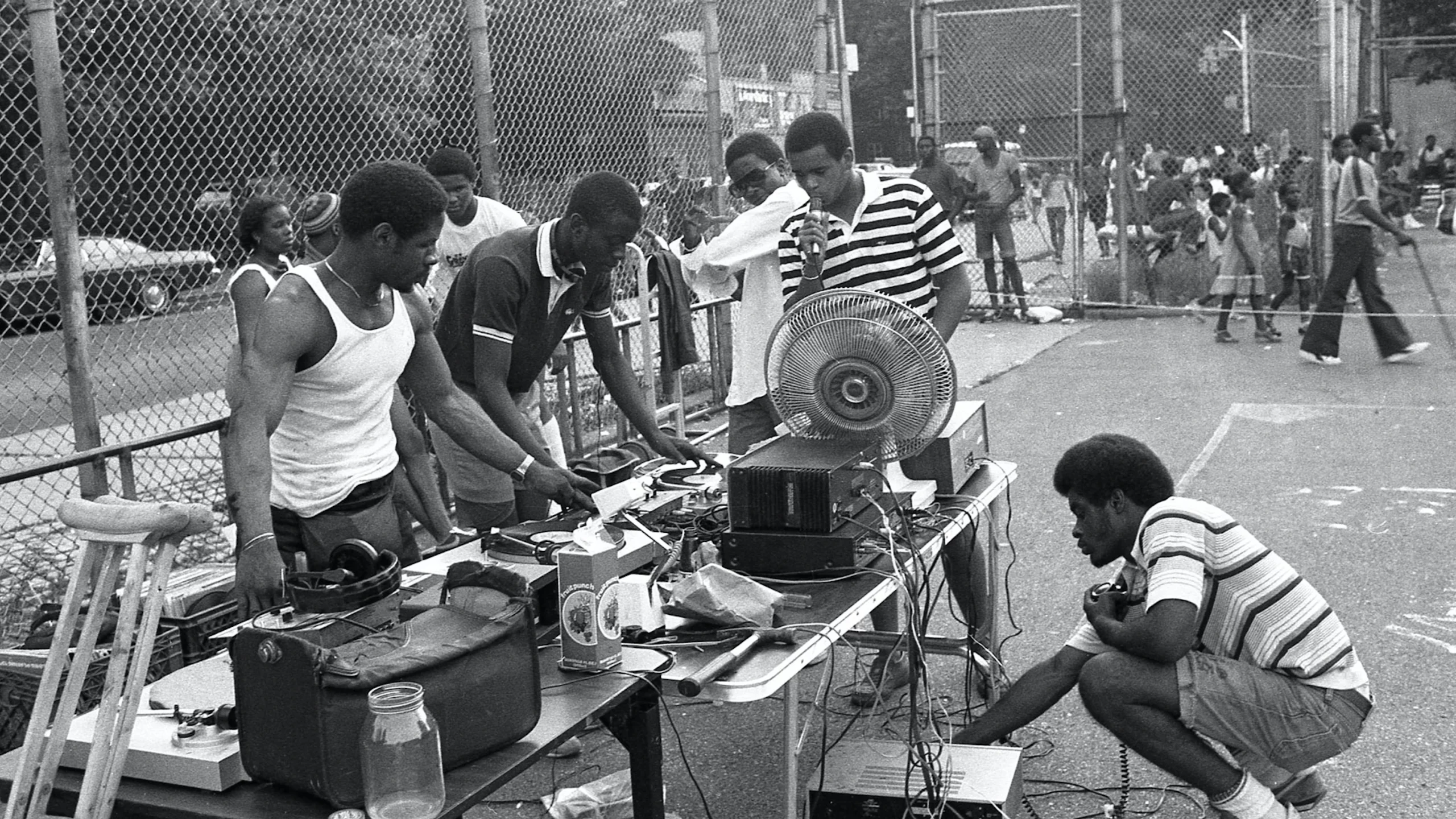

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the “birth of hip-hop” on August 11, 1973 a somewhat mythological date which marks when DJ Kool Herc held a “jam” in the rec room of the 1520 Sedgwick Ave apartment building (located in the Bronx, New York) for his sister’s back to school party. At the “jam” DJ Kool Herc used a turntable to extend the instrumental beat so that people could dance for longer, rapping over the extended beat. According to many, this signaled the birth of hip hop, a genre that would extend beyond music and extend into visual art, dance, language, politics, and every element of culture. Today, hip hop is a global phenomenon, an artform practiced in the mountains of Nepal to the fields of rural China, in the islands of Cape Verde, and to almost every corner of every continent. Often hip hop is the first thing that comes to mind around the world when one thinks of popular culture in the United States.

Hip hop is a unique export of the US. It does not carry the same negative connotations as commercialized products such as Coca-Cola, which has depleted the water supply of communities in the Global South, or Nike, which operates sweatshops in the world’s poorest countries. Hip hop has, of course, to a large extent become itself a commercialized product. But its origins are rooted in the desperate cries of some of the most oppressed communities in the country, and now, throughout the entire world, that legacy is carried on today.

The legacy of state repression

Although it is impossible to pinpoint an exact date for the birth of an entire genre, 1973 in the Bronx was a unique turning point in the economic history of the United States. The previous two decades had seen the beginning of the precipitous decline in union membership in the country from its peak in 1954. The 50s and 60s had also seen the rise of some of the largest social movements in the country’s history—the women’s movement, the Civil Rights movement, the Black liberation movement, the gay rights movement, the Puerto Rican independence movement, and many more. The late 60s and early 70s had also seen the attempted annihilation of those movements, through methods such as the strategic assassinations of political leaders such as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and Fred Hampton. Much of the US working class entered the early 1970s cut off from its political leadership.

Another way in which the actions of the state destabilized social movements was through incarceration. Many other social movement leaders, such as Mumia Abu-Jamal, Jamil Abdullah al-Amin, and Leonard Peltier, became political prisoners when they were arrested on widely disputed charges in later years. One of the most well-known ex-political prisoners (now escaped) is Assata Shakur of the Black Liberation Army, aunt to Tupac Shakur, one of the most famous rappers of all time.

In 1971, US President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs,” in which the state’s apparatus of policing was used to jail poor people specifically for drug offenses. As a result, the male incarceration rate skyrocketed in the 1980s, generating the epidemic of mass incarceration that we see today. Crack cocaine, the drug of choice for the poor and oppressed, was heavily criminalized, while the much more expensive powder cocaine was not. From the late 1980s onwards, drug offenses became the largest increase in the amount of people incarcerated. The Black community was hit especially hard by the drug war.

One of the most influential rap songs in the genre, N.W.A.’s “F-ck tha Police,” released in 1988, is a raw description of the realities of mass incarceration in the Black community. “F-ck the police comin’ straight from the underground/A young n— got it bad ’cause I’m brown,” read the first two lines. The song continues to describe the criminalization of drugs and its connection to structural racism: “Searchin’ my car, lookin’ for the product/Thinkin’ every n— is sellin’ narcotics”

The 1993 song “Sound of da Police,” by Bronx rapper KRS-One, possibly refers to the scandal of the US government’s role in trafficking crack cocaine into Black neighborhoods: “Policeman come, we bust him out the park/I know this for a fact, you don’t like how I act/You claim I’m sellin’ crack/but you be doin’ that”

Hip hop’s early years were defined by precarity

Hip hop, like every element of culture, is a product of its economic conditions. And as a cultural product of the oppressed, hip hop tells a tale of economic despair.

The precarious economic conditions of the 1970s and 80s marked the earliest era of hip hop. Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, a Bronx-based hip hop group, released their hit song “The Message” in 1982 that captured the neoliberal collapse around them.

So goes the first verse:

“Broken glass everywhere/People pissing on the stairs, you know they just don’t care/I can’t take the smell, can’t take the noise. Got no money to move out, I guess I got no choice/ Rats in the front room, roaches in the back/Junkies in the alley with a baseball bat/I tried to get away, but I couldn’t get far/’Cause a man with a tow truck repossessed my car”

And the chorus quite clearly names the increasingly precarious conditions of the working class: “Don’t push me ’cause I’m close to the edge/I’m trying not to lose my head”

The 1970s inaugurated the era of neoliberalism, which in the US was defined by the movement of manufacturing jobs out of the country and into nations where corporations could pay workers less. These jobs began to decline in the US in 1979.

Productivity had been keeping up with hourly compensation in the workplace up until 1979, when the paths abruptly diverged. Productivity continued to rise as wages stagnated, leaving us where we are today, in which workers are paid less for more work. 1973 also marked an enormous capitalist crisis as an oil embargo by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) caused the price of oil to rise by 400% in the United States.

Neoliberalism was the capitalist response to crisis, says Claudia De La Cruz, a South Bronx native and popular educator. “Capitalists tend to build a lifeboat for themselves. Neoliberalism was the lifeboat for capitalists in that moment.”

The Bronx, which anchored this early era of hip hop, was particularly devastated by the economic era of neoliberalism. Deindustrialization and residential segregation policies led white residents to “flee” the Bronx in droves, taking much of the wealth out of the area. Beginning in 1972, entire neighborhoods in the South Bronx were set on fire by landlords who judged that they could make more money off of the fire insurance money for their properties than by renting them out. Bronx residents were left abandoned in a burned down “war zone”, heavily patrolled by police who often harassed the largely Black and Brown residents.

The Cross-Bronx Expressway, designed by urban planner Robert Moses to facilitate travel into and out of the Bronx, displaced over 1,500 families during its construction in the late 40s and early 50s. The highway contributes to the high rates of asthma in the Bronx, which are three times higher than the national average.

Ice-T’s 1986 classic “6 ‘N the Morning,” one of the earliest “gangster rap” songs, references close encounters with the police, criminality, and conditions of despair. His song tells the story of someone who escapes police time and time again, is locked up for several years, only to return to a community even more devastated than the one he left. Ice-T refers to police battering-rams used during drug raids and crack “rock”: “The batter-rams rolling, rocks are the thing/Life has no meaning and money is king”

The Bronx today still remains the poorest congressional district in the United States, with 60% of residents living below the poverty line according to statistics from 2017. Since the era of neoliberalism, inequality nationally has only increased. But the music that originated from the poor and dispossessed of that New York City neighborhood not only lives on, but thrives in every corner of the globe.