Few leaders in recent history have been so vilified by the great corporate press and its supporters as Fidel Castro. The Commander of the Cuban Revolution is, without a doubt, one of the indispensable figures in the history of the Americas and this explains, in part, the permanent ‘symbolic assassination’ which his figure was and is subjected. On his 97th birthday, it is worthwhile to point out some ideas about Fidel and the significance of this great leader.

The man

Those who have had the good fortune to visit Fidel Castro’s birthplace in the small town of Birán, in the province of Holguín, can get a clear idea of his origins. Without being the son of one of the great landowners of pre-revolutionary Cuba, Fidel was, nevertheless, the son of a family with resources.

His father, a Spanish emigrant, had been able to amass a small fortune and acquire land, which allowed him to support a large family, and guarantee a good standard of living and a good education for his children. This education took Fidel first to Santiago de Cuba, the second most important city in the country, and then to study law in Havana, where he was able to fully integrate himself into his generation’s process of coming of age and political struggle.

As a member of the Orthodox Youth*, with an intrinsic sense of justice, Fidel, like all his generation, deeply lamented the suicide of Eduardo Chibás. The death of the Orthodox leader, drowned by the corruption and rottenness of the Authentic Party governments, was a formidable and almost disheartening blow for a youth formed in the failure of the revolution of 1930 and who saw how the yearnings of redemption and national reform were slipping through their fingers.

Batista’s coup d’état in March 1952 seemed to be the final sentence. The military and the barracks returned to impose themselves on the destiny of the nation. And they did so in the service of the interests of big North American capital. Batista was, once again, the hard man who would reestablish order and security. Under his rule, gangster confrontations, hired assassinations, and assaults would end. The army would ensure the necessary tranquility so that North American money, including that of the mafia, could carry out its “business as usual”.

In the process, all freedom would be limited and all opposition violently silenced. The gains of the 1940 Constitution were lost.

The difference is that the generation that emerged in those years and entered political life, especially its most revolutionary wing, was not willing to accept that order of things. Fidel was the natural leader of that process of rebellion. He was the one who captained the audacious assault on the Moncada, which, although a failure, demonstrated two fundamental things: the bloodthirsty brutality of Batista’s regime, which persecuted and massacred the survivors of the action, and the existence of a spirit of rebellion willing to fight for a better Cuba.

That spirit was not crushed by prison, exile or defeat. In his plea of self-defense, later known as “History will absolve me,” Fidel made clear the claims of social justice and sovereignty that were at the base of the whole revolutionary movement.

Chance, which also plays a role in history, determined his survival in very difficult conditions, after the assault on Moncada, in the defeat of Alegría de Pío, in the numerous bombings and combats in the Sierra (his recklessness was such that after the combat of El Uvero, Che and several officers wrote him a letter asking him not to expose himself unnecessarily), the more than 600 attacks against him.

His intellectual level, his political lucidity of not allowing himself to be dragged into any of the pacts and lobbies that were forged around him on numerous occasions, his military capabilities and then his gifts as a popular leader when the Revolution triumphed, made him the undisputed leader of the process and the expression of the aspirations of an entire people.

The politician

As a politician, Fidel knew how to overcome very complex scenarios. The triumph of the Revolution also marked the beginning of an unprecedented escalation of aggression against Cuba. The existence of a triumphant Revolution in a continent that was its backyard was inadmissible for the US. A Revolution that dismantled the dogmas of the right and the left, demonstrating that it was possible to win against a professional army with a guerrilla group inferior in numbers and weapons, and further, that it was also possible to do so from a small neocolonial country, without great natural resources.

This Revolution had to overcome internally the more or less open aggression of the large and medium national bourgeoisie, which manifested itself both in the form of blackmail and aggression of different kinds. Armed groups, financed and trained by the US and the Creole oligarchies, proliferated in various regions of the country, sowing fear and destruction with pirate attacks, sabotage, bombings, assassinations, and robberies. Important figures of the revolutionary government of those early years ended up betraying it by action or omission, including military chiefs such as the first commander of the air force, Diaz Lang (who defected to the US in a stolen plane and regularly returned to drop grenades in central streets of Havana) or Hubert Matos, commander of the military region of Camagüey. The same was the case with the first president of the revolutionary government, Urrutia, the first president of the Central Bank, etc. A good part of the country’s professionals emigrated abroad and even the Catholic Church lent itself to infamous defamation campaigns, such as the infamous Operation Peter Pan.

At the international level, sanctions, threats, and economic blackmail escalated. Persecution and defamation were unleashed by the OAS and several allies of the US. Numerous Latin American countries, under pressure, broke off all kinds of relations with Cuba. In March 1960, the French ship La Coubre exploded in the port of Havana as a result of sabotage, causing the death of almost one hundred people and more than 200 injuries. In April 1961, planes from Honduras bombed several Cuban civilian airports and a few days later 1,500 Cuban mercenaries, armed and trained by the CIA and with the support of the US Navy, disembarked in Playa Girón**, initiating an invasion that was defeated in less than 72 hours and whose prisoners were exchanged with the US government for compotes for children and agricultural machinery.

In 1962, Cuba was involved in the famous Missile Crisis, which was resolved by an agreement between powers leaving Cuba out, which provoked a dignified response from Fidel on behalf of the revolutionary people.

In the midst of that political whirlwind, Fidel knew how to lead and channel the moods and expectations of the people and the members of the revolutionary leadership. He knew how to build the necessary unity among the revolutionary forces and to maneuver firmly on the international scene.

The Revolution was immediately translated into concrete advances: an Agrarian Reform Law that broke the backbone of the large landowning property in the country and gave the land to those who worked it; a massive literacy campaign; health and housing programs, with tens of thousands of scholarships for students at all levels; the creation of a massive system of protection and diffusion of culture that put culture within the reach of the people; and job creation.

Fidel knew how to build hegemony within the process from a dynamic conception of reality, which derived the keys to his political actions from a deep understanding of the various stages he had to go through. He managed to preserve the political autonomy and the particular essences of the Cuban process in his years of greater relationship with the USSR and the socialist camp and, after the collapse in Eastern Europe, he knew how to reconfigure in a very complex scenario the possibility of the existence and permanence of socialism and its achievements in Cuba.

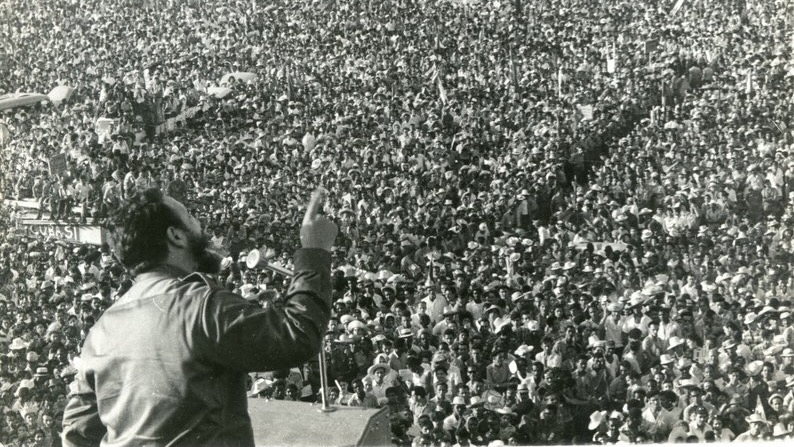

Fidel was also an extraordinarily popular educator, who in long and multitudinous speeches inculcated in the people a new conception of history and the role of Cuba in the Latin American and world scene. Under Fidel’s leadership, Cuba went from being a small sugar-producing island to being a nation that took upon itself the right to expose, denounce, and fight the colonial and neocolonial regime. To support the independence movements of all continents, to send doctors, teachers, sports coaches to all latitudes of the planet. No other nation in the western hemisphere has deployed such a broad and generous international activity. Fidel’s political leadership demonstrated to the Cuban people that they could leap far beyond their own stature, that the size of a nation is defined by the heroism and generosity of its women and men, and not by the imposed handicaps of colonialism and underdevelopment.

The symbol

The figure of Fidel embodies the ideals of sovereignty and social justice of a nation and is the expression that it is possible to build a more just and inclusive nation even in the most adverse circumstances. He is also a key factor of unity for the continuity of the Cuban process over time.

To erode his symbolic dimension, they constantly appeal to lies and half-truths. They wallow in possible mistakes, in rumors, in specific episodes of recent history, in opportunistic testimonies. Undoubtedly, as a man and as a politician, he made mistakes, but these also come hand in hand with great successes — key successes for the subsistence, more than 60 years later, of a Revolution like the Cuban one. His human condition sustained his symbolic condition, and his coherence as a man determined to a great extent the dimension of his figure.

His thought, like all living thought, must be subject to a permanent dialogue. Nothing could be more alien to his conception of politics than the immobility of ideas and peoples. At a time when one of the most effective forms of symbolic assassination is mummification or commodification (think of what they tried with Lenin or Che), the duty of revolutionaries everywhere is to debate, discuss, and create.

Marx said that ideas become material power when they take hold of the masses. Fidel lives today, precisely because his symbol remains as proof that it is possible to make a Revolution with the humble, by the humble, and for the humble, and to persist in that endeavor against the hostility and persecution of the greatest imperial power in history.

José Ernesto Novaez Guerrero is a writer, journalist, and researcher from Santa Clara, Cuba. He coordinates the Cuban chapter of the Network of Intellectuals and Artists in Defense of Humanity and he works with several publications inside and outside the island.

* The youth wing of the Orthodox Party, the communist party at the time in Cuba.

** Playa Girón is known in the US context as Bay of Pigs.