The much awaited presidential elections in Libya scheduled for December 24 will most likely be postponed. The uncertainty is exacerbated by external pressures by countries such as the US, who see immediate elections as necessary to end chaos and disunity, despite the fact that these same countries led the military intervention that created said chaos. This uncertainty threatens to derail the United Nation sponsored political process in the country.

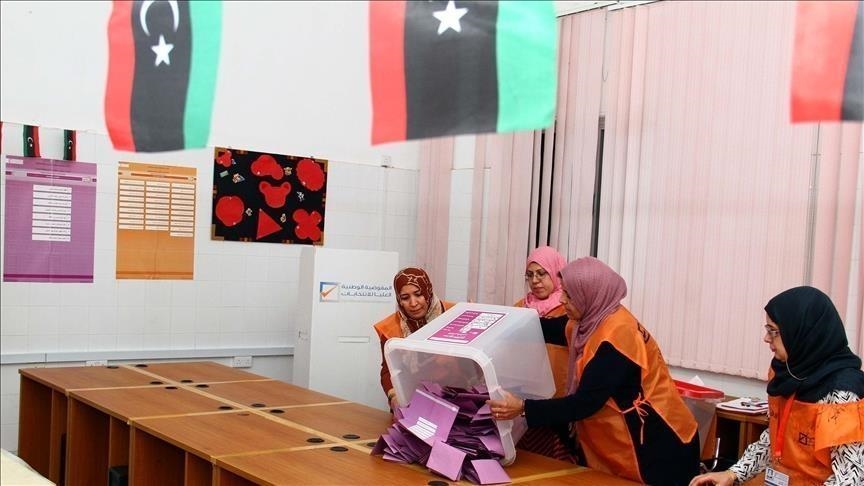

Imad al-Sayeh, head of the High National Election Commission (HNEC) of Libya claimed a few days earlier that all technical preparation necessary to conduct the elections are complete. However, Abu Bakar Marda, a member of HNEC, was quoted by local media on December 17 that the December 24 vote is no longer possible due to political reasons.

In addition to the HNEC’s disunified messaging, the commission has failed to even produce the final list of candidates. None of the 2.5 million voters in the country know who the candidates are. Not one of the candidates who filled a nomination have been canvassing yet and some have even expressed doubts about the process itself. The external pressure is also an attempt to sideline the concerns raised about the impartiality of the institutions, the electoral laws, and presence of foreign troops in the country. If the elections are conducted in the present circumstances, they may meet the fate of the 2014 elections and may prolong the war in the country.

Major Contenders

There are around 100 nominations for the position of president. Although the final list of candidates was to be announced on December 11, it has not been published yet. Among the prominent people who have been nominated are current prime minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah, warlord Khalifa Haftar, son of former leader Muammar Gadaffi, Saif al-Islam, and former speaker of the Libyan parliament in Tobruk, Aguila Saleh.

The HNEC had ruled in November that Saif al-Islam was ineligible to contest the presidential elections on the grounds that he had been allegedly involved in criminal acts. He was sentenced to death by a Tripoli court in 2015 for his alleged role in suppressing the revolt against his father’s rule. He was pardoned later in 2017 but is still wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for his alleged “crimes against humanity”.

Despite Saif al-Islam’s noted absence from the political scene of the country in the last four years since his release from prison, reports indicate he could win the majority of the votes. Saif’s popularity is said to be intact among his father’s loyalists. Due to his non-involvement in the war, Libyans fed up with the decades-long chaos in the country may also prefer his candidacy over Haftar’s.

Khalifa Haftar controlled the majority of territories before the ceasefire in Libya, which may give him some advantage in the votes with a strong base among the warlords in the south and east of the country.

Several observers have pointed out a possibility of indecisive elections, which may lead to rise of less divisive and consensus candidates, with the name of Aguile Saleh doing the rounds.

Major Hurdles

The UN political process created an interim administration in December of last year to prepare Libya for a parliamentary and presidential election. However, the interim government has failed to create the necessary conditions for the conduct of simultaneous elections. Parliamentary elections have already been postponed until January of next year. Given the lack of consensus over the electoral law passed hastily last September by the parliament in Tobruk, and uncertainty around the presidential candidates, it is likely that even if voting happens, the electoral process will lack legitimacy.

There is also a lack of trust in the impartiality of the institutions responsible for major aspects of the elections. For example, the country’s Supreme Judicial Council, tasked with the appeals related to the election process, has complained about interference from the House of Representatives following the Supreme Judicial Council’s refusal to rule out the candidacy of Prime Minister Dbeibah.

Dbeibah, who had promised during the election of the interim administration last year that no member from his administration would contest the national elections, has been accused by Haftar’s loyalists of violating the peace agreement reached last year.

Though the ceasefire agreed upon in October of last year still largely holds, fear of violence between the loyalists of candidates has not subsided completely. Recently several incidents of violent clashes between forces loyal to Khalifa Haftar and the interim government were reported. A large number of foreign troops, including those from Turkey, Chad, Russia and other countries are still in Libya despite the UN and the interim Libyan administration raising the issue and asking for immediate withdrawal.

The resignation of Jan Kubis, head of the UN mission in Libya, and the reinstatement of Stephanie Williams, who had played a major role during last year’s peace process, all barely a month before elections, has contributed to increasing the uncertainty around the electoral process. Kubis was appointed last January primarily to oversee the election.

The external pressure by countries such as the US and France to conduct the elections irrespective of the realities on the ground in Libya betrays the fact that they have not learnt anything from their attempts to impose democracy in countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan.