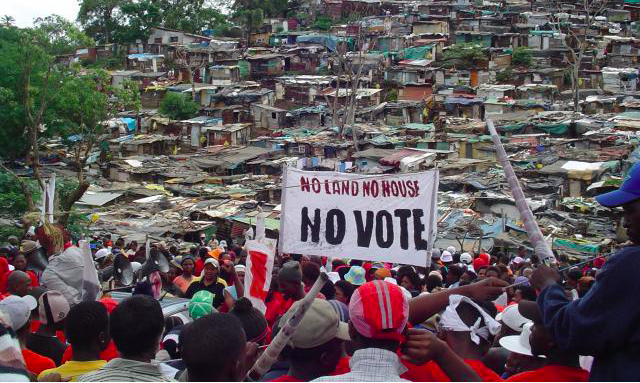

In the face of police brutality, targeted assassinations, death threats and criminalization, the shack-dwellers movement of South Africa – known locally as Abahlali baseMjondolo – has been at the forefront of pursuing the unfinished task of correcting the ills of the apartheid state, at the core of which is the land-question.

Apartheid South Africa, as a matter of policy, had ensured that the land in the prosperous economic heartland of the country was under the control of Whites, while Blacks were increasingly evicted and crammed into poorly planned peripheries, without rights and without the most basic of services like sanitation, electricity, etc.

The African National Congress (ANC), having fought against the apartheid state, came into power in 1994 under the leadership of Nelson Mandela. The ANC promised the “right to adequate housing” – a right that was enshrined in South Africa’s constitution, for it was understood that the spatial divide and land inequities that were engineered over decades by the apartheid state would not automatically wither away with the collapse of the regime. In order to achieve this end through state intervention, a provision was made in the new constitution for the state to expropriate land for redistribution without compensation.

However, over two decades after the post-apartheid regime was replaced with a democratically elected one, 13.5% of the households in the country as of 2016 continued to live in informal dwellings for which the government made no provision for supply of electricity, sanitation, etc. In metropolitan areas, the figure was even higher, at 18.6%.

While much has been done to break the racial feature of the inequities engineered by the apartheid policy, inequality in access to land and, therefore, to housing and food security remains rampant. “The feeble land reform that the ANC did provide mostly conformed to a neo-apartheid logic in the sense that it was predominantly built in desolate places far from urban life and opportunity,” stated this month’s dossier by the Tricontinental Institute of Social Research.

“The land question, which has been vigorously raised in elite politics in recent times, has often been assumed to be a rural question.. But it is in the cities where there has been sustained conflict between impoverished people and the state, as well as private landowners,” the dossier adds.

The shack-dwellers movement has been on the forefront in this fight for dignified housing with the essential basic services – close to or well-connected with urban areas where opportunities for households to prosper exist. The members occupy unused lands and build houses, schools and churches, mostly using materials and manpower that the movement can muster, without being dependent on the government.

While the state has a free-housing programme for the poor, “that scheme is often monopolised by politicians. You’ve got to pay bribes to get those homes. You’ve got to be very close to the local politicians in order to be put in to a list of people for those houses. At times, women have to undergo sexual harassment in exchange for getting on to the housing list. There is a lot of corruption in housing allocation. There was no clear plan or policy on the side of the cities as to who gets the housing and how. If there were to be policy, it would not be followed,” S’bu Zikode, one of the founders of movement, told the Tricontinental Institute in a detailed interview in which he explained about the movement, its origin, its modus operandi, and the enormous challenges its members are facing.

Under such circumstances, in which unused land is abundant but housing is scarce, Zikode said, “We don’t wait for policy makers or politicians. We occupy vacant, unused land as a way to correct the imbalances of the past, because we find it very senseless to continue talking about landlessness when we know there is plenty of land. And we have decided to occupy land.”

Describing the dwellings the movement’s members build to house the poor on the land they thus occupy, he said, “No matter what you call it – slum, squalid conditions, shacks, shanty town – it is what we can afford. We call it home. We have developed our homes. We have had to connect to water and electricity ourselves. We build roads on our own, because it’s all we can do. We always say, when the government is busy building for the elites elsewhere, we will do what we can with the means that we have.”

“We tell comrades from the onset that when they sign up to join Abahlali, they could die”

These accomplishments of the movement have not come without a price. The armed police often use force to evict people in such occupations and injure residents. The dwellings built over days by the movement, by summoning on its own the materials and labour required for it, are razed down to the ground by armed personnel in a matter of hours. Many of its members have been assassinated by hired hitmen and many more attacked, threatened and even killed at protests and evictions by the police and “anti-land invasion units”. A number of them have received death threats and cannot move around freely without caution. Further, the entire movement has been labelled as “criminal” by many government officials.

“Everyone who joins our struggle accepts this risk. And we tell comrades from the onset that when they sign up to join Abahlali, they could die. We have buried comrades. We continue to bury comrades. Comrades continue to take the risk because they do not want what is otherwise their fate – to die slowly, but surely, to die without dignity.. We move from funeral to funeral. We bury our comrades with the dignity that they were denied in life,” said Zikode, who himself was underground for safety after threat to his life was confirmed by the police.

“The hit to carry out my assassination was confirmed. The person who was hired to carry out the assassination was named,” he said, recounting his harrowing experience. While the people who claimed to be from the police department were the ones who informed him about this threat, weeks later, it emerged that the very same people might be the hitmen, suspectedly hired by the Mayor of Durban who had publicly threatened him. According to Zikode, even though all the details of the assassination plot were known, the state took no real measures to offer him protection, forcing him to go underground.

“In two months,” he said, “the movement was infiltrated. We found that trusted comrades were working for our adversaries. I found myself surrounded by a bunch of criminals, including the police.. [who knew] where I live, where I work, my movements. I was totally vulnerable.. I was shivering, seeing that death was imminent. I could not sleep. I was lonely, also knowing that my own comrades that are close to me are working for the enemy. The very same security agencies that are meant to protect me can do harm to me. I was in the shadow of death.”

To endure in face of such dangers, the structure of the organization and the nature of political education has been crucial

Despite such odds, the movement has not only survived, but thrived, with over 50,000 members in Durban, and branches in more than 40 occupations as of April this year. This endurance of the movement has taken more than individual heroism of its leaders.

A number of checks have been put in place to ensure that the leadership cannot subjugate the movement to its own ends. “Our movement,” stated Zikode, “belongs to its members: people who are elected into positions of leadership are there to obey the membership. Leaders who do not obey the membership can be recalled by a decision taken in a general assembly.”

This structure, which holds the leadership accountable to the members, has kept the movement from being hijacked. Whenever the leadership is infiltrated or has lost its way, seeking to use the movement for its own end – be it money or power – the “membership acts to recover Abahlali from them.. I have always said that Abahlali is like the waves in the sea,” he pointed out. “Just as waves reject any trash you put in, Abahlali has always been able to toss out its trash.”

The mechanism to avoid individualist tendencies or lack of community engagement among potential members has been equally crucial. Explaining how new members are recruited into the movement, Zikode said, “We discourage people from joining Abahlali as individuals – it doesn’t help us, and it doesn’t help them either. So, you will invite us to your community and you organise your community before you become a part of Abahlali. And then, once we make our presentation, we leave the community to engage amongst itself and to decide whether or not they want to join Abahlali as a block. One person signing up to Abahlali membership is not going to make a difference when people are facing evictions. There must be a minimum of fifty members signing to Abahlali. We do not rush to sign members up. It takes a month or even years to join our movement. Democracy can be very slow and often very boring, and we have been very patient to live up to that.”

When at least fifty members in a given area have expressed their willingness to join the movement, “we come back again for what we call political education. There, we talk about people’s rights. We do research prior to going to each place. We want to learn about the troubles faced by that community. We want to find out whether they face evictions and police brutality. We want to learn about the poverty and joblessness. We want our political education to be focused to their needs. We don’t generalize. We must focus on why they wanted to join Abahlali in the first place.”

Careful attention has been paid by the movement to ensure that the nature of political education remains one that is bottom-up, and devoid of political jargons which the homeless people whom the movement mobilizes find difficult to relate to.

“Politics,” he said, “starts with the everyday lives of people. If you start with a debate over capitalism versus communism or socialism, then you confuse people on the ground. What does capitalism have to do with ordinary men and women who are homeless? That question needs to be explained from homelessness outwards. You have to start with homelessness, with the lack of water and the lack of electricity. Then you can explain the system, how the system of private property degrades the lives of the millions to benefit the few. You have to start with what people understand and then build the theory.”

Not losing sight of what remains to be accomplished, Zikode admits that “we may not have been able to build houses for [all] the people – that’s what we want..” However, what the movement has successfully accomplished, he said, is changing the “psychological thinking of people. What is it to be helpless, to be dependent on the State? Because that’s what the state does; in order to control you properly, they will create dependency. We have managed to build trust and solidarity among the poor.”

Gazing at the long road ahead, travelling over which many more comrades will lose their life, liberty and limb, Zikode said, “Our struggle for dignity and for a dignified world is long and it is hard. It will not be achieved overnight. It may take years for us to win the question of land and to win on our other challenges. People will be beaten and even jailed. Lives will be lost. For this long struggle, we have to build the confidence, courage and determination of the masses.”