Among the almost 100,000 prisoners distributed across the 68 prisons in Peru (which have a total capacity of 38,000 inmates) there is absolute despair. Even though there is a lack of agreement over the official figures, the estimates of deaths from COVID-19 in the prisons vary from 10-30, and several hundreds more people infected with the virus. The images from the recent protests in the Castro Castro prison calling for hygienic safety measures and medicine are striking. In the repression of the protest by Peruvian security forces, nine were killed and dozens wounded. The situation remains tense. The announcement claiming that there would be a release of prisoners to alleviate this situation has yet to materialize.

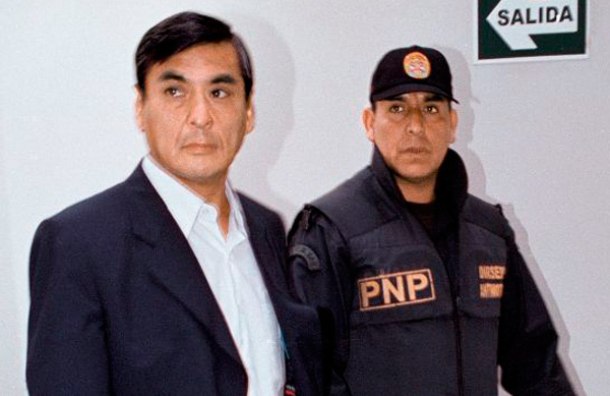

In Lima, there is another prison with special conditions. Located in the Callao Naval Base, it has just 6 prisoners, 5 politicians and Vladimir Montesinos, who was head of intelligence with Fujimori and ordered the construction of this prison facility. One of these political prisoners is Víctor Polay Campos, who has been in isolation for several decades.

The prison located on the Callao Naval Base is called Nemesis, after the goddess of revenge. This is where Víctor Polay, Commander-in-Chief of the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA), a political-military organization that rose up in arms in the country in the 1980s, has spent 25 of his 28 years of incarceration. In that Base on the Pacific coast, prisoners can be counted with the fingers on one hand and visits are carefully controlled.

Close friend of Polay: I arrive hurriedly from everyday business, a fast car has crossed the poorest and most violent neighborhoods of the port of Callao. After forty-five minutes I’m in front of a checkpoint made up of two marines armed with weapons, who are blocking the entrance. From then on there is a great tension in the air. Uniformed and armed navy officers, as well as armed and uniforms agents are everywhere. I have to present and explain the reason for my presence to all the personnel I meet, several roadblocks on the way… Silently and calmly I accept everything, I know that soon after I will see Víctor.

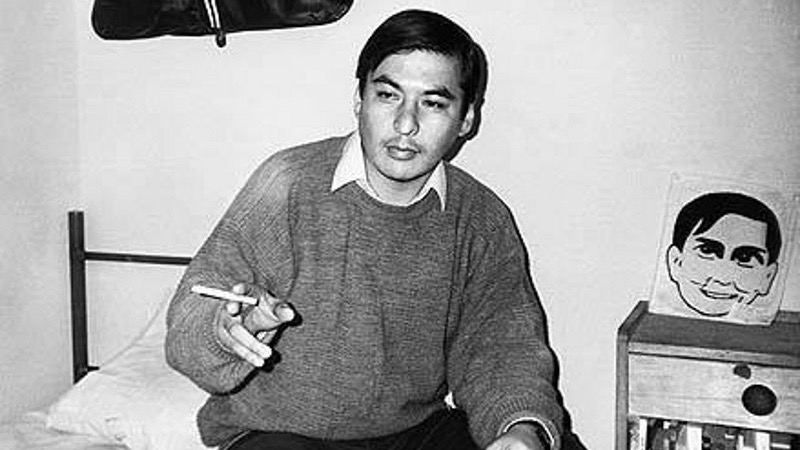

Born in Callao on April 6, 1951, Víctor Polay Campos comes from a prominent family who were founders of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (ARPA), one of the oldest political parties in Peru. He was active in the ARPA party during his childhood and youth. In 1972, he was arrested for the first time and was accused of participating in activities against the military dictatorship by the Police Force. On that occasion, he was held for a few months in the Lurigancho Prison, located in one of the most populated neighborhoods in Latin America with almost one and a half million inhabitants. Today, this prison located just one kilometer from Castro Castro, is the most overcrowded in the country. Prisoners peacefully protest from the top of the pavilions demanding the right to life. “We don’t want to die,” “We want the Covid tests.” Peru is currently the country with the second highest number of infections in Latin America, only behind Brazil.

After being released, Víctor traveled to Spain and France to study Sociology and Political Economy at the Complutense University of Madrid and at the Sorbonne in Paris. While in Europe he left the APRA and joined the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR). He returned to Peru five years later where his commitment and revolutionary political militancy led him to join the MRTA.

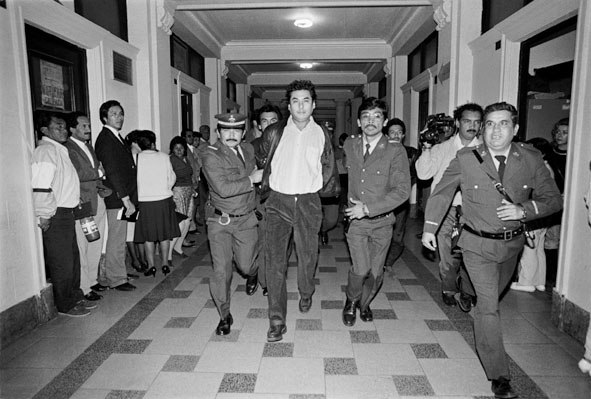

In 1989, he was detained in the Andean city of Huancayo, adding to the group of MRTA prisoners and entered the Canto Grande Prison, considered the first prison of modern maximum security in the country. From the first minute of being locked up Victor and the other MRTA prisoners organized an escape. Emulating the celebrated escapes of the Tupamaros in Montevideo and from the San Carlos Prison in Venezuela, some 47 comrades participated in the famous tunnel escape, built from outside in, in 1990 to continue the activities of the movement. Only two years later Victor was captured again and imprisoned in the Yanamayo Prison in the altiplano region, at 4,000 meters above-sea level. This arrest coincided with the self-coup of Fujimori, who dissolved Congress to intervene in the judicial power and establish a dictatorship that violated all human rights.

Víctor Polay: Before leaving the Yanamayo Prison, we were tortured (to make us put our heads down like they would do to bulls before it goes into the ring) and they put striped uniforms on us. During the journey they threatened to throw me out of the plane, an order from Fujimori. However, during the whole transfer process we never stopped our resistance and our protest.

Once at the Naval Base they took away all of our things and clothing. They gave us a jumpsuit along with two pairs of socks and two pairs of underwear. We did not have contact with anyone and they fed us through a small window. The treatment was aggressive and arrogant. The personnel were hooded and masked.

For more than a year, Víctor was completely isolated, without seeing or speaking to anybody. His family was able to visit him in May 1994. He lived in a state of suspense, with permanent fear, unable to shed the possibility that one morning they would take him out with weapons.

Víctor Polay: The regimen in Nemesis for the leaders of the MRTA was of “silence and reflection” until the fall of the dictatorship at the end of 2000, it was very cruel and inhumane. Unlike the leaders senderistas (people from the Shining Path), that spent the day together and had a series of privileges supposedly because of the “peace agreements,” we were isolated, we went out to the patio alone for 10 minutes and we could not see each other. We did all of our activities alone, we did not have access to books, magazines, newspapers, radio or television. We did not even have a mirror to look at ourselves, nor a watch to know the time. We did not have a calendar to know what day it was. The family visits were just thirty minutes once a month and with the commander right next to us.

And until the end of the dictatorship, no changes were made. For more than 10 years they were kept under very poor conditions of confinement. Today, direct family members can share three hours a week with Víctor. However, the regime of isolation where they live has not changed. A sort of monstrous eternity pressures and retains them.

Close friend of Víctor: I am in what they call the CEREC, Center of Reclusion of Callao. A building with high walls and fences, surrounded by barbed wire in the middle of nowhere, within the Callao Naval Base. No one knows exactly where it is, because all of the visitors go in a completely closed vehicle. As long as we get out of the vehicle, I do not care about the hours that I wait, the ambulance that transports us, completely shut and suffocating. The arrogant treatment the officials give us after a meticulous search. But none of this matters if I am going to see you [Víctor], if I will speak to you for three hours a week. In this infinite time we will feel joy, in these windowless two square meters, with little ventilation and the captors listening to everything.

With so much accumulated silence and so much time in the wrinkles of the skin, Nemesis wants the prisoners to lose themselves. The resistance that the human being is capable of is surprising.

Víctor Polay: We, the leaders of MRTA that were in these conditions, never gave up, and we were never willing to sign anything supporting the dictatorship. In 1998, when we heard that some youth had broken the spell of fear and mobilized on the streets, we began a hunger strike which lasted 30 days, with the objective of making the message heard that, from the place most controlled by repression, it was possible to resist and fight.

In the current context, the COVID-19 crisis adds to a situation of vulnerability of the thousands of incarcerated people in Peru and the world.

With all visits suspended, the solitude on the Base is total. The old times have come back in the new ones. Family members of the prisoners are overwhelmed with fear since March 16 when the quarantine period began.

Close friend of Víctor: Now death is so near. Day after day we see in the news, streets, hospitals and prisons that the number of dead because of the pandemic continues to rise. I am filled with anxiety and anguish and I wonder how you are in this freezing and far-off place, where one time they threatened you with death, placing two coffins at the door of your cell. How is your life these days, are you really safe? Throughout the years, when I did not see you because of the captivity I was sure that our eyes would meet again, but now I experience this confinement with distress and only our weekly call calms me down. Hearing your voice on the other end.

Víctor has been spared of death on many occasions. Now that the virus is spreading across the world, hopefully in Némesis they will be safe.

*Names have been omitted.

**This is the second article of the series Criminalization and punishment in quarantine, a communications initiative of different international media projects whose objective is to raise awareness to, amid the current public health crisis, the realities of those people that are subjected to forced isolation (penitentiary, psychiatric, or migrant detention). The oblivion and exclusion of these populations only increases in these times with the suspension of visits. What is the situation in different countries and what are the responses of the Governments? During these days of quarantine can the confinement of societies be a bridge of solidarity towards the people deprived of their freedom? This series of reports seeks to understand the situation of prisons in times of pandemic.

***Original piece in Spanish by Emilia Igreda.