The hybrid war against Venezuela is intensifying as the US presidential campaign is heating up. The Trump administration and its Venezuelan and international allies have set the stage for an October surprise, a possible attack by the United States or one of its proxies designed to boost President Trump’s reelection. The attacks on Venezuela are coming from multiple dimensions, including overt military pressure, economic pressure, covert operations, and disinformation campaigns. All of these are elements of a hybrid war that has sought to overthrow the government of President Nicolás Maduro over the past years, and each element has seen new developments over the past few weeks, just as Venezuela is battling a surge in COVID-19 cases.

Overt military pressure

The US naval deployment to Venezuela’s maritime border is about to begin its fifth month of operations in the area. Even the few Democrats in Congress willing to criticize Trump’s Venezuela policy have said nothing about this deployment, perhaps because it is entirely normal for the United States to threaten war on a country and then dock its Navy right outside. The silence from Democrats is unfortunate, as this could easily have been used as an example of the Pentagon’s wastefulness. Deploying a massive “counter-narcotics” operation to the Caribbean, when 84% of the cocaine in the US transits through the Pacific, could be low-hanging fruit in the debate to cut military spending.

In Colombia, President Iván Duque met with National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien and Head of US Southern Command Craig Faller on August 18, where they announced the Colombia Growth Initiative, a multi-billion dollar plan that O’Brien says is “focused on rural development, infrastructure expansion, security, and the rule of law,” though the announcement was short on details. Two days after the visit with US officials, Duque baselessly accused Venezuela of trying to acquire medium and long-range missiles from Iran. Both Iran and Venezuela denied the allegations.

On August 27, a Colombian court authorized a US military unit to restart its “advising mission” after previously suspending such cooperation in light of a constitutional challenge with regards to the deployment of foreign troops on Colombian soil. This unit, a Special Forces Assistance Brigade, is designed to “build a professional military force.” It’s worth noting that in his tell-all book, former National Security Advisor John Bolton claims to have learned in February 2019 that Colombia’s “troops simply weren’t ready for conventional conflict with Maduro’s armed forces.”

Venezuela’s southern neighbor, Brazil, is also involved in the escalation. The Brazilian Air Force is holding military exercises between August 17 and September 4. The exercises, which were reported as training for non-conventional combat against insurgent or paramilitary forces, include Black Hawk helicopters and fighter jets.

Brazil and Colombia cooperate closely on military matters with the United States. In a July event in Miami, President Trump was introduced to Brigadier General Juan Carlos Correa of Colombia and Major General David of Brazil by Admiral Faller, who said the men “work for [him].” Former Brazilian President Lula da Silva expressed alarm that his country’s military “may be used for actions incompatible with constitutional principles of non-intervention and self-determination of peoples.”

Economic pressure

On the economic front, the United States seized two tankers of fuel purchased by Venezuela on August 14. This brazen act of piracy didn’t get much attention in the mainstream media, but is part of the strategy to suffocate Venezuela’s economy, which is facing gasoline shortages due to the difficulty in importing necessary chemical additives and spare parts for refineries. Now, the Trump administration is considering ending a sanctions exemption of diesel-for-crude swaps that oil companies Reliance, Repsoil and Eni have been carrying out with Venezuela. Sanctions on diesel would have widespread impacts on Venezuela agriculture, transportation, health and energy industries. Trucks used for shipping food and buses that transport people both depend on diesel fuel. Hospitals throughout the country rely on backup diesel generators to weather erratic electricity supplies. In western Venezuela, diesel is commonly used in power plants for local electricity generation.

The diesel exemption is set to end in early November, and the Trump administration has told the companies to wind down such swaps, prompting criticism from prominent members of Venezuela’s opposition, including economist Francisco Rodríguez, who characterized it as a “clearly electoral measure” that “will cost lives.” Sanctions are becoming one of the main drivers of division within the opposition, as more and more opposition figures have begun to criticize them for not leading to regime change and for punishing ordinary Venezuelans.

Covert operations and criminal disorder

Although we may never know the extent of US involvement in the August 2018 assassination attempt on President Maduro, the March 2019 cyberattack on Venezuela’s power grid, or the May 2020 attempted incursion by two ex-Green Berets and other mercenaries, it would be disingenuous to think that US intelligence agencies and special forces are sitting idle. In Venezuela, there’s growing concern that several crimes over the past weeks are part of a plot to sow chaos.

There is no way to confirm that theory, but it is not far-fetched. Military analyst Frank G. Hoffman states that hybrid war can “incorporate a range of different modes of warfare, including conventional capabilities, irregular tactics and formations, terrorist acts including indiscriminate violence and coercion, and criminal disorder [emphasis added].” An example of this occurred during the weekend of the May incursion, when there was an outbreak of gang violence in Petare, Venezuela’s largest slum. One of the captured mercenaries later alleged that the Drug Enforcement Agency had “paid for gunfire” to act as a smokescreen for the incursion.

The current concern is a series of crimes that began on August 8th with the disappearance of an iconic revolutionary leader. This was followed by the August 20th death of well-known leftist artist under mysterious circumstances and the August 21st murder by police of two leftist communciations workers. Authorities continue to investigate all three cases; in the latter, eight police officers and a district attorney have been charged for the murder and attempted coverup. Attorney General Tarek Saab called the nine people charged “infiltrators” who had entered the police force to engage in crime. Regardless of whether these events are connected to a plot to generate criminal disorder, they are certainly causing psychological harm to the Venezuelan people.

In addition to these crimes, there have been recurrent violent confrontations between the police and well-armed criminal groups. On August 25, a gang equipped with AR-15s, AK-103s and FN-MAG machine guns ambushed a police arms depot. Above, the picture on the left is allegedly of one of the gang’s founders holding a bazooka during the confrontation. Attacks on barracks or arms depots linked to coup plots have occurred several times since 2017, resulting in the theft of assault rifles, heavy weapons, grenades and other explosives that end up in the hands of criminals.

Social media shutdowns

Tech giants appear to be joining in on the Trump administration’s maximum pressure campaign. In March, just as the coronavirus pandemic was beginning in Venezuela, Twitter suspended 40 accounts belonging to officials, state institutions, journalists and influencers, including those of the Health Ministry and Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, who was in charge of the COVID-19 response. Most, but not all, of those accounts were recovered, but Twitter gave no explanation for its actions.

On August 19, Twitter restricted the account of Venezuela Analysis, one of the most important websites for English-language news about the country. As The Grayzone’s Ben Norton notes, these are accounts that “conflict with Washington’s pro-war narrative.” Their suspensions represent an escalation in the media dimension of the hybrid war. On August 21, Google blocked or erased three YouTube and Gmail accounts belonging to Venezuelan state television outlet VTV, preventing Venezuelans from accessing live news and 68,000 videos VTV had uploaded since 2011.

Disinformation campaigns and COVID-19

The timing of these shutdowns is curious, occurring just as a major disinformation campaign about Venezuela’s COVID-19 response is underway. The New York Times and other media outlets have published stories about the plight of returning Venezuelan migrants and the allegedly extreme measures taken by the Venezuelan government to fight the pandemic.

Missing from these articles is the fact that Venezuela has received 130,000 returning migrants since the pandemic began. Venezuela may be the only country in the world that is receiving such vast numbers of people during the pandemic, as most countries have closed their borders and returning home has been difficult for people all over the world. Of those returning Venezuelans, 90,000 have entered through official channels, where they are immediately tested for COVID-19. Most are then sent to a Comprehensive Social Care Point (PASI) to comply with quarantine protocols. At the PASIs, migrants receive food, medical care and personal hygiene products as they wait 2-3 weeks to ensure they are not infected with the coronavirus (positive tests can extend their stays).

The other 40,000 migrants returned to the country through unofficial routes, skipping health and immigration controls. In late May, Venezuela began experiencing rapid growth in COVID-19 cases after controlling the pandemic for two months. Much of this growth was attributed to migrants who did not heed the health warnings; at one point, 80% of Venezuela’s new cases were imported from abroad. In mid-June, the numbers flipped and community transmissions surged rapidly.

There are good reasons for migrants to avoid official entry points, including dismal conditions on the Colombian side of the border and long waits to enter given the limit on the number of people who can cross the border daily. However, many of the migrants have been victims of fake news. Telesur’s Madelein García interviewed a returning Venezuelan who was told in Colombia that Venezuelans were injecting migrants with COVID-19 because doctors were being paid by case numbers, as well as lies about migrants not being fed and being locked in cages in PASIs.

Although there are reports in social media of poor conditions in certain PASIs, they appear to be the exception, rather than the rule. A United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs report noted the differences between the over 200 PASIs, with those in universities and hotels having better infrastructure than those in grade schools and gymnasiums, some of which require “greater support to strengthen their capacity to offer services.” The United Nations and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) have visited PASIs and are contributing aid to the migrants temporarily quarantined in them. Government and local officials routinely inspect PASIs, and Venezuelan media have reported from them. The PASIs have been much maligned in the media without any context of the vastness of the program or the challenge of fighting off a pandemic for a country economically suffocated by sanctions.

The mainstream media narrative around COVID-19 and Venezuela’s migrants is being used to present the country as being in need of humanitarian intervention. Indeed, the Trump administration and think tanks like the Center for Strategic & International Studies, which put out a report titled “Venezuela: Pandemic and Foreign Intervention in a Collapsing Narcostate,” have been attempting to turn Venezuela’s COVID-19 response into an issue of regional security. The Atlantic Council, considered to be NATO’s think tank in Washington, held an event on August 13 with Admiral Faller in which he declared that the Maduro government is an urgent threat to democracy, economic stability and the COVID-19 response.

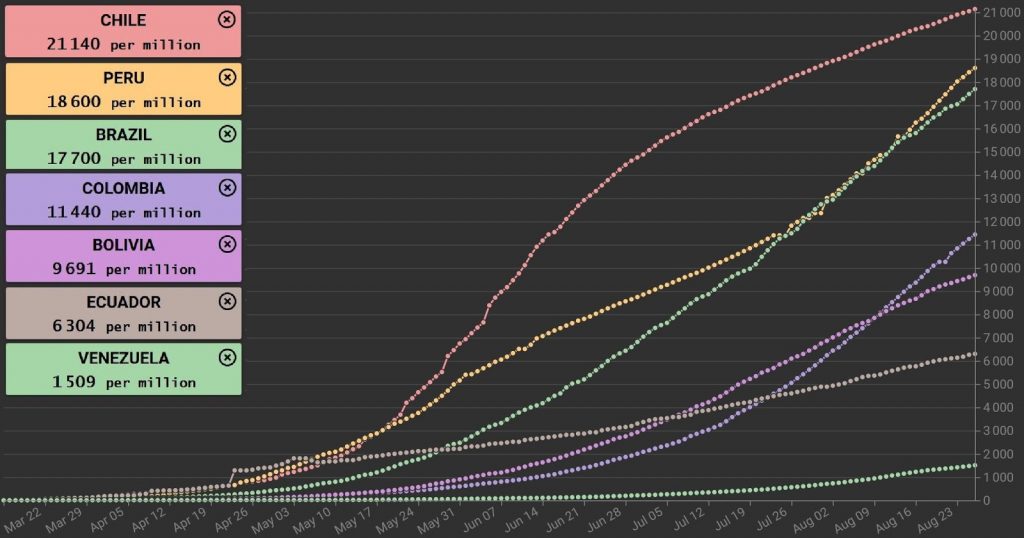

Yet as seen in the graph above, it’s ludicrous to claim that Venezuela is a COVID-19 threat. The country is doing significantly better than its neighbors in controlling both the spread of the disease and the number of casualties. Venezuela has experienced 358 total COVID-19 deaths, a rate of 13 deaths per million population (Argentina is the next lowest in South America, with 180 deaths per million). After a surge in cases from July through mid-August, the curve of new cases looks like it is flattening, although it is still too soon to tell. Venezuela has been able to weather the storm thanks to its policy choices and timely aid from Cuba, China, Russia, the European Union, the ICRC and UN agencies.

Of course, military action against Venezuela would impede, if not destroy, its capacity to deal with the pandemic, which would lead to increased infections in Brazil, Colombia and other nations if there’s a wave of war refugees. Yet these concerns seem secondary to Venezuela hawks, who view a second Trump administration or a Biden administration as less likely to deliver regime change than a pre-electoral attack.

According to sources that spoke to La Política Online, Senator Marco Rubio has been advising the Trump administration that military action against Venezuela would “ensure Florida’s Electoral College votes in November.” It should be noted that these allegations have not been independently verified and Senator Rubio has not commented on them. However, President Trump’s hawkish Venezuela policy is based around winning Florida and many of the events detailed above have been put into motion to give the president the military option he’s been threatening since August 2017. The stage is set for a disastrous October surprise, especially if Trump’s chances for re-election look dim.

Leonardo Flores is a Latin American policy analyst and campaigner with CODEPINK.