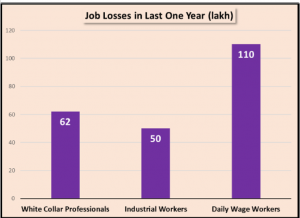

Over 6.2 million white collar professional employees and 5 million industrial workers have been sacked in India the past one year. The former refers to engineers, including software engineers, physicians, teachers, accountants, analysts and other professionally qualified persons employed in private or government organizations. This does not include self-employed professionals, like doctors or lawyers or chartered accountants, etc., in private practice. Industrial workers include all types of industry whether large or small.

But, the biggest job loss has been suffered by daily wage earners, whether rural or urban. Compared with last year, 1.1 crore (11 million) such jobs have been lost by August this year, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) estimated.

This shocking snapshot of India’s recessionary economy emerges from latest data released by CMIE, based on their four-monthly ‘waves’ or household surveys. It covers the period from May to August 2020. [See chart below]

CMIE had earlier reported that about 2.1 crore (21 million) salaried jobs had been lost between August 2019 and 2020. This included not only white-collar professionals and industrial workers but also informal sector services, like cooks, domestic workers, security personnel etc. The break-up of this larger category (‘salaried employees’) has now been released.

A striking feature of this is that the job losses have continued in July and August despite the partial lifting of lockdown restrictions. About 4.8 million salaried jobs were lost in July and another 3.3 million jobs in August.

11 million daily wage earners lost jobs

The CMIE data also shows that employment in farming has gone up from an average of 11 crore (110 million) in 2019-20 to 12.5 crore (125 million) in August 2020, an increase of some 1.4 crore (14 million). But the number of daily wage laborers was still 1.1 crore (11 million) less that the average employment of 12.8 crore (128 million) last year. These are persons who cannot find work anywhere else and are thus forced to do manual labor in construction sites, loading-unloading, seasonal agricultural work or agro-processing jobs, etc. Also included would be a vast number of daily wage workers employed in industrial and private sector jobs who were among the first to be sacked after the lockdown was announced in March. The economic slowdown has severely affected the construction sector and this has caused a big drop in employment.

Two sections that have recovered from the lockdown shock to previous year’s level are: entrepreneurs and white-collar clerical employees (which includes desk job employees like secretaries, BPO/KPO workers, data entry operators, etc). It is possible that work-from-home systems have sustained the lower grade white collar employees, but the contrast to professionals is notable and cannot be explained by that alone.

Entrepreneurs in India should not be confused with their counterparts in richer countries. Their numbers have steadily grown over the years even though unemployment has also grown. This means that these entrepreneurs are mostly self-employed individuals with no other employee, providing services or involved in retail trade.

The shock to India’s economy by the ill-conceived lockdown which started at midnight of March 24-25 this year and lasted for two months before some easing was ordered, appears to have caused longer lasting damage to the economy. Remember, that India’s economy had already slowed down last year, much before the pandemic arose. And now it seems to be continuing on its downward spiral with greater energy.

Who are these sacked industrial workers?

Analysis of other data done by CMIE indicates that the bulk of the industrial workers who lost their jobs may be from medium, small and micro industrial units (MSMEs). Analyzing the quarterly financial statements of 1,300 listed industrial companies, CMIE concluded that inflation adjusted gross value added (GVA) of manufacturing companies declined by 41% in the April-June 2020 quarter, while their real wage bill declined by about 15%. This seems to indicates that employment loss in large industrial companies was much less, or wage freezes were also in effect. Probably, it was a combination of both, with sectoral variation – some industries would have much larger job losses, like FMCG producers, while others may have less, like say fertilizers. This is understandable because there has been a trend of declining household consumer expenditure since last year, which would hit family spending on discretionary items.

So, it is very likely that 50 lakh (5 million) jobs lost in the past year would mostly be from smaller industrial units. The MSME sector has been reeling under a series of shocks – all created by the Narendra Modi government – in the past few years. First was the demonetisation of 2016, then followed the imposition of Goods and Services Tax in 2017. The sector which employs almost two-thirds of the industrial workforce was severely hit by these. It had barely started recovering, when the whole economy started sliding last year. And then came the corona-shock this year, which devastated the sector completely. It has been estimated that almost half the units of this sector may never be able to recover from the lockdown.

Workers from these units also form the bulk of those who lost their jobs in the lockdown period. It is mostly these workers that started the long march to their homes in distant villages during end-March and April-May. The government itself has estimated that about one crore such migrant workers returned home. Many might be finding some days of employment in the rural jobs guarantee scheme (MNREGS) or during the rabi harvest (April-June) and the subsequent kharif sowing. But this is very low-paid transitory work, a far cry from their salaried employment in the industries in cities.

The inability of the Modi government to contain the pandemic and the disastrous economic policies being followed are twin drivers of growing mass discontent in India. The government seems to be banking upon its Hindu nationalist appeal to escort it through this approaching storm, but the severity of this double crisis is unprecedented. Not only is the country in uncharted territory, so is Mr. Modi.