“What is a human right? We are human, but we do not have any rights!” says an Afghan refugee in New Delhi as she narrates the impact of the pandemic on her community and waits for the vaccine. Although the number of people forcibly displaced globally, accounting for 1/7 of the world population, should formally have equal access to healthcare as host populations, the COVID-19 pandemic has once again shown that displaced people have little access to essential care, including vaccines. Only 30% of National Deployment Vaccine Plans (NDVPs) submitted to the COVAX Facility include refugees in their national vaccine programs, and those who do include them often do not extend the same coverage to asylum seekers and undocumented migrants.

Oppressive immigration policies continue in spite of the pandemic

Before the pandemic, 82.4 million people were forcibly displaced. Since 2020, 11.2 million have been newly displaced due to continuous conflicts in Afghanistan, Yemen, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Palestine, Syria, Iraq and the Central African Republic. Communities of migrants, refugees, and displaced people became vulnerable to loss of livelihoods, reduced aid, and stagnation in documentation processes as the pandemic accelerated.

At least 70% of migrants, refugees, and displaced people live with economic, social and legal vulnerabilities resulting in poor health and well-being. COVID-19 has only added to existing problems, as pre-existing medical conditions and limited access to healthcare increased the risk of severe COVID-19 for displaced communities: the infection risk for them is at least twice as high as for a native-born person.

The negative impacts on the social determinants of health, lack of access to quarantine facilities, protective equipment, and water, sanitation and hygiene services, have led to continuous COVID-19 outbreaks in refugee camps. Once vaccines became available, displaced people were left at the end of the line as well.

Globally, 70% of 104 NDVPs reviewed by WHO in 2021 excluded migrants. According to the same study, most plans omitted more than 11.8 million Internally Displaced People (IDPs). This alarming data has not impacted the global leaders; instead, they continue to close the borders and adopt harsh policies to keep asylum seekers away during a pandemic. While the need for healthcare increased, countries like Denmark adopted migration policies that reduced the number of asylum applications from 21,000 to just 1,500 during the pandemic period. Regardless of the health crisis, Australia continues to adopt policies that isolate undocumented migrants in dentition centers.

Exclusion through digitalization

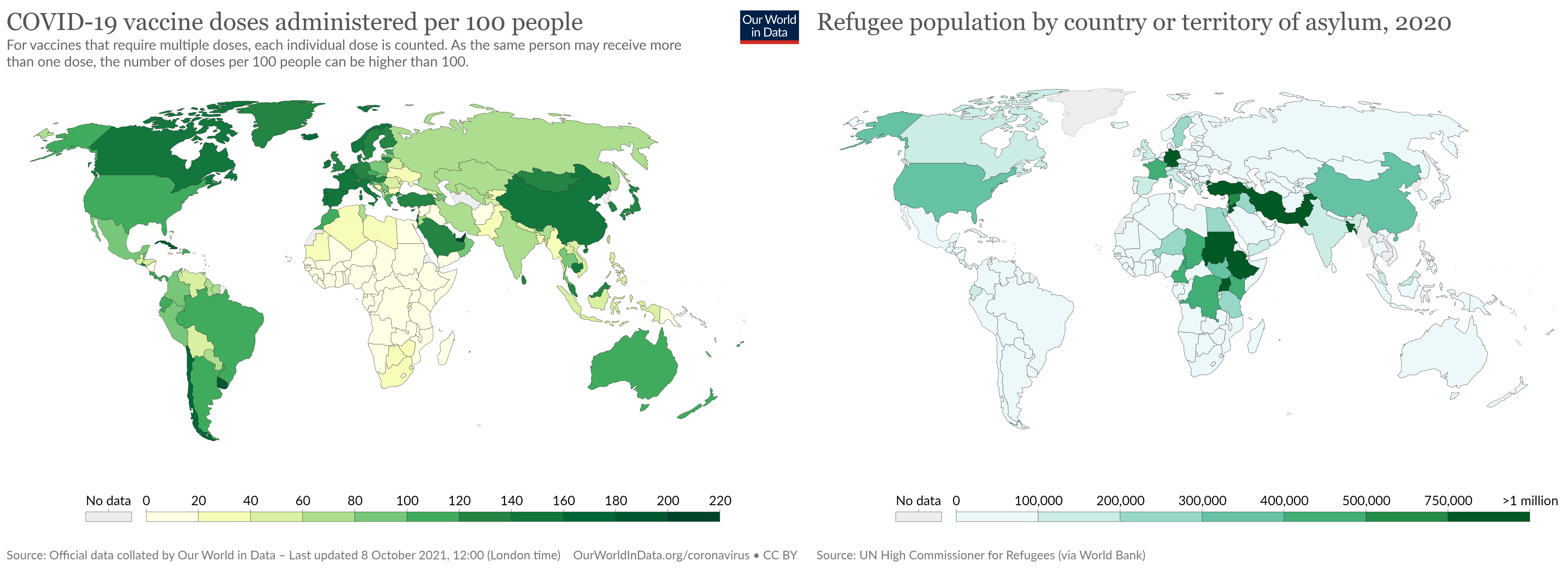

The growing vaccine inequity has resulted in 79% of global vaccine doses being administered in high-income countries compared to only 2.3% in low-income countries. For illustration, Bangladesh, the DRC, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Pakistan, Sudan, Uganda, and Venezuela host 86% of global refugees, but have the least access to even the first dose.

Countries with the highest refugee and asylum populations are among the countries with least administered vaccine doses.

“We are not getting the vaccine. If we apply in government hospitals, we hear no response because we don’t have any local identity cards, and our passports are expired. We cannot afford private hospitals because the cost is very high,” says an unemployed Rohingya refugee in India. Refugees need to constantly prove their identity although they have fled war, violence, or persecution; they often have no identification proof.

Most vaccination programs are digitized and linked to identification proofs which by design exclude people who lack documents. Some refugees shared that identification documents that allow access to health, livelihood and education are even more of a priority than vaccines themselves. Even in cases where vaccines could be accessed despite the lack of papers, migrants and refugees experience difficulties.

The United Kingdom allows refugees to access vaccines through the Public Health Practitioners. Yet, it excludes refugees that fail to provide identification, particularly undocumented migrants. Unfortunately, in many refugee host countries, health service providers are unaware of refugee rights and refuse access to healthcare, including turning people away in vaccination centers.

No trust in the healthcare system

Even in countries with inclusive vaccination programs, most undocumented migrants are hesitant to register due to the fear of penalty, deportation or separation from their families. For example, in the Maldives, the government has agreed, in collaboration with the Red Crescent, not to use vaccine registry data for any other purposes. Still, refugees fear being in public registries more than being infected by COVID-19, as they are concerned about possible implications for their immigration status.

Another set of problems arises when it comes to informing refugees about their rights: 47% of refugees thought they were not eligible for the vaccine or were unaware of any vaccination programs. Though Lebanon and Jordan follow an inclusive vaccine policy, UNHCR highlights that vaccine hesitancy persists among refugees due to misinformation. The hesitancy is also a result of lack of trust in the governments of the host countries. Cultural norms and language barriers add to the refugee hesitancy in accessing the COVID-19 vaccine.

In spite of predominantly exclusive trends when it comes to the vaccination of displaced people, there have been some positive examples too. Despite the challenging economic conditions in the Americas, most countries included refugees in NDVPs. Portugal temporarily granted asylum seekers full citizenship rights during the pandemic to ensure access to healthcare, including vaccines.

But access to vaccines cannot be granted by national vaccine programs alone, nor statements in international forums. In spite of many declarations of solidarity by politicians from the Global North, the hope for vaccinating low-income countries continues to fade as G7 nations block the WTO TRIPS waiver proposal and waste millions of excess doses that are reaching expiration. As highlighted by the PM Mia Mottley of Barbados at the recent UN General Assembly, “How many more variants of COVID-19 must arrive, how many more, before a worldwide action plan for vaccinations will be implemented? How many more deaths must it take before excess vaccines in the possession of the advanced countries of the world will be shared with those who have simply no access to the vaccine?”

Vaccine inequity is a result of long-standing structural inequalities that range beyond the health sector. We need pragmatic and intersecting political solutions that prioritize human rights over power. The world cannot afford to leave one-seventh of its population unimmunised against COVID-19.

Read more articles from the latest edition of the People’s Health Dispatch and subscribe to the newsletter here.

————————

Meenuka Mathew is a teaching and Research Fellow at Jindal School of Government & Public Policy in India