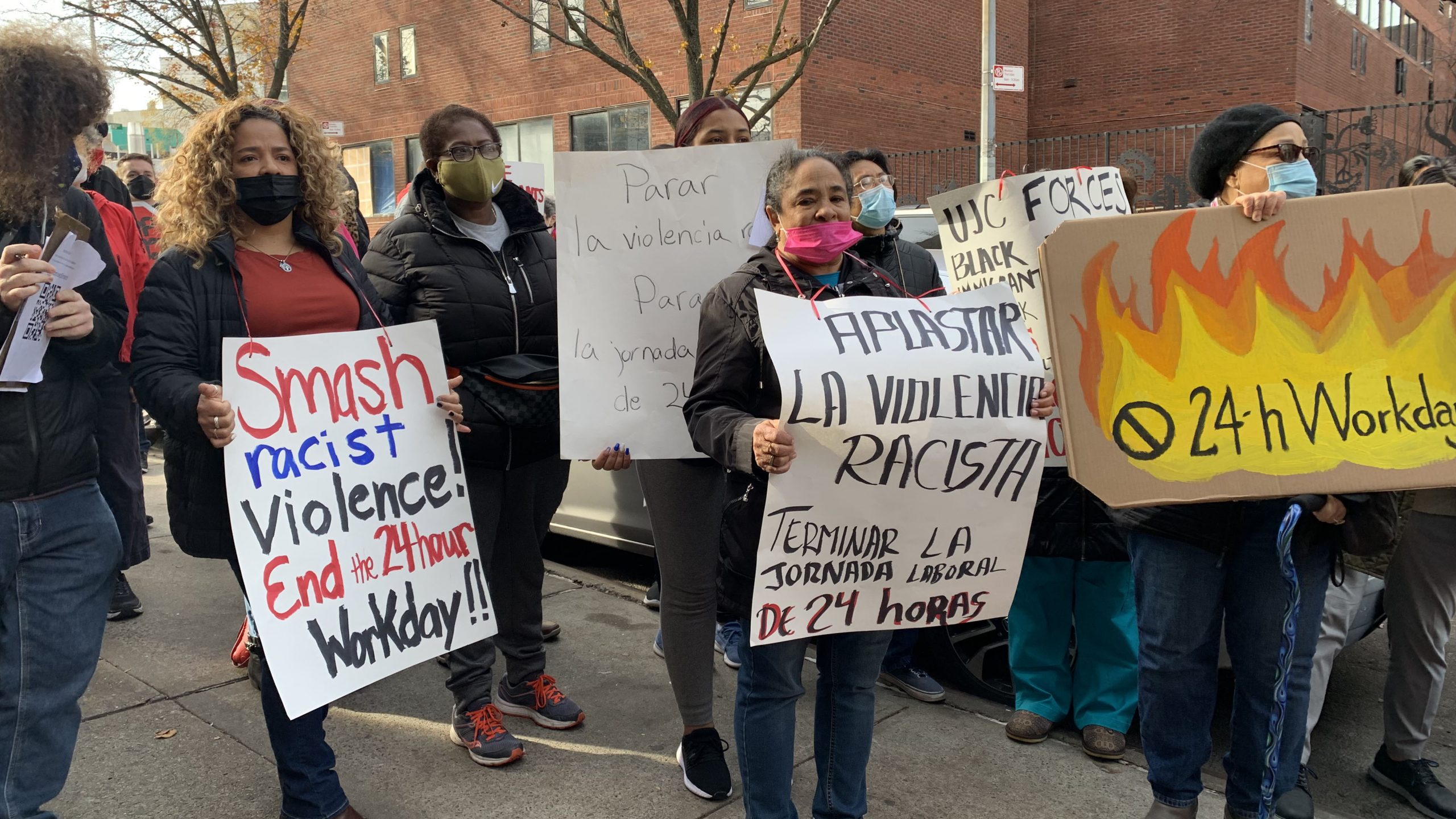

Workers employed with the United Jewish Council (UJC) home care agency rallied to end the 24-hour work day and demand their stolen wages on the morning of December 16. While home care workers in New York are being forced to work 24-hour shifts for poverty wages, 11 hours worth of that pay is stolen by their employers. A coalition of worker’s rights organizations including the Ain’t I A Woman Campaign and the National Mobilization Against Sweatshops (NMASS) have been organizing alongside home care workers for years against these unjust labor practices.

“I am traumatized from working 24-hour shifts,” said Epifania Hichez, who has worked at the UJC for 11 years. “Working 24 hours destroys your life. You lose everything, especially your health. You lose your family also.”

She described how working these long hours can be deadly, “Years of 24-hour shifts killed my friend Ramona. That’s why I say we must end this racist violence of 24 hours. Our lives matter.”

Many workers shared the sentiment that their exploitation and long hours have roots in racist attitudes as the majority are majority Black, Latino and immigrant women.

“UJC thinks that people don’t care about what happens to these home care workers but today there’s such an outpouring of support from the community,” Vicki, an organizer with the Ain’t I A Woman Campaign, told Monica Cruz. She highlighted, “We’re standing here with people of all races, workers of all trades, people who are here to say that the 24-hour work day has got to stop.”

Rally organized for home care workers forced to work 24-hour shifts for days at the United Jewish Council. Most of these workers are Black and Latina and are only being paid for 13 hours. @aiwcampaign pic.twitter.com/UthidN5vxB

— Monica Cruz (@palantemami) December 16, 2021

According to the organizer, “At every turn, UJC has done everything in their power to continue this violent practice. We’ve sent them letters that they’ve ignored, they’ve intimidated workers, and even before this action, they were tearing down our posters. And to us this shows that they’re scared because they know that the violence of the 24-hour shift is unacceptable.”

In 2016, UJC home care workers filed a class-action lawsuit for unpaid wages, including 11 hours of regular and overtime pay. The NY State Court Appellate Division of the First Department ruled that the case could proceed in court, despite attempts by the UJC to block the lawsuit. In 2021, the UJC filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, claiming that its status as a nonprofit exempts it from paying the minimum wage and overtime pay. In September 2021, the Court denied this request.

Regardless of the back and forth in the court, the law is on the employer’s side. New York State labor law currently allows home care workers to work 24 hour shifts while only being paid for 13. Organizers are advocating for a State Assembly bill that would require shifts with patients who need 24-hours of care to be split into two non-sequential 12-hour shifts. They are also supporting a bill in the State Senate that would require overtime to be voluntary.

More than one in seven low-wage workers in New York City is a home care worker. More than half rely on public assistance to get by and one in four live below the federal poverty line. This low pay is causing an understaffing crisis. It’s projected that by 2025, there will be a shortage of 83,000 workers in the city.

This crisis is being seen across the country, as demands for home care services skyrocketed by 46% in 2020. The problem is likely to get worse as, by 2030, the number of Americans who are 65 years or older is projected to outnumber children for the first time in US history. Seven in ten of these elders will need long-term care at some point. Raising wages has been proven to curb turnover rates and improve care.

President Biden’s Build Back Better bill would allot $150 billion to improve pay for low-wage home care workers, plus $1 billion for grants and $20 million for hospice and palliative nursing programs to benefit this essential workforce.

Howard Brandstein of Sixth Street Community Center said, “Home care workers are the ones who take care of our sick and elderly … They deserve to be paid well and not overworked so they can get the rest they need and we can get the best care for our loved ones.”

Monica Cruz is a reporter with US-based media outlet Breakthrough News.