Commercialization trends in the health sector in Kenya have led to obstacles in access to care in Kenya, especially when it comes to poor, marginalized communities, including people living in urban informal settlements. This is the main conclusion of a recent report published by the Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (GI-ESCR) – Patients or Customers? – which looks into experiences of healthcare-seeking Kenyans.

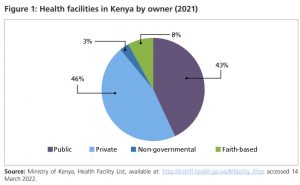

The report shows that investment in public healthcare in the country has been long disregarded in favor of strengthening ties with the private sector, and increasing its presence in the field. This is true for both national and international policies, and has resulted with most health facilities in Kenya being in private ownership.

According to Rossella De Falco, GI-ESCR’s Program Officer on the Right to Health, the propagation of commercialized models of healthcare has impacted standards of care in many ways, starting with the fact that it has diverted investments from the public health system and, consequently, reduced its capacities.

During a report launch in Nairobi, De Falco stressed that such disinvestment in public health care hits marginalized communities the most: less money for public health infrastructure has meant less public health facilities in the proximity of urban informal settlements, forcing people towards the private health sector. “And the private health facilities which are within reach for those living in urban informal settlements are either of low quality and badly monitored or extremely expensive, which means that people think really hard before seeking care,” said De Falco.

Members of the community who took part in the report launch referred to a number of problems that the lack of public health infrastructure caused in their everyday lives. These include inadequate responses to illnesses caused by social and ecological factors, such as living in the proximity of dumpsites. In the settlement of Dandora, life near a dumpsite is the cause of respiratory issues like asthma and eye allergies, but the closest public institutions do not have the capacities or equipment to treat these conditions.

Public hospitals are often starved of essential medicines, so people are forced to look for them in other places and pay for them out of pocket. “We are always told to go and buy elsewhere, and, in most cases, we don’t have the money so we just go back home and pray,” said one of the respondents of the report.

Financial obstacles and lax monitoring of private sector

Financial obstacles are another widespread effect of commercialization that the report identifies. A combination of low health insurance coverage among the marginalized, including the unemployed and informal workers, and requests for upfront cash payments at private health facilities are not only turning people away from the health system, but are also obviously going against World Health Organization (WHO) guidance on financial protection, said De Falco at the launch.

And while this was a problem for many long before the COVID-19 pandemic, the situation got worse as public health facilities were not able to fulfill the need for testing and treating patients. At the beginning of the pandemic, the private sector took over testing services, pricing COVID-19 tests at USD 40-60. Such a price range put tests completely out of reach of poor people, and this influenced both their ability to seek non-COVID-19 care, and participate in other areas of life. As negative tests became a prerequisite for many everyday activities, not being able to present one would reflect on one’s ability to go to work, which would make the existence of many community members even more precarious than before.

Inadequate funding of the public healthcare system has implications for health workers too, says the report. Overall, Kenya records a below-the-average number of nurses and physicians compared to WHO recommendations. In 2018, Kenya had 16 physicians to a 100,000 population, compared to the recommended 21.7 physicians to a 100,000 population. When it comes to nurses, it had 167 nurses – compared to the recommended 228 – to a 100,000 population. The staff shortage became exacerbated by the pandemic, with many health workers reporting being overwhelmed by the influx of patients since March 2020.

“Health workers are a tremendously important part of our health system, and we have to find a way to support them too. We need to find a way to make the health system work for everyone,” said Ravi Ram from the People’s Health Movement (PHM) Kenya during the report launch.

According to the findings of the report, making the system work for everyone would start with making better use of government money, including increasing public investment in health towards the goal of 15% of the national budget from the Abuja Declaration, but would also mean a shift of attention towards purposeful investment in public health care.

Additionally, De Falco pointed out, improvements to the health system would also mean better monitoring of the private health sector and addressing the proliferation of low-quality, low-cost private clinics and pharmacies. This would represent a significant shift away from the current status, where the government’s encouragement of the private sector, in combination with lax implementation of available monitoring mechanisms, exposes low income people to substandard care and undermines their right to health.

Read more articles from the latest edition of the People’s Health Dispatch and subscribe to the newsletter here.