August 19, 2022 marks one year since the brutal assassination of our Comrade Malibongwe Mdazo while he was on organizational duty for the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA). Executed in broad daylight by a hail of bullets, Mdazo died outside the office of the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) in Rustenburg. He had been attending a verification process at the CCMA in pursuit of organizational rights and decent working conditions for mineworkers. A prominent song, chanted loudly in isiXhosa at his funeral in Mqanduli in the Eastern Cape of South Africa said:

Kuyoze kube nini na? (For how long?)

Kuyoze kube nini na, siphila impilo ebuhlungu? (For how long must we live in suffering?)

Khanyisa weMdazo kubemhlophe, siphila impilo ebuhlungu (Mdazo shine light on us so that our path is clear, as we live in suffering)

In remembering Mdazo, we also commemorate ten years since the 2012 Marikana massacre where 34 mineworkers were mercilessly gunned down by the South African Police Service (SAPS) for demanding a living wage. We also observe the anniversary of the 1946 African Mineworkers Union strike which saw 75,000-100,000 mineworkers down tools in the demand for better wages and living conditions. Equally we mark the assassination of Mahlomola Hlothoane, a NUMSA shop steward at Reagetswe contractor in Rustenburg. Murdered in June this year at his home, Mahlomola, like Mdazo, assisted NUMSA in coordinating recruitment and organizing at Impala Platinum Mine (Implats).

Mdazo was a volunteer recruiter for NUMSA in the platinum belt of South Africa’s North West Province. His work included recruiting and organizing workers employed by contractors at Implats. He was attracted to NUMSA on the basis of the Union’s track record and consistent struggle credentials in fighting against exploitation and inhumane working conditions in all sectors it organizes.

Mdazo’s contribution in recruiting and organizing thousands of mineworkers for NUMSA in the platinum belt was rooted in his uncompromising principles and values. He embodied the just demand that workers deserved a living wage and dignified standard of living.

Mineworkers who work in South Africa’s gold, platinum, chrome and diamond mines are recruited through a brutal migrant labor system. Hugh Masekela’s world-renowned song ‘Stimela’ highlights how mineworkers travel by train from the rural hinterlands of Southern Africa – from Mozambique to Zimbabwe, Zambia, Namibia, Swaziland, Lesotho, and beyond. South Africa’s economy is built on the blood and sweat of black and African labor through an arrangement engineered by the colonial, apartheid system of separate development. Stripped of their land and dignity, mineworkers from South Africa’s former Bantustans and throughout the SADC region were forced to look for economic greener pastures in strategic sectors of South Africa’s economy. Working conditions in the belly of the earth are appalling and unsafe, often resulting in permanent illness and even death.

Against this backdrop, Mdazo sought to spread the gospel of NUMSA whose aims and objectives, as enshrined in the Union’s Constitution, include among others championing workers’ rights, democracy, solidarity, and safe working conditions. For Mdazo, these aims were in sync with his commitment to improving and fundamentally transforming the lives of mineworkers. While their sweat and blood produce a plentitude of profits for the mine CEOs and shareholders, they earn a pittance – mere crumbs falling from the tables of rich mine bosses.

Many workers who work for mining companies are employed through contractors who, in essence, serve the same function as labor brokers. This arrangement has created a value chain, wherein mining companies acquire labor power through various recruitment agencies who call themselves contractors – a standard practice for many mining companies. For Implats at least three contractors namely Newrak, Reagetswe, and Triple M serve as conveyor belts, delivering workers for exploitation. The parasitic nature of employment through contractors is clearly visible through the massive pay gap between a Rock Drill Operator (RDO) directly employed by Implats, and an RDO employed through a recruitment agency. RDO’s working for Implats earn a minimum of R17,000 per month with benefits like medical aid and a pension fund, whereas an RDO employed through contractors earns no more than R5,000 per month with no benefits. Crass differences continue to exist despite South Africa’s Employment Equity Act No.55, legislation promulgated in 1998, that declared there must be equal pay for work of equal value.

With Mdazo and his comrades leading the recruitment drive of mineworkers in Rustenburg, it was routine that on at least two Sundays each month, workers received feedback from their leaders and organizers on progress with recruitment and NUMSA getting recognized by Implats. These report back sessions would start at 9am. Thousands of workers would gather at Implats’ Shaft 9 and Shaft 6 to receive an update. Through song, mineworkers would uplift their morale and militant discipline for the battles ahead. Mdazo was crucial in setting up all logistics required for these meetings. Loyal and dedicated to the cause of workers, he would call us on a Saturday evening to make sure we were on course for the following day’s program. Again, he would call in the early hours of Sunday morning to check if we were up on time to deliver reports as the traveling distance between Johannesburg and Rustenburg is about 2 hours’ drive. Working with him, we had to understand workers’ time to be prioritized and respected.

During the report back meetings, Mdazo’s dynamism and versatility in recruitment and organizing was always out in full force. In football, we would call him a utility player, and in cricket, we call him an all-rounder as he rolled up his sleeves in making sure thousands of comrades come together to listen attentively to reports from their organizers. Mdazo would be seen together with workers in NUMSA’s regalia, lifting his knobkerrie high in the sky, and with emotion leading comrades in song. He was unwavering in his belief that NUMSA will one day take over the entire platinum belt. This optimism and fidelity to NUMSA was not accidental or fanatic. It was his belief in the working class, in organizing, in trade unions, and in democracy which led him to this conclusion. To affirm this he led this song in boosting his fellow comrades confidence:

Sifung’isibhozo, iyhoo haa (We are making an oath)

iNUMSA izophatha, iyhoo haa (That NUMSA will takeover)

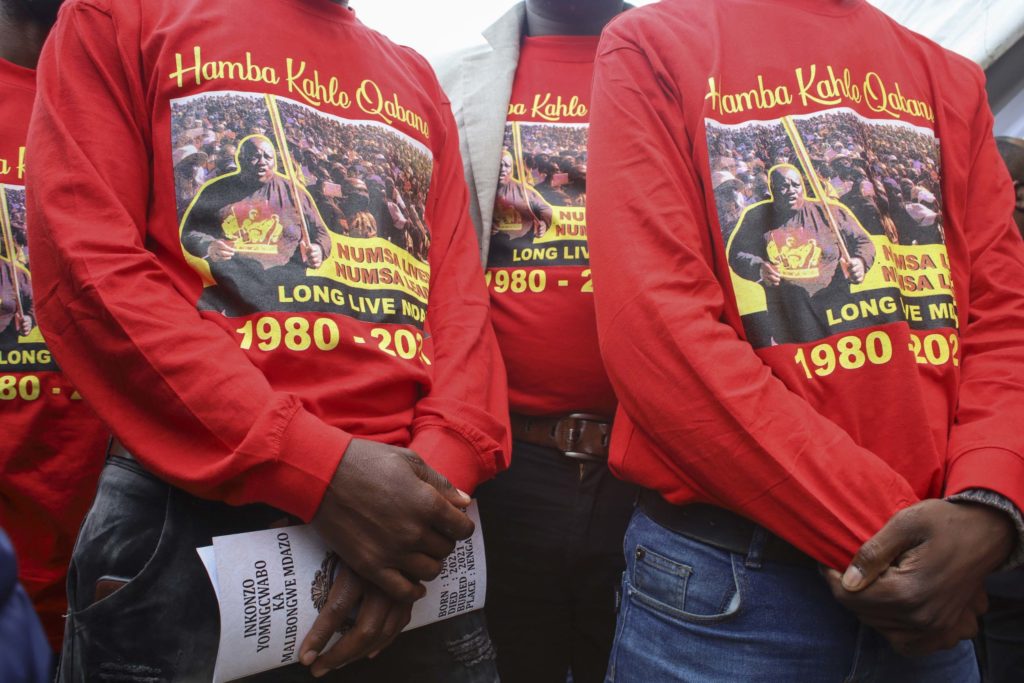

Mdazo was laid to rest on September 4, 2021, at his home in Mqanduli, near Coffee Bay in the Eastern Cape. Acknowledged as a comrade, brother, father, husband, respected member of his community, volunteer, and organizer – Mdazo was humble and respected by everyone around him, from a mineworker to elders in his rural, village community. A large contingent of mineworkers traveled approximately 1000km by bus to ensure a proper sendoff for their comrade and leader. The funeral service itself was reminiscent of the days when Mdazo would organize thousands of mineworkers to gather in the open fields of Rustenburg near railway lines to give report backs. Mineworkers covered in their NUMSA regalia with the words ‘Hamba kahle qabane’ (Farewell comrade) led songs celebrating his life.

The tears of Mdazo’s comrades, family, and community must, like his life, not be in vain. The struggle to transform South Africa’s economy is as relevant today as it was in 1955 when the Freedom Charter articulated mineworkers’ struggle saying, “the mineral wealth beneath the soil, the banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole”.

In NUMSA’s 11th National Congress held in Cape Town recently, NUMSA General Secretary, Irvin Jim, acknowledged Mdazo’s immense contribution to the struggle. In his Secretariat Report, presented to approximately 1000 delegates, he said the following:

“The 11th National Congress must rise and salute sacrifices of many comrades in Rustenburg who took it upon themselves to build NUMSA in the mining industry across the platinum belt. This noble struggle of workers exercising their right to freedom of association led to us a Union losing the life of our courageous, revolutionary volunteer, a cadre and activist of NUMSA, comrade Malibongwe Mdazo.”

In honor of Mdazo’s legacy, we must continue the fight for a South Africa free of oppression and economic exploitation. To remember this giant of NUMSA’s recruitment drive in the platinum belt is to continue the fight for organizational rights and ensuring the yoke and chains of capitalist exploitation in the mining industry become a thing of the past through a decisive class struggle. If we do not take the baton from Mdazo and continue the fight, then many generations of young people from the rural hinterlands of Southern Africa will continue to serve as a bedrock and buffer of the super exploitative mining industry as cheap labor. Mdazo would want us to continue to fight until we destroy capitalism and usher in socialism. He would want us to struggle to ensure that workers share in the wealth of the country.

One year later Mdazo shines as a light and beacon of hope for all metalworkers and workers in general. Indeed, we are the metal that will not bend.

Vuyolwethu Toli is NUMSA’s Regional Education Officer in its Jack Charles Bezuidenhout Region. He is writing in his personal capacity.