In mid-September of this year, Hurricane Fiona hit Puerto Rico as a Category 1 storm. Despite Category 1 being the mildest ranking, the damage was devastating, triggering an island-wide blackout and leaving more than 760,000 without clean water.

After nearly a month since the storm, the reality on the ground is still grim. Officials estimate $172 million in damages to roads, excluding municipal roads, which are the majority. Around 900,000 Puerto Ricans have applied for individual assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). 59%, or three out of every five such applications have been approved. According to Manuel Laboy, the director of the Central Office of Recovery (COR3), FEMA has not approved any of the public assistance applications submitted by the 78 municipalities, 40 agencies and 57 non-profit organizations. FEMA itself has challenged this claim.

“The government still has communities without water and electricity, especially in the central area of the island,” Jocelyn Velázquez told Peoples Dispatch. Velázquez is the spokesperson for Puerto Rican popular movement Jornada Se Acabaron Las Promesas.

“The aid is not arriving as it should,” she added. “The losses, especially in the area of agriculture, have been immense and we have not had the economic conditions for farmers to be able to overcome this process.”

LUMA and the legacy of colonialism

The hurricane has taken 33 lives so far. One of the most recent deaths was of a 75-year-old man who died from injuries related to a fall, which was a result of a lack of lighting in his home. Thousands of families are still without power. Many are arguing that the private US–Canadian corporation which controls Puerto Rico’s electrical grid, LUMA, is at fault.

“It has been 1 month since Hurricane Fiona and 33 people have died in Puerto Rico, according to the Health Dept. Some of those are due to ‘indirect’ causes like lack of electricity,” wrote Puerto Rican journalist Bianca Graulau on Twitter. “In case it hasn’t been said enough before: reliable electricity is a matter of life or death.”

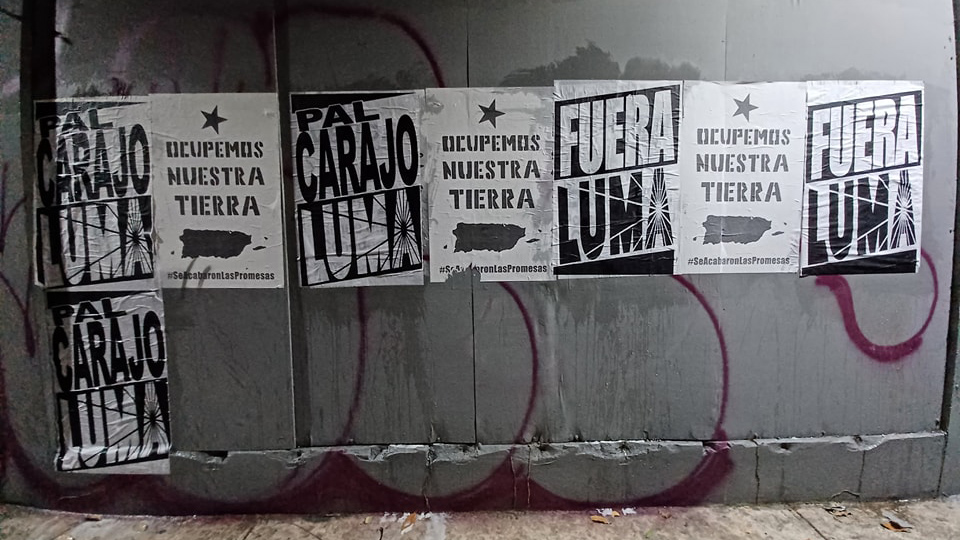

LUMA Energy has been the subject of island-wide protests due to mismanagement of Puerto Rico’s electrical grid. As recently as September, Puerto Ricans took to the streets to demand cancellation of the contract with LUMA.

“We hold the governor, the Financial Oversight Board, the Energy Bureau and the US government accountable for the energy crisis that the island is going through. More than a year ago, it was warned that the LUMA contract would trigger a terrible social, humanitarian and economic crisis. Today, the blackouts and the incapacity of this company are our daily bread,” said Jocelyn Velázquez at the time.

The Puerto Rican government’s contract with LUMA Energy has its roots in another hurricane. Hurricane Maria devastated the island in 2017, killing thousands of Puerto Ricans. But even before Maria hit, Puerto Rico’s public utility company, PREPA, was already bankrupt. After Maria, Puerto Ricans endured an 11-month-long blackout, eroding trust in the system of public utilities. The sheer amount of destruction to public infrastructure also opened up new, cheap investment opportunities for foreign capitalists to privatize public utilities. It is in this context that PREPA signed a contract with LUMA in 2021.

Under the rule of LUMA, power outages have increased alongside electricity prices. Foreign investors continue to be attracted to opportunities in Puerto Rico, especially in tourism and short-term rentals, displacing Puerto Ricans with skyrocketing rent prices, as recently showcased in the short doc/music video by Puerto Rican artist Bad Bunny.

“If there is one thing that this disaster has unveiled, it is first the inability of the colonial government of Puerto Rico to cope with a category one hurricane,” said Velázquez. “The inaction and the criminal negligence of the United States government that imposes its laws on us, imposes its system on us and has become an impediment to the recovery of the country.”

Many Puerto Ricans point to the centuries of colonial rule that the island has endured, as the source of its problems. Indeed, despite many waves of pro-independence social movements, Puerto Rico has been under colonial and neocolonial rule for over 500 years.

Puerto Rico became a US territory in 1917, as it remains to this day. Almost half of people in the rest of the United States do not know that Puerto Ricans are US citizens. However, despite being citizens, Puerto Ricans cannot vote for US president and have no voting representatives in the US Congress. The island has authority over its internal affairs but the US government has control over foreign relations, communications, commerce, the military, and more. In this sense, Puerto Ricans are US citizens, only in the second class.

Puerto Rican authorities began a neoliberal approach to economic matters in the 1970s, which greatly benefited Global North investors who lended money to the island. Over the span of decades, Puerto Rico racked up a debt of $72 billion dollars, leading to a 2014 debt crisis and resulting in the slow collapse of public infrastructure.

In response to the crisis, the US government established a fiscal board to restructure the island’s debt through a 2016 law called PROMESA (Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act). In March of 2022, Puerto Rico exited bankruptcy, but at enormous cost to its people. The fiscal board, known on the island as “La Junta,” slashed public spending for necessary social services such closing a third of public K-12 schools and slashing pensions. To this day, any public spending that the government of Puerto Rico wants to undertake needs the fiscal board’s approval, severely undermining sovereignty.

“We are facing the possibility of possible new hurricanes, new storms, new natural phenomena,” continued Velázquez. “We have neither the infrastructure nor the political and organizational capacity from the state to cope with the possibility of any of these.

“We are still in the struggle. We continue denouncing and looking for a way to make visible worldwide the crime committed in Puerto Rico, and for other voices to join our call so that colonialism in our island is finally ended. And so that we can be a sovereign and independent nation, able to make decisions about our future and to build a different, new and sovereign country.”