On April 25, militant singer, actor, and organizer Harry Belafonte passed away at age 96. The mainstream news cycle has been flooded with tributes to Belafonte, mostly focusing on his musical career. While some have paid tribute to his anti-racist and civil rights activism, there has been an important omission regarding his support to the causes of working people across the globe, even when these struggles were enormously unpopular.

Belafonte was born in Harlem, New York City, the son of working class Jamaican-born parents. He began his artistic career when he was working as a janitor and was given two tickets to see the American Negro Theater. There, he fell in love with acting. In fact, he began his wildly successful music career as a way to pay for his acting classes.

Belafonte won many accolades, including being the first Black person to win an Emmy award and being the first person to to ever sell one million records in a year, a year before Elvis Presley did the same. But Belafonte was far more than just a successful artist. He used his talent and success to bring the music of the Caribbean and US working class to the forefront of pop culture. Belafonte beautifully rendered the struggles of the chain gang through his adaptations of work songs in the album “Swing Dat Hammer,” for which he won a Grammy award. His hit rendition of Jamaican work song “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” is the most successful, and of the song Belafonte said, “Banana Boat wasn’t just a song that delighted people. If they dug deeply enough into the lyrics of that song, the song of great power and protest from the Black voice.” He also popularized the music of singer and anti-apartheid militant Miriam Makeba to US audiences.

Belafonte often cited as his mentor Paul Robeson, a celebrated Harlem Renaissance singer, as well as a communist and a stalwart defender of working class revolutions around the world, especially the Soviet Union. Robeson was heavily persecuted by the US government for his political beliefs. He was denied a US passport and called to testify before the infamous House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). But despite persecution, Robeson never wavered in his commitment to advocating for the working classes of the world.

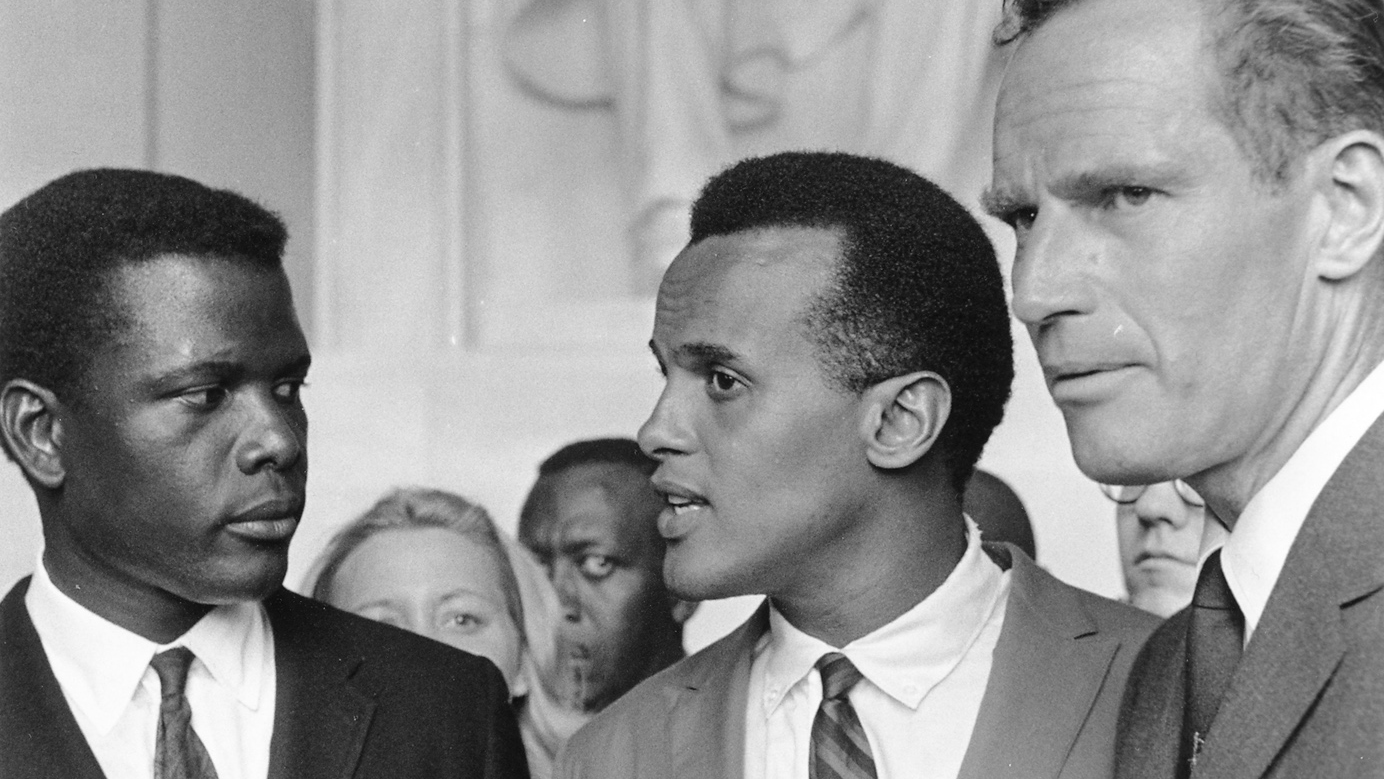

Belafonte followed in Robeson’s footsteps, and supported the causes of working people across the world, even and especially when such support could have risked his career, or even his life. Belafonte lambasted the apartheid government of South Africa and supported Nelson Mandela, even when he was still labeled as a “terrorist” by the US government. Belafonte used his singing fortune to fund the Civil Rights movement, including the Mississippi Freedom Summer Campaign of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). This was no mere passive fundraising. Belafonte risked his life personally transporting cash to SNCC, having to circumvent white-supremacist controlled banks in the South. Belafonte and fellow Black artist Sydney Poitier were chased, shot at, and terrorized by Ku Klux Klan members while the two drove cash through Mississippi.

Belafonte was close personal friends with Martin Luther King, Jr. They met in 1956, and Belafonte claimed to have spoken to King every day while he was alive. Belafonte has said that he believed that all of those conversations were most likely monitored by the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI), which was heavily persecuting King and other Civil Rights activists. It was Belafonte who paid to bail King out of jail in Alabama in 1963, where King penned one of the most famous texts to come out of the Civil Rights Era, “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

Belafonte was put on the infamous Hollywood blacklist for his activism, directly due to his refusal to perform in the US South from 1954 and 1961 in protest of Jim Crow-era systemic racism.

Following the Civil Rights movement, Belafonte continued to be an unwavering defender of revolutionary activism. Belafonte was a supporter of the Cuban and Venezuelan revolutions until his last breath. In 2006 Belafonte led a delegation to Venezuela, including labor leader Dolores Huerta, scholar Cornel West, and actor Donald Glover. In Caracas, Belafonte told Hugo Chavez, “No matter what the greatest tyrant in the world, the greatest terrorist in the world, George W. Bush says, we’re here to tell you: Not hundreds, not thousands, but millions of the American people … support your revolution.”

Belafonte also met Fidel Castro and traveled to Cuba many times in his life, always upholding and supporting the 1959 revolutionary triumph. On July 23, 2020, the Cuban government awarded him the Friendship Medal. Of the award, Cuban Ambassador to the United States Jose Ramon Cabañas said, “This distinction is an acknowledgment of his trajectory of solidarity with Cuba and his respect and admiration for the Cuban revolutionary process.”

On September 27, 2003, Belafonte spoke at the Church of Reconciliation in New York to advocate for the release of five Cuban anti-terrorism fighters, also known as the Cuban Five. He said on that day, “What is happening with our policy against Cuba is not the American style, it is not the true voice of the American people, it is not the true voice of those of us who deeply, deeply believe in the rights of all peoples, and the freedom of all people and in democracy.”

Harry Belafonte's death hurts. He was a man that put his art and life to the service of the loftiest causes, thus making the world a better place. I feel honored by his friendship.

I convey my sincerest condolences to his family and friends. pic.twitter.com/RCefldlQvo

— Bruno Rodríguez P (@BrunoRguezP) April 25, 2023