When I sat down with Eric Huntley on 13 April 2023 it was under the auspice of interviewing him about the new community garden that he has established—along with filmmaker and organizer Sukant Chandan—in the London borough of Ealing, just minutes away from where he and his wife, Jessica Huntley, ran their bookshop and publishing house. However, it was impossible to contain our conversation to just the ‘Jessica Huntley Community Garden’. It would also have been a huge missed opportunity. Eric and Jessica were pioneers of Black literary publishing in twentieth-century Britain, alongside so much more. While running the Walter Rodney Bookshop and Bogle-L’Overture publications, some of the first ever Black-owned enterprises of their type, they were also founder members of the Caribbean Education and Community Workers Association; helped form the Black Parents Movement in 1975; organized the 1981 Black People’s Day of action march; and established the Supplementary School Move in the community. And that is just the list of activities listed in What’s Happening in Black History? III (2015).

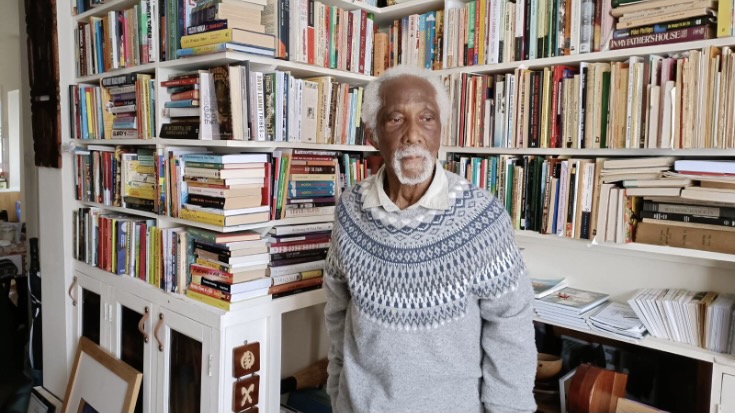

During our wide-reaching conversation, Eric went right back to his earliest political activities in the 1940s of then British-Guiana, all the way through to 2023, where the 93-year-old community organizer and former-publisher is still working tirelessly to bring about radical change in British society.

The Huntley’s legacy in Britain has been well-documented, commendably in Margaret Andrews’ book Doing Nothing Is Not An Option: The Radical Lives of Eric & Jessica Huntley (2014). After arriving in London between 1957-58, they started Bogle-L’Overture Publications in 1968 out of the front room of their house at 141 Coldershaw Road in Ealing. The bookshop followed in 1974. It wasn’t long before neighbors officially complained to the local council that the Huntleys were “lowering the standard of the street by operating a business in a private house”, and thus they were forced to look for a commercial premises. They ended up finding a place just off West Ealing high-street, that would later be named the ‘Walter Rodney Bookshop’ after the Guyanese intellectual who was assassinated in 1980.

Rodney is integral to this story. When I asked Eric what the impetus was for founding the publishers, he first told me the anecdote that often gets repeated: Eric and Jessica were close with their Guyanese compatriot, both ideologically and socially, and when his writing and lectures were banned by the Jamaican government in 1968, the Ealing-based couple decided to publish his collected speeches in the book The Grounding with my Brothers. But then Eric corrects himself. While that was certainly true, his first foray into publishing came in Guyana over a decade earlier.

Guyana was still under the yolk of British colonialism when Eric was living there. He was a member of the anti-colonial People’s Progressive Party (PPP) who ran as a pro-independence group, although Eric is modest about his role: “Jessica and I didn’t have any skills, we were working class people. Most of the people in the leadership of the party were middle-class doctors and lawyers and so on” [1]. In 1951, while working as a postman in the village of Buxton, Eric saved up for a flatbed duplicating machine, “I produced an unofficial journal for the Post Office Workers’ Trade Union using that equipment. We literally starved that month. Three years after, in 1953, the security forces seized the machine on one of their raids looking for contraband literature.”

1953 was a turning point for the Guyanese independence movement. The PPP won a mandate from the public to govern, yet months later the colonial British regime suspended the constitution then conducted a widespread, violent crackdown against the PPP and anti-imperialist groups. As was common all over the world at that time, the British Empire wanted to nullify the upsurge in communist popularity that was permeating amongst the population and specifically cited concerns over the influence of communism as justification for their actions.

Marxist-thought was indeed popular amongst Eric and his comrades. He notes that communist ideas first found their way into the Guyanese zeitgeist through the soldiers who had gone abroad to fight in World War Two then returned home with battered copies of various Marxist texts. Some of these soldiers had been inculcated by members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), with whom Eric had a very short-lived relationship when we first arrived in Britain (he recounts how he and his fellow Caribbean communists had a meeting at CPGB headquarters on Farringdon Road, London, but never returned after they were kicked out mid-discussion at nine in the evening: “we had just from the tropics where we were our own masters”, Eric recounts, “the night was young and when you start talking politics you go into the morning!”).[2]

Communist organizing in Guyana begins to pick up pace after the success of the Cuban Revolution. Eric recalls how delegates from the PPP begin to travel to Cuba and the Soviet Union and bring back “ideas and books” that were disseminated through lectures and study groups. Excluding Andrews’ biography, the foundational role that Marxism plays in Eric’s thought and life is often dismissed in the literature written about the Huntleys, even though he was keeping company with the likes of Marxist scholars C.L.R James and Walter Rodney, and facilitating the International Book Fair of Radical Black & Third World Literature in the 1980s. Eric stresses this point to me: “Our teacher was what was happening on the ground here. We took a Marxist outlook which I haven’t lost and forms the basis of my world view.”

However, he does highlight that Marxism, in particular the Eurocentric variety popular in 1950s Britain, sometimes felt alien to the newly-arrived Caribbean diaspora:

“We came from the colonies with a Marxist perspective, [although] you left home without any consideration for the color of your skin and only you became aware you were Black when you came to England. And therefore the politics, the way you viewed the world, changed completely. We never really read Marxist books when we came here. In the colonies, that was all we had. In England, the racism, the issue of ESN (Educationally Subnormal schools), SUS [laws] became more important.”

In other words, it sometimes felt like the issues facing the Black diaspora in England at that time had “nothing to do with [the] Marxism” that they had been reading about in their homelands. Eric even suggests that making these issues too party political could be a hindrance to change: “There was more political value out of our struggle if we concentrated on [specific] issues […], with SUS it was much easier to come together.” Which is also why Eric and Jessica, in spite of all their organizing efforts, never attempted to form a political party in England. Forming a party meant attempting to reconcile too many differences within the community, and that is without considering the angle of personal belonging too, “we didn’t really see ourselves as residents here, and settled, to form a political party. It didn’t enter our thoughts,” Eric told me.

Bringing together the community was central to the vision of the Huntley’s Walter Rodney Bookshop. Even before it moved to the commercial premises at Chignell Place, the bookshop was a hub for the migrant community of Ealing: “The bookshop became a virtual advice center where persons called for advice on a wide range of issues”, wrote Eric in 2015. People came for “addresses of solicitors in the event of being arrested on being being a person preparing to to commit an offense (SUS), accommodation, social and welfare issues.” Maybe unsurprisingly, Eric also mentioned how they would often host visiting writers, activists, and throw parties. These events brought the Huntleys close to the international anti-imperialist movements of their time, especially the Grenadians.

Bogle-L’Ouverture publications was just one of three Black-owned publishers operating at that time in London, the others being New Beacon Books established 1966 by John La Rose, and Allison & Busby established 1967 by Margaret Busby and her partner Clive Allison. Rather than seeing each other as competitors, they often collaborated with one and other, coalescing on multiple fronts, including organizing the aforementioned International Book Fair of Radical Black & Third World Literature—which ran for over a decade—and founding Bookshop Joint Action, created after a spate of racist attacks on Black and Asian community bookshops in the seventies. The Walter Rodney bookshop itself was defaced on multiple occasions.

Throughout our conversation, I was enthralled by how much the Huntleys had achieved in such a short space of time and with so little financial support. When I expressed this to Eric he was, in what was a common trait of his, fairly self-effacing about it: “Today if you have an idea, the first question they’re going to ask you is…how are you going to manage? Where are you going to get the money from? We never started off like that! Once you had an idea, you went ahead and somehow put it into practice.” In order to publish their first book, they printed posters and greeting cards and sold them to raise the funds; when they first opened the bookshop, friends who worked in offices would liberate stationary from their workplaces and supply it to them.

It has been in this revolutionary, almost punk, spirit that Eric and Sukant Chandan, a collaborator and fellow Ealing resident, have founded the ‘Jessica Huntley Community Garden’, commemorating Jessica who died in 2013. Eric’s environmental work began in 1995 when he started the quarterly magazine Caribbean Environment Watch. But the community garden, in its own way, is closer to to replicating the dynamics of the now-defunct bookshop. The pair hope it will become a gathering place for local people to discuss their issues, as well as find some joy. “It is a fitting legacy [for Jessica]. To put our communities into the center ground, literally, to put them into the center ground in this beautiful way,” Chandan remarked. “In West Ealing, like in many other areas, gentrification is marginalizing people further, so this is about bringing the people at the margins to the center.”

Eric added to this his concern with the effects of the pandemic on people’s social lives, particularly young people. While on a simpler note, he affectionately remembered Jessica’s love of gardening: “Jessica herself loved flowers. When we first came to the country we were unaware of what the flowers and vegetation was like. We kept a lot of the weeds in the garden, once they flowered, to us they were fine, they were flowers. We didn’t realize that as far as the English are concerned they are weeds. So we found ourselves keeping a lot of weeds in the garden.”

There seems to be a lot of hope bound up in the new community garden and hope is a word that begins to reoccur frequently—much to Eric’s own jocular amazement—at the close of our conversation. “You hope at the end of the struggle you can show some progress,” remarks Eric. “A lot of ground work has been taking place across various ages and we’re seeing it coming out now. Look what the The Guardian [has published]. […] This is not a miracle.” Eric here was referring to the The Guardian’s recent investigation into itself called The Cotton Capital, exposing the newspaper’s link to the Atlantic slave trade.

I express some cynicism about both The Guardian’s investigation and the downturn in a coherent revolutionary-left resistance to the problems of contemporary capitalism. Eric is thoughtful and respectful of my youthful impatience: “Sometimes you need a magnifying class […] but the movement is taking place.” He gives the example of today’s young environmental activists, who despite being sons and daughters of the middle-class, have made some extraordinary sacrifices and faced heavy repression for decades. “They came down on them like a ton of bricks,” Eric points out. But now, he suggests, the tide is turning against the big polluters.

Generations sometimes react differently to the same issues, but it doesn’t mean the struggle has disappeared. Chandan reminds us that these days, for better or worse, much of life is taking place online. That said, the community garden itself then becomes a statement, an antidote to the world of online class conflict, seeking to rebuild a different kind of public forum where local people can drop by and discuss existing issues with each other. Who knows what will emerge from these dialogues, but as Eric is always keen to remind us, “doing nothing is not an option”.

[1] In truth, the couple were clearly revered by the PPP leadership. Eric was a member of the party’s general council and a campaign manager in 1953. Jessica was requested to run as candidate for the constituency of New Amsterdam in Guyana’s 1957 general election. While Jessica failed to win her seat, the PPP were again victorious.

[2] Andrews (2014) writes that Jessica and Eric also campaigned for the CPGB candidate for Hornsey, G.J. Jones, in the run-up to the 1959 UK general election.

Rohan Rice is a writer, photographer, and translator from London. You can find his work at: https://rohanrice.substack.com/

First published on Freedom News