From May 29 to June 8, 19 Brazilian Black movement leaders traveled to the US to meet with major international organizations to fight for an end to racist violence. These leaders, all of whom are women or people with diverse gender identities, have over 30 years of experience in Brazilian social movements. The delegates are all part of various groups within the Black Women Alliance to End Violence (Aliança Negra Pelo Fim da Violência), which aims to support “the strengthening of the national and international actions of cis and transgender Black women in their fight to end violence towards Black people.”

Traveling between New York City and Washington DC, the delegates met with US Congressional representatives, academics, activists, and international organizations including the United Nations (UN), the Organization of American States (OAS), and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (ICDH). The movement leaders presented a dossier on violence against Black people in Brazil, and several recommendations on how to stop it.

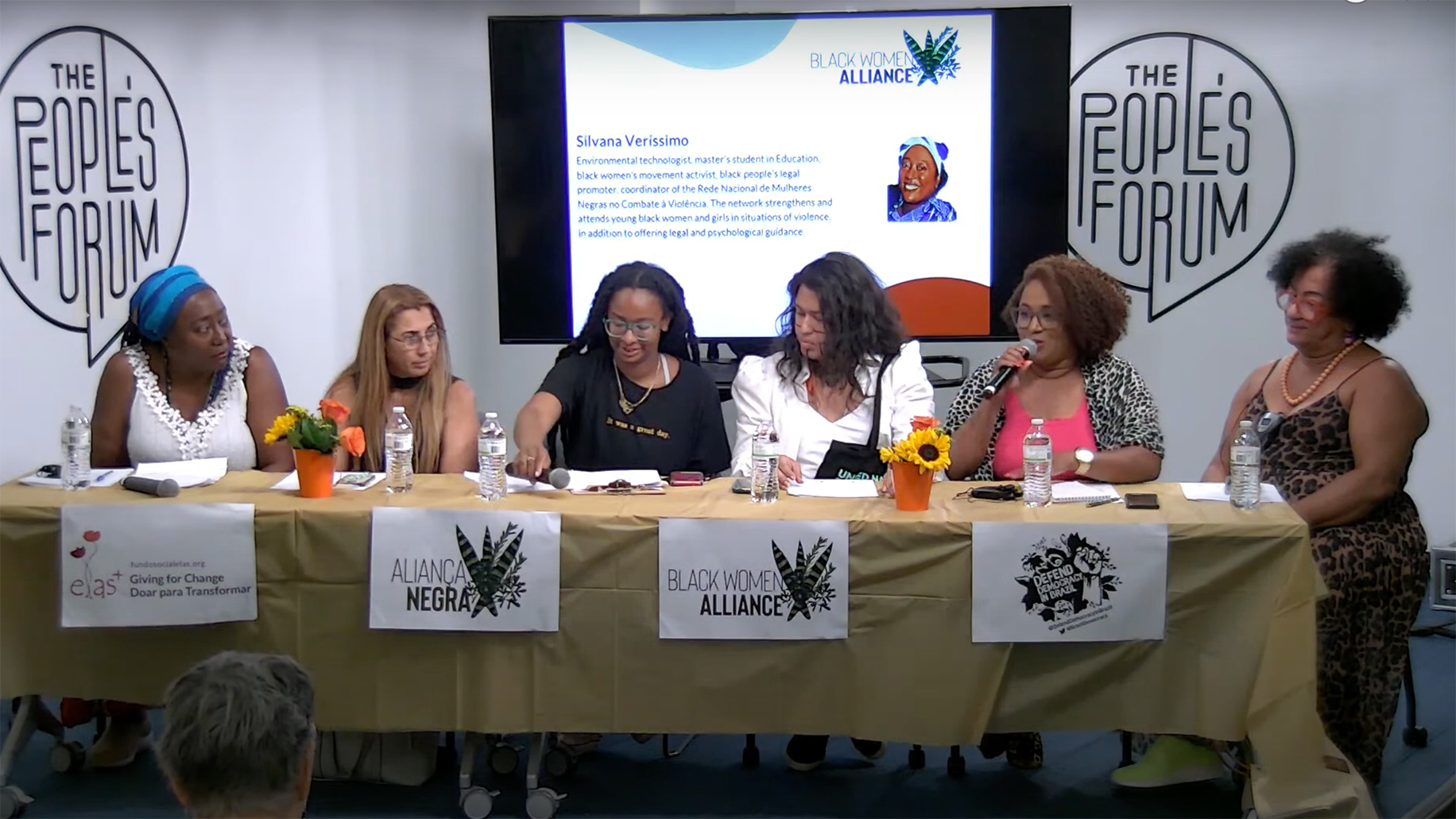

The delegates also spoke at an event hosted at the Peoples Forum in New York City, and organized by Defend Democracy in Brazil and the ELAS+ Fund, where the movement leaders discussed their struggle against racist institutional violence in Brazil. Jovanna Baby, a transgender woman (“travesti” in Brazilian Portuguese) activist who presides over FONATRANS (Forum Nacional de Travestis e Transexuais Negras e Negros), spoke to Peoples Dispatch about the prevalence of violence against Black transgender women, in particular. When Black transgender people are killed, says Baby, “Both society and the data do not present these victims as Black people, they are only trans people. They do not record the racism of these murders.”

According to Aliança Negra’s dossier, “In Brazil, 7 in 10 femicides are of Black women and for the sixth year in a row, trans people—especially Black trans women—are those most likely to be murdered, representing 76% of the deaths registered in 2022, with an increase of 79.8% between 2017 and 2022.”

“And the way [Black trans] people are killed is very cruel,” Jovanna Baby says. “When they kill a trans person, they leave a note or write on their own body that ‘Black people have to be macho,’” Baby says, describing the intersection of racism and transphobia in these crimes.

Peoples Dispatch also spoke to journalist Alane Teixera Reis, of the the Network of Black Women of the Northeast (Rede de Mulheres Negras do Nordeste) and the Articulation of Organizations of Black Brazilian Women (Articulação de Organizações de Mulheres Negras Brasileiras). She believes that there has been a small positive change in the way that violence against Black people is reported in the media, which was largely achieved due to the work of Black social movements. There is a “long history of political organization of the Black population in Brazil,” she says, which goes back more than 350 years. “It starts with the abolitionist uprisings, with what we will call the quilombo [maroon], which is the first political organization, the first idea of free society that we have in Brazil. These were the quilombos, with enslaved Black people who ran away and created these societies.”

But much later, “We consider that the contemporary Black movement in Brazil started around 1940. And since then we have been denouncing the genocide of the Black population with these very terms.”

“Black people in Brazil have been the victims of a historic genocide,” reads Aliança Negra’s dossier. “Practices of extermination have intensified and become more sophisticated over the years. Although Brazil is a country with a majority Black population, institutionalized racism has had an impact on generations, increasing inequality and promoting institutionalized physical and cultural extermination; it is a legacy of slavery[‘s] past that Brazil pretends it has overcome.”

Reis says the murder of George Floyd was a crucial “external factor” influencing the positive change in the media narrative around racial violence in Brazil. According to Reis, when George Floyd was killed and the anti-racist uprisings in Brazil began, mainstream Brazilian journalists were describing racist violence in the US “as if it was something from outside and not something that also had to do with us.”

However, working class Black people stood up against this narrative, says Reis. “The Black people that work on the street washing cars talked about it, the working people, the housekeepers, the people that were at all levels, thought it was funny that the newspapers in Brazil were talking about George Floyd” as if racism was unique to the US. “All the large media organizations started to be embarrassed because they were being denounced by the most standard people,” and then the narrative changed, says Reis.

“The major Brazilian media outlets are racist in their silence regarding racial questions in their production of news,” Aliança Negra writes. “This violence isn’t presented from a racial viewpoint, either through the classification of the torturers or of the victims. Regarding coverage of police actions in the press, of the 7,062 reports that involve policing, the expression ‘Black’ appeared only once. The expressions ‘racism’, ‘race’ and ‘racial’ weren’t mentioned even a single time.”

Aliança Negra recommends several measures to end racial violence in Brazil. For example, the Alliance calls on the Brazilian government to “take responsibility for cases of violence and apply stricter punitive measures against the curtailment of Black population rights, such as the invasion of territories in favelas [slums] and urban outskirts, and police operations without legal foundation.” Brazil must also “confront institutional racism and the genocide of the Black people, with revised plans for public policies for safety and combat [the] newest racist technologies such as the policies regarding facial recognition and racial profiling.”

“Urgent measures should be taken to curb and eradicate police violence in any phase of policing, whether from police, or the armed forces, in the fulfillment of their missions on Brazilian soil,” the Alliance also recommends. Aliança Negra also calls for “the investigation of crimes committed against LGBTI+ people in any territory and [the facilitation of] the collection of public data about these crimes.”