The COVID-19 pandemic continues to reverberate in many aspects of life in Brazil, with nutrition being one of them. A survey conducted by Fiocruz’s Childhood Health Observatory (Observa Infância) analyzed data on overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in the country and in each region. The findings revealed that the pandemic has contributed to an increase in overweight among age groups up to 5 years old and between 10 and 18 years old. However, the problem was already serious before the pandemic, as Brazil surpasses the global and Latin American averages for childhood obesity.

“We tend to blame sedentary lifestyles, the difficulty of reaching or the absence of public spaces due to social distancing and isolation. However, what we observe is that hunger and food insecurity also increased during this period,” says Cristiano Boccolini, a researcher and professor at Fiocruz who coordinated the survey, in an interview with Outra Saúde. But how can the return of hunger impact what seems to be its opposite, weight gain?

Read more: Tackling malnutrition in an era of political uncertainty: the case of Brazil

The answer, according to Boccolini, lies in the increased consumption of ultra-processed foods—industrialized food made up of ingredients of very low nutritional quality, enriched with preservatives, flavorings, sweeteners, and other chemicals. These range from stuffed cookies and frozen lasagna to bread rolls and cream cheese. “Paradoxically as it may be, the situation of food insecurity leads to an increase in the consumption of ultra-processed foods because families are unable to prepare their own food or buy healthy, real food. They end up using ready-made and semi-ready-made foods, which have all these chemicals,” says Boccolini.

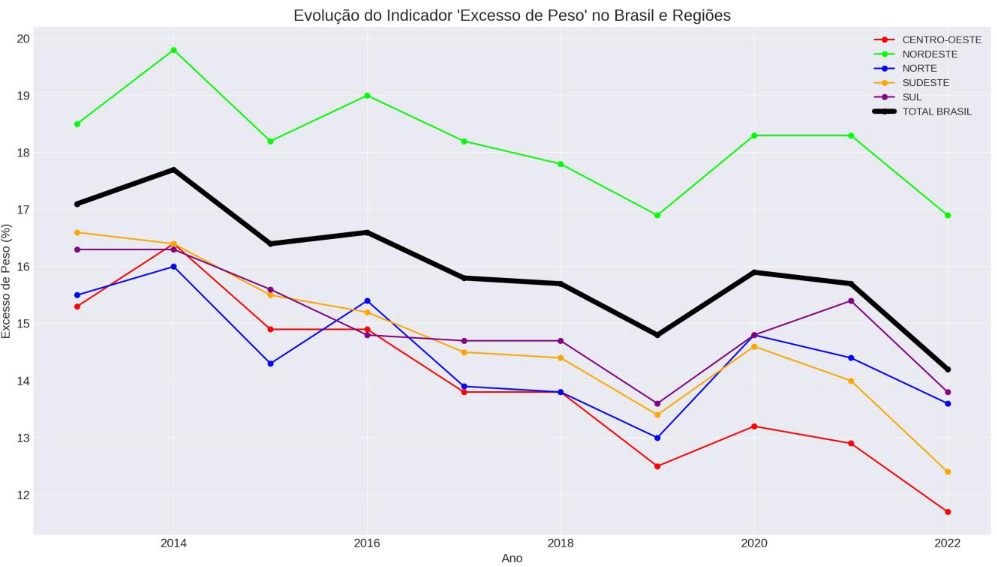

During the pandemic, between 2020 and 2022, food insecurity—in which a person does not have full access to food every day—impacted 70.3 million Brazilians, according to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). As graphs from the Observa Infância’s survey show, the impact on eating among the youngest was significant. Among children, the previous general downward trend in overweight children was clearly reversed in 2020. Observing this age group, up to 5 years old, is relevant because it is a phase in which babies transition from breastfeeding to solid foods. It’s a very important period for their development.

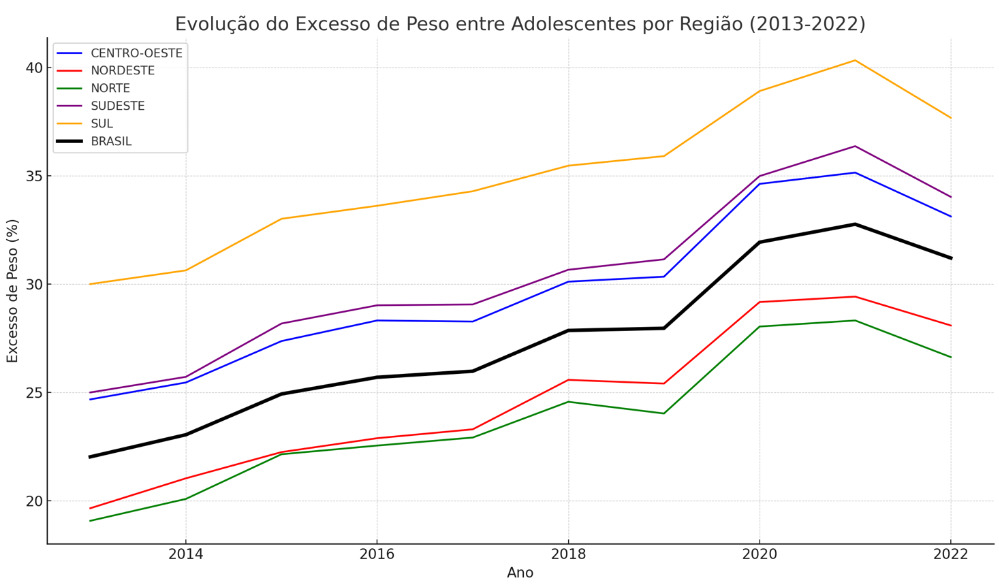

Adolescents between the ages of 10 and 18 who are going through their school years gain relative autonomy in terms of their diet during this period. This age group raises concerns because it shows an opposite trend to younger children: over the last 10 years, there has been an increase in overweight children. This growth was pronounced in the years of the pandemic, followed by a drop in 2022, but still well above the 2019 figures. Last year, almost a third (31.2%) of adolescents were overweight, well above the global average (18.2%).

There is another very clear element in the graphs that makes understanding the phenomenon more complex: the disparity between regions. Boccolini explains that one of the reasons why more overweight adolescents can be found in the South is the greater availability of ultra-processed foods. The fact that the population has higher purchasing power than the average population also contributes to this. This also shows how the profile of consumers of this type of food is vast, and its overwhelming presence affects all social strata.

According to the Observa Infância survey report: “The Northeast stands out with the highest rate of overweight children and, at the same time, shows a more modest downward trend in historical terms. It is noteworthy that, although the Midwest has the lowest percentage of overweight children, it leads in terms of average annual reduction of overweight children. This situation reinforces the case for regionalized measures and interventions, taking into account the particularities of each region.”

Boccolini believes that the recent regulation of labeling of ultra-processed foods, which clearly marks those that are high in sugar, fat, and sodium, is an important measure to start tackling the problem. “We hope that this type of action, as in other countries, will have an impact on the consumption of ultra-processed foods and, consequently, a reduction in obesity,” he says. But we need to go further, he adds, by increasing taxes on these types of products, “including soft drinks, cookies, sweets, and others.”

The researcher also highlights the role that schools and advertising play in shaping eating habits: “There are successful policies to restrict the consumption of ultra-processed foods in the school environment, to ban or restrict sales inside schools. Often these apply to the perimeter of schools because the appeal to consume these foods is very pronounced on social media, through influencers and YouTube channels. There is an appeal, aggressive marketing, often abusive, of these products aimed directly at teenagers. So there also needs to be greater regulation on the promotion and marketing of these products to the teenage public.”

The article was written by Gabriela Leite, and originally published in Portuguese on Outra Saúde.

People’s Health Dispatch is a fortnightly bulletin published by the People’s Health Movement and Peoples Dispatch. For more articles and to subscribe to People’s Health Dispatch, click here.