Loyalty to petrified opinion never yet broke a chain or freed a human soul.

Mark Twain.

- In the flurry of events that led to the NATO war on Libya in 2011, a question was asked of UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon: how do you know that the Libyan government is attacking civilians? His answer, ‘press reports’. When pressed about the nature of these reports, a senior UN official told me that the UN Secretariat had been following closely the reports from al-Arabiya. Al-Arabiya is the official news outlet of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, an active belligerent in the conflict. Later, even Western human rights organizations such as Amnesty International found that the al-Arabiya accounts had been either manufactured or exaggerated.

- As the hot summer of 2016 slipped away in India, 180 million workers went on to the streets for a massive strike against the policy direction of the Indian government. This was the largest strike in recorded history. Only tens of millions of Indian workers are in organized trade unions, while the rest – mostly in the informal sector – are outside the structure of trade union activity. Nonetheless, the trade unions took up issues not for their members alone, but for the entire working-class – especially those in the informal sector. There was virtually no coverage of the strike. Some photographs appeared in the media, but without context, without a news report that explained the demands of the workers.

- Nothing is more bewildering than the way the corporate media spins events in Latin America – supporting coups in Venezuela and Honduras in the name of ‘democracy’. False claims – such as that the president of Honduras Manuel Zelaya wanted to extend his term in 2009 – are legion. Even more common is the easy assumption that left-leaning political leaders are dictatorial – ‘Hugo Chávez wasn’t a dictator, but he crushed democracy’, said the Globe and Mail – while the same papers and television channels go soft on the right-wing leaders in the region. There is little attempt in this corporate media to understand the constraints of these governments, their commitments and their achievements.

These are three instances of a media almost deliberately keen to suppress information about popular initiatives and certainly keen to promote a view of the world that supports the powerful. Sanctimonious dismissal of efforts to make change is commonplace in this media landscape: we are told that entrepreneurs, not workers, make wealth; we are told that imperialist aircraft bomb for democracy, not for power. We are told that up is down and down is up – and, in the absence of serious challenge to this dynamic – we are led to believe what they say.

‘The ruling ideas of the age are the ideas of the ruling class’, wrote Marx and Engels – both with experience as journalists and as political agitators. It is a commonplace view. The class that owns the media controls both the narrative of the media, and therefore, the transmission of news about events through this media. What happens in the world is not experienced transparently, but through media channels. If the dominant classes control these channels, they also control what is known and how it is known. This is the cause of bewilderment and suffocation. It is also the cause of the decadence of culture. When Vineet Jain of the Times of India says, ‘We are not in the newspaper business. We are in the advertising business’, he admits that money is their objective, not cultural development. When ‘fake news’ becomes a term in common use, you know that high-minded ideas of literacy and culture have taken a beating.

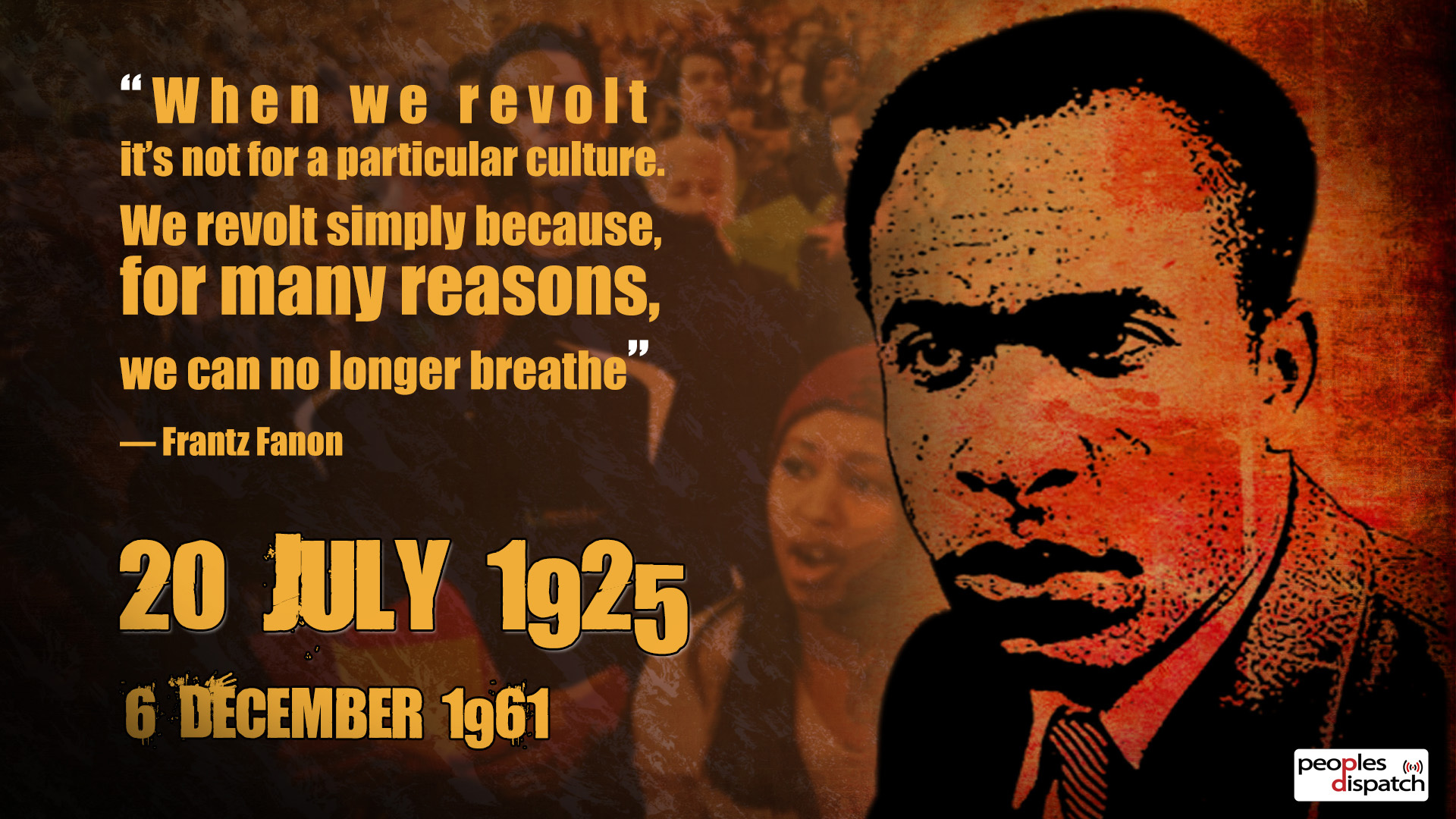

During the fierce conflict in Algeria, when the French armies used their full might against the Algerian patriots, the National Liberation Front (FLN) decided nonetheless to create a media. It had a newspaper and then a radio station. These would be the necessary mechanisms to contest the French imperialist view of things, how the French government pushed its view forward as the universal view of things. Frantz Fanon, who was born in 1925 today, was a key writer in the press and a theorist of the cultural part of the war. In an important essay on the Algerian radio, Fanon wrote of the Algerian who desired more and different news than the French provided. The Algerians, Fanon wrote, want to ‘enter into the vast network of information’. They want to introduce themselves, Fanon jotted down, ‘into a world where things happen, where the event exists, where forces act’.

The point of a media of the people, as Fanon indicated, is not to provide the people with information in a passive way. That is the methodology of the ruling class media – to disarm people, to make them passive, to make them reliant upon the institutions of the ruling class. An integral media, a media of the people, seeks to do three things:

- To satisfy the intellectual needs of the people – to inform people about political events and about the latest developments in science and the arts.

- To elaborate these needs – to encourage people to see how these developments intersect with their own lives and labor, how they could contribute to the growth of a new society.

- To arouse and enlarge the numbers of those who are mobilized not only to consume news, but also – decisively – to make news. The media of the people has to break the wall of discouragement promoted by the media of the ruling class, and to give people confidence to act in the world.

Vijay Prashad is the Director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Chief Editor of LeftWord Books and Chief Correspondent of Globetrotter.