In Colombia, there are currently 1,406 confirmed cases of COVID-19. The government of Iván Duque imposed a strict lockdown that began on March 24, to curb the rapid spread of the virus. However he has yet to implement economic or social measures to protect the country’s vulnerable populations. Street vendors, migrants, and other people who work in the informal sector that are most heavily affected by the lockdown have organized mobilizations in order to demand the government take measures to support them and guarantee their survival.

The incarcerated population in Colombia has also been mobilizing amid the COVID-19 pandemic and demanding that the National Government take measures to protect the population that are forced to live in unsanitary, overcrowded prisons and are not even guaranteed access to water.

Julián Gil, a social leader from Congreso de los Pueblos, is accused of participating in actions of the National Liberation Army (ELN) and has been awaiting trial in the La Picota prison in Bogotá since June 2018. Gil and his organization maintain that he is the victim of political persecution, a legal “false positive,” meant to break the strength of the movement and punish him for fighting for social change.

Gil spoke on the current situation in Colombia’s prisons as a result of the spreading coronavirus crisis and the subsequent recent protests in prisons. These protests took the form of cacerolazos (banging pots and pans), which have been brutally repressed and silenced. Prison guards murdered 23 inmates in the La Modelo prison in Bogotá during one of these protests on March 21. After these events, the authorities are hiding behind the claim of an alleged attempt of mass escape, instead of investigating the events.

What is the current situation in prisons in Colombia and how is the arrival of COVID-19 affecting the incarcerated population?

The accusatory criminal system that we have in Colombia permits incarceration without any evidence, and, as a result, the overcrowding in prisons is at almost 54%. There are prisons in which 5 or 6 people share a cell, sleeping in corridors and in hammocks hanging from the ceiling. These are very complex situations that affect the population which is deprived of their liberty. This population has now reached a total of 123,000 people, when the capacity of the country’s prisons is a maximum of 80,000.

With the announcement of coronavirus and the global pandemic, people deprived of liberty are at high risk, as there are no health facilities nor mechanisms for treatment and care for any type of disease. For example, we regularly get the flu due to the lack of ventilation in this place, which is an ERON-type structure (from its initials, Reculsión Establishment of National Order, which are high-security pavilions). There are not enough doctors or nurses because they do rounds in the different pavilions in the prison, and there aren’t enough of them. There is medication to even treat the flu. There is no medical capacity to deal with a humanitarian emergency of this nature, and as a result, the panic and concern of the prisoners is increasing. Coronavirus adds to the already existing discomfort due to overcrowding and a lack of guarantees of basic rights such as health and a due legal process.

There was a massacre in the Modelo prison in Bogotá during the night of Saturday the 21st of March and the morning of Sunday the 22nd of March. The Colombian Government has claimed that it was an escape attempt, while the Colombian National Prison Movement maintains that it was a disproportionate repression of an organized protest.

Different organizations had called for a cacerolazo that night as a peaceful gesture to attract the attention of society and the State. The cacerolazo was a way of denouncing the humanitarian situation in prisons, given the overcrowding, state abandonment and the indifference of society. This was a protest to attract the attention of local residents, but also of the rest of society. When did it spiral out of control? When the state gave the protest a treatment of war instead of trying to understand the problems that were being denounced. They attacked unarmed people which is a clear violation of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights.

The same happened in the prison in Cúcuta, where a few days later the INPEC (National Penitentiary and Prison Institute) shot at (that we know of) two people. The Justice Minister came out and talked to the media, saying there was a planned escape, but this statement just does not hold up, because there is no possibility of planning an escape in unison across the country’s multiple prisons.

In the light of this pandemic that is coming towards those of us who live in prison, the humanitarian crisis must be resolved urgently.

What is the risk of similar outbreaks happening during this sanitary crisis and new massacres occurring?

What is at stake now is a life plan. People who are deprived of freedom want to live, not escape. We want our lives to be respected.

In addition to the murders, the authorities transferred the people who they assume coordinated this cacerolazo and the “mass escape”. About 25 people from my prison and about 10 women in the Buen Pastor were transferred to the Picaleña prison, which is a punitive prison.

After the repression, the authorities declared a prison emergency, which was one of our requests, but this measure does not seek to address the humanitarian emergency in which we find ourselves. The continuity of expressions of anger and frustration of this type is inevitable, and they will continue because inside there is risk of massive contagion due to the general unhealthiness and lack of medical attention.

Going back to your case. You are by no means the only political prisoner belonging to social movements. Is the arrest of social leaders commonplace?

In the country, we face judicial set-ups. In Congreso de los Pueblos there are more than 62 people subjected to legal proceedings. There are three accused companions with me at La Picota. We call ourselves “false positives” in court because of the similarities with the false positive cases. The “false positive cases” refer to young people who were murdered across the country by the Army, who then present them as guerrilla fighters killed in combat; in our case, it is in response to the demand for results from the Prosecutor’s Office. We believe this to be a strategy to intimidate the social movement, to attack popular proposals and to silence the voices of people who are dissatisfied.

Why is being a social leader considered a crime in Colombia?

In Colombia it is a crime to be a human rights defender, teacher, unionist or social leader. And it has a reason for being this way: we have been governed for decades by a paramilitary large-landowner logic. This logic has diminished the rights of everyone in the country. Today, social leaders represent the defense of communities in their regions and neighborhoods and that poses a serious risk to the interests of monopolies, multinationals and those who currently govern.

At the time of your arrest, what role did you play in the Congreso de los Pueblos (CdP)?

In the last 2 years (2016-2018) I worked as the technical secretary and supported the international commission, political education and finances. Since I can remember, I have been involved in social processes. I was in the seminary of the Claretian missionaries in Boyacá, Casanare, Cundinamarca and Bogotá, where I learned a great deal about grassroots and popular work. Later I participated in the Claretian Corporation Norman Pérez Bello, which is very committed to the issue of human rights.

My work has always been on the side of important causes and populations that have been marginalized, forgotten and have been victims of violence. As a graduate in philosophy, my vocation has been service and education, contributing from the hands that learn, the eyes that see, the ears that listen, from humanity that accompanies me as part of the CdP and as a committed Christian.

What has the support for these types of prisoners been like inside and outside Colombia?

Within the country the support has been very positive. As I said previously, I have always participated in grassroots spaces and for this reason I have been supported by a good number of comrades from rural areas and peasant organizations, as well as teachers.

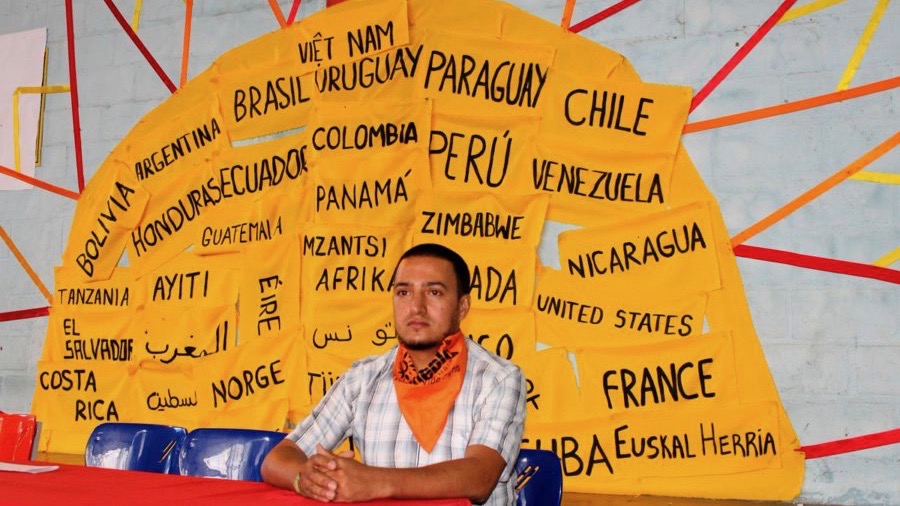

Internationally, I have received support from organizations and social movements in Latin America, Europe and the United States thanks to the fact that I actively participated in spaces such as the Social Movements towards ALBA and Youth in Struggle, who now share and raise the voice of those of us who are prisoners of a government that seeks to silence us.

In Europe, Colombia is thought of as a democracy. Would such actions be acceptable in a democracy?

Colombia’s projected image has always been appropriate for investment opportunities for multinationals. We have lived a process of permanent pacification in which the people have been subjected to the State´s interests. This means a devastation of the territories, where the people who own a piece of land have been dispossessed for the benefit of multinationals to build hydroelectric plants and destructive projects to extract gold, oil, coal, coltan, etc.

In Colombia there is no real democracy, there is no respect for the constitution, and there is a fascist government that shirks its social commitments. Our struggles defend basic and fundamental rights, international agreements of coexistence and respect for life. We must remember that many people have given their lives for their ideas, defending freedom of expression and thought. The government must constantly be told to respect our lives because they are constantly murdering us, massacring our people, the people who have been impoverished by the system.

These cases remind us of similar cases of political prisoners in other countries. To what extent are these judicial processes used to criminalize popular movements?

They seek to break the social movement and spread fear throughout the organized people, the students, the mothers who suffer so much in silence. These arrests seek to enforce this reign of injustice, a government fit for the economy and private interests.

We have been defending my innocence for two years from prison, there is no evidence to prove the accusation. And just like in my case, many people face prosecutions and harsh sentences for having thought and dreamed of a different country. For many years they have wanted to end the social movement and diverse organizational structures.

Are there initiatives, petitions or letters of collective liberation for political prisoners at this time?

The CdP issued a statement in which they requested the release of the prisoners of Casanare, Arauca, as well as of myself. No prison in Colombia has the capacity to deal with coronavirus and if we are left here in prison we are facing the death penalty. Furthermore, the repression has increased because the guards and the police are desperate and violently repress any expression or demand that we make.

What has changed about you since you are in prison?

I got older (laughing). I have been able to hear many stories first-hand, from people who have participated in the armed conflict and their arguments and reasons for doing so, as well as from boys who are here for stealing a cell phone or shoplifting in order to eat. My way of seeing the world has changed quite a bit. Prison serves to distance us from our family and the beings we love. As a cellmate I had at one time said, prison is a space that ends up being a filter through which sometimes only small beams of light pass, which are family, friends, those who have decided to stay with us and support us. Prison is useless, it is a nefarious invention of humanity; it does not go beyond punishment and suffering. People don’t change for the better in prison. Definitely, all of us who dream of a different world and humanity must work towards abolishing prisons. It is not a place where you learn to be humane or democratic. It is a space where the walls, the isolation, the punishments, the handcuffs, the pepper spray, all dehumanize people; And that is our fight: a fight against dehumanization and to maintain humanity against that macabre plan to eliminate us as human beings.

How does jail affect your health? How do you feel on a physical and psychological level?

One physically deteriorates little by little because the food is very bad, it arrives raw, undercooked in the patios, and it does not meet our minimum needs in terms of protein, cereals, vitamins, fruit… Needless to say, I imagine that it is similar or worse in other parts of the world, but here we physically weaken in that sense. Psychologically I stay strong because I have the support of my mother, my nephews, and many comrades like my brothers and sisters in the Quinoa popular process. This love helps me not lose heart.

Would you change any of the things you did before entering prison?

I always devoted a lot of time to popular processes and therefore was regularly absent from family gatherings. I would change that. If we survive this coronavirus, this repression, I will dedicate more time to my nephews and nieces, my family and my mother.

What is the relationship between political and social prisoners like? Are there any common initiatives or changes in their common environment?

It is important to point out that there are no longer separate courtyards for political prisoners, social prisoners and paramilitaries. At the moment we share coexistence yards. Political prisoners of the ELN, the FARC or the social movement, like me, seek the best way to organize ourselves, starting with respecting each other’s spaces and promoting communication. With social prisoners, spaces for joint construction and dialogue have been established. With the Committee of Political Prisoners (CPP) we have built a space for training in human rights to defend ourselves. With the People’s Legal Team (EJP- Equipo Jurídico Pueblos), and some professors from the Pedagogical University and the Pasos Foundation, organizations that defend human rights, we built an educational program that is attended by more than 60 people.

These moments of educating and sharing, listening to the other’s word, perceiving their feelings, their depth in the reflections that are made, have allowed us to channel proposals outside the prison to help dignify and respect prisoners. We also work with the National Prison Movement, an organization that prisoners decided to build 20 years ago and which was somewhat abandoned during the peace process with the FARC. Now, with the worsening of repression, this organizational tool has been taken up again and we humbly participate there as good listeners and interpreters of the situation to make proposals.

To conclude, what procedural situation is your case in? What is the objective of the Prosecutor’s Office?

We are in the trial stage after the preparatory hearings. The next hearing is on April 24 and we hope to continue, that the prosecutor has not suddenly got coronavirus and we can continue to defend the truth with dignity, the right to organize and be critical of what is happening in the country and in the world.

What do you want to say to those who follow your case?

I would like to thank them and tell them that here, there is not, as it’s been said, an escape plan. Here what we have is a life plan, where people have shouted “We want to live” with the door and with the pan in hand.

I am grateful for your solidarity with my cause, which is the cause of billions of people around the world, the cause of justice, humanity and truth. A few words I wish to share with you are that we must always continue forward, defending joy and hope.