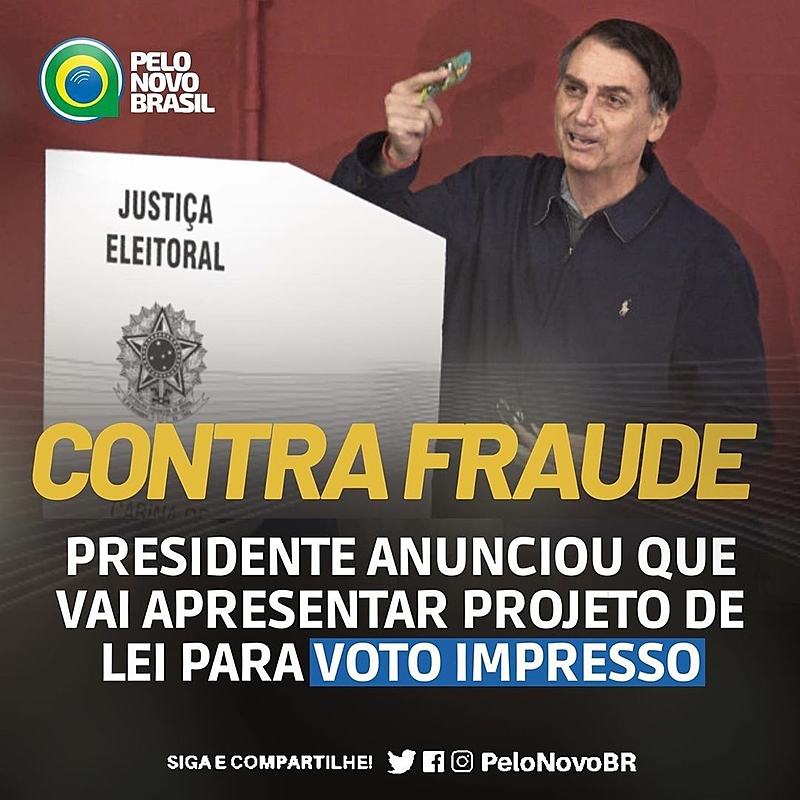

If in the electoral year of 2018, the fake-news which circulated the most on social media platforms were related to the candidates themselves, the current misinformation questions the electoral process itself, according to the specialists interviewed by Brasil de Fato. The recent and constant mudslinging by the president and his allies about the alleged unreliability of electronic voting machines illustrates this.

It’s no coincidence that this agenda is also prevalent in the far-right groups of the deeper layers of Telegram. In these more underground platforms, the far-right has complete dominance. “And the most shared [content], the topics and narratives that have the most prominence in the groups that we analyze are not those directly connected with the allegation of frauds in the electronic voting machines, but with those that question the legitimacy of the institutions that guarantee the result of the election,” says Letícia Cesarino, professor and researcher in the Anthropology Department and in the Program in Social Anthropology (PPGAS) of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC).

In his latest statement, Bolsonaro affirmed that the Liberal Party, of which he is a part, will hire a private company to audit the elections. “The company will ask the TSE [the Supreme Electoral Court] for some information. What could happen? This company, that does such auditing all over the world, can reach the conclusion that, with what they have access to, it was impossible to audit. Look at how far this could go,” Bolsonaro said.

“It has always been there, but this year this issue garnered strength,” says Leticia Cesarino. “On September 7th, for example, an issue that gained prominence was the vaccine passport, but in a kind of crossover with the fraud at the voting machines. There were rumors that unvaccinated people would be unable to vote. So even if it was not their issue [at that moment], the topic has always circulated, at least since September. ”

Bolsonaro’s moves are similar to those made by the former president of the United States, Donald Trump. Even before losing last year’s election to Joe Biden, the businessman had already pointed to supposed election fraud. “Anyway, nothing matters because the polls in California are totally manipulated,” Trump affirmed back then. Even after his defeat, he did not recognize the election results, provoking his electoral base to storm the Capitol building on January 6.

Revealing truths

According to Cesarino, one of the characteristics of these far-right groups that inhabit the underground of social media is positioning themselves as revealing truths that their opponents want hidden. “The way they present themselves as content creators has to do with the idea of them being the ones to reveal the reality the media hides. And that’s how they conquer the faith and loyalty of their followers,” Cesarino says.

Revealing hidden truths is also what president Jair Bolsonaro purports to do. In July of last year, for instance, he promised to show evidence that fraud had occurred in the voting system during the 2018 election. According to him, he actually had won the election in the first round rather than the second, against the PT [Workers Party] candidate, Fernando Haddad. Soon, however, it was proven that the so-called revealed truth was nothing but false allegations that the electronic voting machines were automatically voting for the Workers Party (PT).

“The way [these far-right groups] present themselves as pseudojournalists, has to do with their claim that they are the ones to reveal the reality the media hides. That’s their brand. It makes no sense for them to change their brand, because that’s how they attract consumers and gain their loyalty, with this claim that ‘after the internet the media will never be able to hide anything again,’” affirms Cesarino. “It’s a right wing niche, and it will continue to be, because that’s what works.”

The left-wing, on the other hand, “has a connection with the mainstream media that this right wing, from Congress Man down, don’t have. They have nowhere else to achieve such visibility other than on the internet. So for as much as the left-wing grows, this remains [the far-rights’] niche.”

Organic and artificial flow

These far-right groups also take advantage of people’s insecurities. “The concept of the threat is also very important, because it keeps people connected, alongside to the question of the revelations. The right-wing has achieved its organic network through this normal appeal,” says Cesarino.

Flávia Lefèvre, lawyer and member of Intervozes and the Coalizão Direitos na Rede [Network Rights Coalition], agrees: “the first thing to do is to identify fears and insecurities”, such as the fear of losing one’s jobs, of violence and the suppression of individual liberty.

“Political marketing companies use social media users’ data to identify and form voters profiles, profiling people. And then they define certain messages and fake news to disseminate to these profiles, according to the identified fears and insecurities,” explains Lefèvre.

A good example of this is the fake news directed towards the people of the United Kingdom for the pro-Brexit campaign in 2020. Back then, one of the most well-known lies was that immigrants would steal English people’s jobs. Brazil is another example: “During the 2018 election, these producers and spreaders of fake news started spreading the news that if [Fernando] Haddad won, he would release all prisoners. Then people got scared to death,” described Lefèvre.

With the artificial manipulation of emotion, these groups can attract and trick people into believing in what they say, creating an organic flow of the circulation of misinformation.

Telegram and Youtube

Leticia Cesarino explains that the production and dissemination of far-right content is directly connected to the structural connection between Telegram and Youtube. Until 2018, WhatsApp was the main repository of the content that was produced on Youtube by the far-right. With Telegram, the circulation of these materials reached record numbers. That is because Telegram allows, for example, groups with up to 200,000 people. On WhatsApp, the maximum is 256. Message forwarding is also restricted on the Meta Group platform, but does not exist on the Russian app.

With this, the connection between YouTube and Telegram has become fundamental to the far-right dissemination of misinformation. “YouTube links are widely spread through Telegram. YouTube presumes that it has a control over the platform that it does not have, because it is connected with all the others. Bolsonarism takes advantage of this,” says Letícia Cesarino.

“We observe an incidence of YouTube within Telegram five to six times higher than the second platform, which is Telegram itself,” says Cesarino. In other words, the content that circulates the most within Telegram are Youtube links. In second place are links created on Telegram, which allows live broadcasts. “There is, indeed, a structural relation between these two,” remarks Cesarino.

Despite the fact that Telegram has gained prominence in this sphere, WhatsApp is still more popular. According to the National Telecommunications Agency (Anatel), about 100 million telephone plans are prepaid. This means that people have a limited amount of data, meaning they have a limited access to internet and apps. After their data plan is over, the user has access only to WhatsApp and Facebook.

“In these cases, the user receives news and has no way to check it, because he cannot access other websites and sources. That is why, in 2018, the strategy used for the misinformation campaign was to purchase prepaid chips, in that way one did not need to identify itself at the time of purchase and could spread fake news through WhatsApp in an unlimited way,” explains Lefèvre.

According to the Regional Center for Studies on the Development of the Information Society (Cetic.br), which is a department of the Brazilian Network Information Center (NIC.br), linked to the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee (CGI.br), 95% of the D and E classes only access internet through the mobile network and primarily with prepaid plans. In Class C, the percentage drops to 65%.

“So there are at least 120 million users with limited access to the internet, and that are more vulnerable to these misinformation campaigns than those who can afford an unlimited data plan,” says Lefèvre.

Other apps

While WhatsApp remains important, “the ecosystem as a whole has diversified” according to Cesarino. “We have, for instance, TikTok, which despite not being so large, has an investment from Bolsonaro’s supporters network. However, this is usually under-cover content that lies in that gray area between entertainment and political propaganda. But TikTok videos also circulate on WhatsApp, so there is this flow as well,” affirms the professor.

A study by the media monitoring group Media Matters for America, released in March of last year, showed that TikTok was directing users to far-right content in the United States. More recently, the group reported that the platform’s algorithms are allowing the dissemination of misinformation amid the Russian invasion of Ukrainian territory.

Cesarino adds, “Instagram itself, which does not have much of this political use, has an incidence adjacent to Bolsonaro supporters, with misinformation about early treatment, alternative Sciences, the anti-vaccine agenda.”

Over the years, other platforms have emerged as alternatives to the more traditional ones, especially after mainstream social media platforms began to moderate more, such as banning channels. Far right groups have migrated to platforms such as Gettr, created by members of the former US President Donald Trump’s office, Rumble and BitChute.

Jair Bolsonaro and people such as Bolsonaro’s sons Flavio Bolsonaro (Patriota-RJ) and Eduardo Bolsonaro (PSL-SP), and supporters such as Carla Zambelli (PSL-SP), Paulo Eduardo Martins (PSC-PR), the Brazilian Minister of Communications Fabio Faria and the blogger Allan dos Santos created profiles on Gettr days after it was released. Flavio Bolsonaro described Gettr as “alternative social media in defense of freedom” when announcing his profile to his Twitter followers.

Crossing lines

In Cesarino’s view, it is possible to “greatly increase” the reach of the left-wing on social media, but achieving the level of online influence of the far-right groups is “difficult without crossing certain ethical, and even legal lines.” “They will always be ahead, because they have no limit to their distortion and sensationalism, because [social media] is based on effectiveness, engagement. If media goes viral, then the content will follow the same logic, and what tends to go viral is sensationalism. This is the difference between this type of media and the mainstream media,” she affirms.

“The left-wing is improving its presence, but it is a matter being organic. The Left wing organizations need organic channels. There is no point in PT [Workers Party] having a great communication strategy to speak the language of the internet if there’s no network of organic content creators,” she points out.

Flávia Lefèvre sees another line separating the left-wing groups from this reach: the international funding and support of the production and dissemination of fake news that these Brazilian far-right groups have.

“The industry is very well funded. Here in Brazil, the research that has been done based on the 2018 elections, and that has been done since have revealed that these groups are financed by right-wing forces, not only from within the country, but also internationally. There are international institutions that fund these groups which are focused on the defense of neoliberalism, and the demand to support neoliberalism does not exist only in Brazil,” says Lefèvre.

Brazil, a step backwards

Since 2018, however, Brazil has made little progress in identifying the sectors and groups which finance the production and dissemination of misinformation in the country, according to Lefèvre.

Recently, the Supreme Electoral Court (TSE) enhanced its measures to fight fake news, considering this year’s presidential elections, with the expansion of the Cyber Security Commission to include the incidence of fake news. Now, the Commission will also “monitor elaborate studies and implement actions to fight the mass dissemination of fake news on social media.”

Previously, the TSE and Twitter, for example, signed a memorandum of understanding to join the efforts to fight misinformation in this year’s election process. Among the measures in the memo, Twitter committed to create a tool on its platform that allows users to seek information about the elections without leaving the platform.

These changes, however, are still insufficient to address the spread of misinformation, and are far from identifying the groups funding misinformation in Brazil. “We still don’t know these groups. We need the institutions, the Federal Police, the TSE and the Electoral Public Prosecutor’s office to follow the trail of money and identify the forces that are financing [misinformation],” says Lefèvre. “To confront these ultra-neoliberal right-wing forces, it is necessary to have a very well-articulated network between institutions, parties, civil society and the third sector.”

Between the first and second rounds of the 2018 elections, the then president of the TSE, Rosa Weber, stated that ”fake news is not news“, against which there is no miracle, and that those who have ”a solution to stop fake news” should present it.

This article was written by Caroline Oliveira and was originally published on Brasil de Fato.