Lee en español aquí

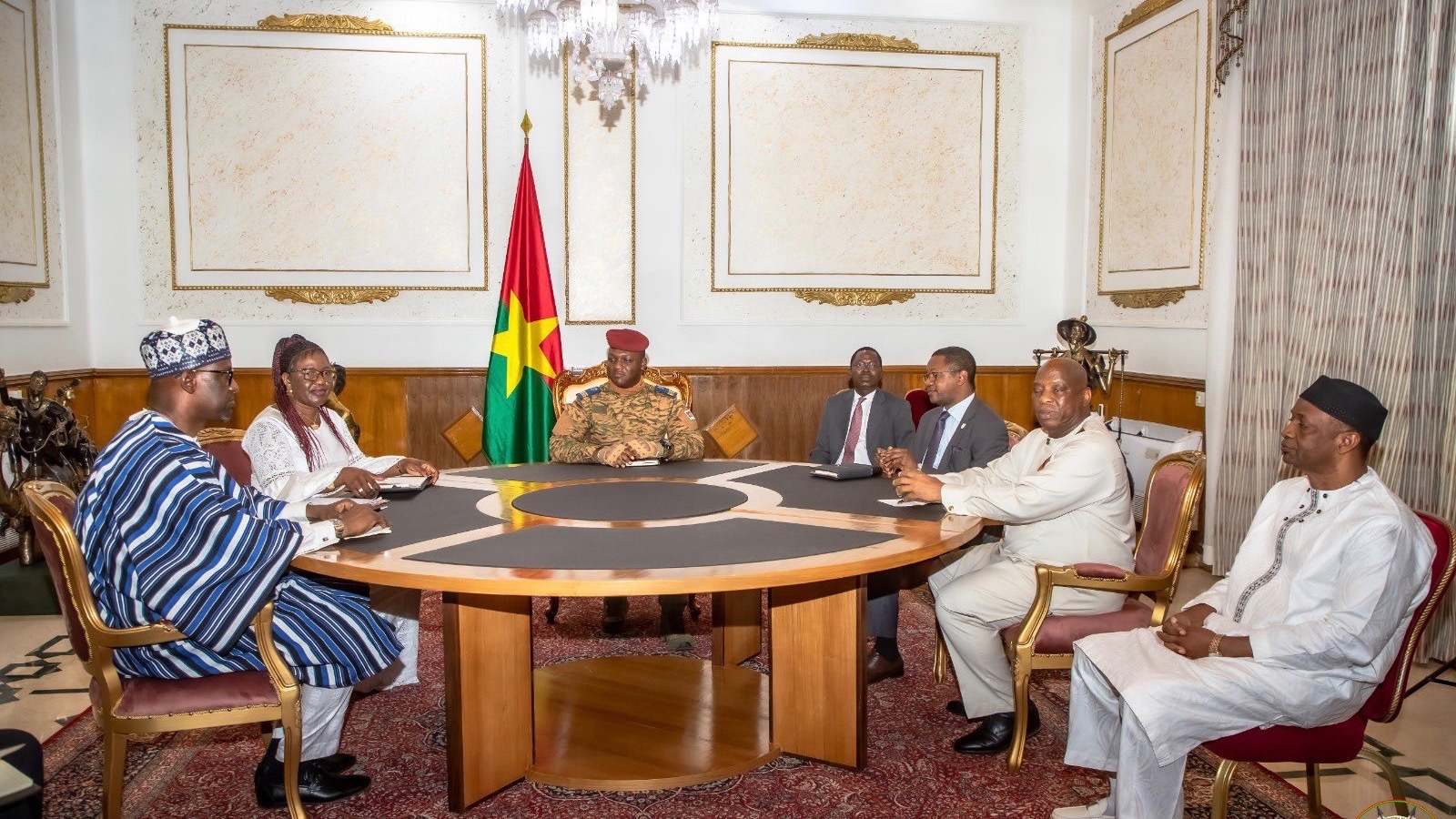

As France is getting ready to withdraw its troops from Burkina Faso by the end of the month, signs of a possible realignment in the region are emerging with a tripartite meeting between the foreign ministers of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Guinea—Olivia Ragnaghnewendé, Morissanda Kouyate, and Abdoulaye Diop—held in Burkina Faso’s capital Ouagadougou on February 8 and 9.

The leaders discussed a range of issues, “in particular the success of the transition processes leading to a return to a peaceful and secure constitutional order,” and, importantly, the “revitalization of the Bamako-Conakry-Ouagadougou axis” to make it a “strategic and priority area” on matters including trade and economic exchanges, mining, transport, roads and railway links, and the “fight against insecurity.”

The meeting was held in the wake of major developments that have taken place in the West African countries over the past two years. In August 2020, the current head of Mali’s transition council, Colonel Assimi Goita, led a coup that led to the ouster of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta. Goita led a second coup in May 2021, deposing transitional President Bah Ndaw, following which he took power as interim president.

Keïta’s removal came at a time of popular unrest in Mali, as anger grew over allegations of corruption in the government and its failure to address growing insecurity in the country. Importantly, protestors demanded the withdrawal of French troops, who had been present in Mali since 2013 to fight jihadist insurgencies, a mission which was increasingly being seen as a failure by the Malian people.

After seizing power, the military junta secured significant victories against armed separatist and Islamist groups. Crucially, in February 2022, Mali’s military-led government formally asked France “to withdraw, without delay, the Forces—Barkhane and the Task Force Takuba members from the national territory,” prompting celebrations in capital Bamako.

These developments were also unfolding in the context of Mali’s isolation from regional economic and political blocs—particularly the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the African Union (AU), both of which had suspended Bamako in 2021. ECOWAS proceeded to impose sanctions on Mali, which were expanded into collective punitive measures including border closures, the cutting off of financial aid, and a trade embargo on the land-locked country in January 2022, sparking massive protests.

The move was also condemned by civil society organizations, given that Mali was importing 70% of its food requirements and nearly one-third of its population is dependent on humanitarian aid. The sanctions were partially lifted last year after Mali’s interim government presented a transition plan with legislative elections scheduled for late 2023, followed by presidential elections in February 2024.

Meanwhile, just months after the coup in Mali, armed forces led by Colonel Mamadi Doumbouya in Guinea led a coup against President Alpha Conde in September 2021. Conde was removed from power in similar circumstances of public discontent against the government, including accusations of corruption.

Guinea was also subsequently suspended from ECOWAS, and had financial and travel-related sanctions placed on its new military rulers. The US government, which had publicly supported the sanctions, proceeded to remove Mali and Guinea as beneficiaries under its African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) trade pact.

Additional ECOWAS sanctions were enforced in September 2022, with the bloc’s Development Bank also announcing that it would suspend financing for development projects in Guinea.

At the time, Mali’s then interim Prime Minister, Lieutenant Colonel Abdoulaye Maïga, announced that the transitional government had “decided to break away from all illegal, inhumane, and illegitimate sanctions imposed on [Guinea] and will take no action on them.” Guinea and Mali also proceeded to sign multiple cooperation agreements in November 2022.

2022 also saw two military coups in Burkina Faso—the first in January when a group within the army called ‘Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration’ (MPSR), led by Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Damiba, ousted President Roch Kabore.

While Damiba had been entrusted with the task of recovering one-third of Burkina Faso’s territory that had been lost to armed groups, his failure to do so led to a second coup in October, led by 34-year-old Ibrahim Traore. Burkina Faso was suspended from ECOWAS in January 2022. The regional bloc and the military leadership subsequently reached an agreement for a two-year transition with elections in 2024. The country was also suspended from AGOA in January 2023.

The communique issued following last week’s tripartite meeting condemned the “mechanical imposition of sanctions which often fail to take into account the deep and complex causes of political change,” adding that these measures “affected populations already battered by insecurity and political instability,” “undermine sub-regional and African solidarity,” and “deprive ECOWAS and the AU of the contribution of the three countries needed to meet their major challenges.”

While calling for “technical, financial, concrete, and consistent support” for security efforts and the return to a normal constitutional order, the three countries have agreed to “pool their efforts and undertake joint initiatives for the lifting of the suspension measures and other restrictions.”

Just days prior to the tripartite meeting, Burkina Faso’s interim Prime Minister Apollinaire Kyélem de Tambela visited Mali, proposing the formation of a “flexible federation” between the two countries, recalling the first federation that had been formed between newly-independent Mali, Senegal, Benin, and Burkina Faso in 1959-60.

During the visit, Mali’s interim Prime Minister Choguel Kokalla Maiga reiterated the principles that the Malian junta had adopted: the defense of its sovereignty and the freedom to choose its foreign partners and national interests.

After ordering the removal of French troops, Mali has since sought military assistance from other countries, including Russia. In January, Burkina Faso announced that it had terminated a security agreement with France, adding that it had given the country one month to withdraw the 400 troops deployed in the country as part of Operation Sabre.

With the deadline drawing close, it has not been confirmed if France will recall its troops entirely, or whether they will be redeployed elsewhere. In the case of Mali, for instance, France had stated that its troops would be stationed inside the border of neighboring Niger, which would serve as the new base for its military presence in the Sahel, a move rejected by civil society groups and activists in the country. An estimated 3,000 French troops are still present in the Sahel, particularly in Niger and Chad.

It is also important to note that France is by no means the only imperialist power operating in Africa. The US, specifically through the US Africa Command (AFRICOM), already has 46 bases on the continent, and some form of military relations in 53 out of 54 African countries. It is now undertaking a concerted effort to expand its influence, particularly as it seeks to counter Russia and China’s ties with various governments.

Meanwhile, in the midst of all these contests, progressive forces in West Africa are striving to articulate their own agenda of sovereignty, of Pan-African unity, and of the fight against imperialism in all its forms—be it military or through more covert forms of control through international financial institutions.