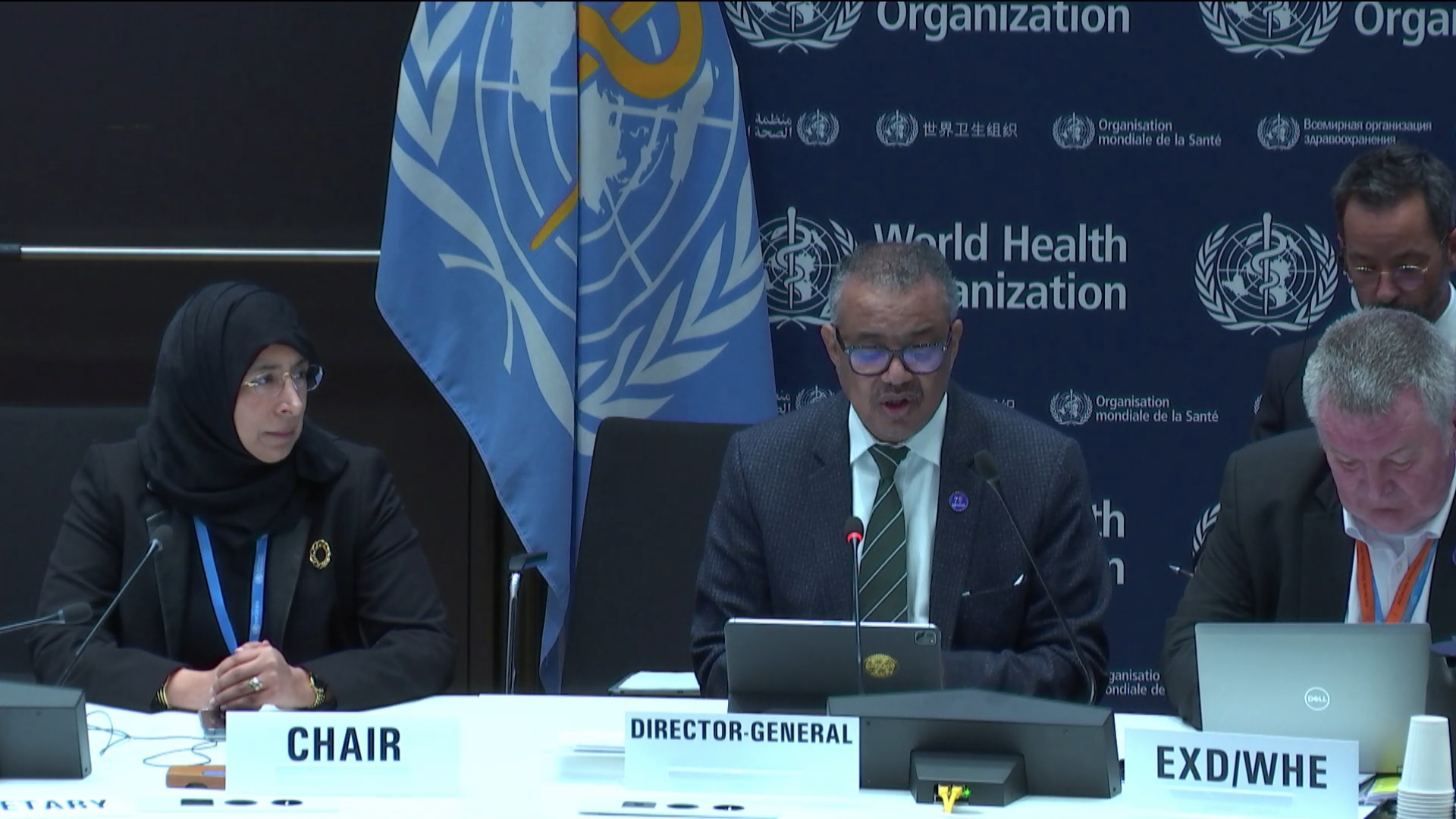

The World Health Organization (WHO) Executive Board’s 154th session, which began on January 22, is set to conclude on January 27. As its members prepare the agenda for the upcoming World Health Assembly (WHA) in May, discussions are expected to focus on topics summarized by WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus as “the five Ps”: promoting, providing, protecting, powering, and performing for health. Under this umbrella, the Executive Board (EB) is expected to touch upon everything from non-communicable diseases to anti-microbial resistance to the promotion of breastfeeding.

As always, the discussion will be heavily contextualized by current geopolitical events, including Israel’s continued war on Gaza, and topics that spark heated exchanges between WHO members, like the labeling of sexual and reproductive health rights as a political, rather than a technical issue.

During the first day of the session, the EB zoomed into the Pandemic Treaty, a long-awaited mechanism which should guide countries through future pandemics, building upon the lessons learned during COVID-19. The document is supposed to be finalized on time for the WHA to discuss it in May. Yet concerns have been voiced about potential delays, including by the WHO Director-General.

Tedros urged those in the room not to let the opportunity to finalize a Pandemic Treaty slip away, and to double their efforts in finding solutions which everyone can live with. While the pandemic has made perfectly clear that a global response to future emergencies must be rooted in solidarity and international cooperation, not too much of that spirit has been transferred to the negotiations on the treaty. Similar concerns apply to the ongoing process of revisiting the International Health Regulations (2005), which will focus on equity in its upcoming 7th meeting from February 5-9 2024.

High-income and low-and-middle-income countries have often found themselves at odds. While those in the Global South have been strong advocates of a document that would allow sharing of knowledge and resources, including pathogens, the Global North mostly remains loyal to protecting the existing intellectual property framework, strengthening pandemic surveillance infrastructure, and the interests of pharmaceutical companies.

The delegates taking part in the Executive Board discussion reiterated that they were determined to get a Pandemic Treaty proposal on time for the 77th World Health Assembly. Yet, it remains to be seen if they will be able to resolve this crucial difference in approach on time.

Read more | Pandemic Treaty continues to negate principles of equity and justice

Most of the reports that will be taken up by the EB should inspire the same sense of urgency like the one Director-General Tedros is calling upon in the discussion on the Pandemic Treaty. Everything from the global TB response, maternal health, the WHO’s increasing workload in humanitarian emergencies and conflict-affected settings, to infant nutrition and mortality, point to the fact that WHO’s members find themselves in a grim place.

The way out, illustrated throughout the Board’s agenda, is building responses based on equity and solidarity. Despite discussions within the past year in the negotiations for the pandemic treaty and political declarations at the UN General Assembly, there has been limited progress in enhancing the understanding of health equity or devising effective strategies to achieve it. The persistent dynamic reveals that certain developed nations continue to leverage their power to uphold the existing status quo, neglecting the urgent concerns raised by developing countries in their pursuit of equitable solutions.

Discussions on equity will continue under virtually all EB agenda items, including the one about Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Despite UHC’s shortcomings, the WHO Secretariat and member base continue to pursue it. Recent data indicates that 2 billion people faced catastrophic health expenditure in 2019 — not quite the financial protection that UHC was supposed to deliver.

“Emerging evidence shows increased financial hardship, especially among the poorest, with an uneven recovery post 2020/2021. A notable concern is the higher spending on national debt over health in developing countries,” the People’s Health Movement (PHM) stated in a policy brief published ahead of the EB meeting.

At the very least, this should be taken as a warning sign and nudge the WHO to consider other frameworks for achieving Health for All, including the Comprehensive Primary Health Care model from the Alma Ata Declaration. Instead, UHC will probably be given another round. This will certainly include a discussion on finance mechanisms for the improvement of UHC outcomes, like the Health Impact Investment Platform – which will continue reshaping the funding in a project-based manner, opening the door to even more indebtedness through the participation of investment banks.

Finances will be another ongoing discussion throughout the EB sessions. In addition to considering the Health Impact Investment Platform, members will also look at WHO’s core financing model and financial support for the new 14th General Program of Work (GPW). Recent changes attempted to increase assessed contributions from WHO members, which would allow the agency more flexibility and security in planning.

Another topic to follow when it comes to WHO’s finances is the investment round, a replenishment mechanism intended to allow the agency to raise earmarked funds. As pointed out by civil society organizations at the time when the approach was announced in May 2023, pursuing this financing model is likely to lead to even more influence of non-member donors on WHO’s priorities.

Additionally, there is a good chance that such an investment round will not even meet the set targets, causing additional headaches to the WHO Secretariat. “The three risks with the greatest impact and probability are: (a) the financial risk of not meeting the target; (b) the reputational risk of the investment round being portrayed as a failure; and (c) the structural risk of WHO’s resource mobilization approach not being optimized for an investment round,” PHM said in its commentary.

Read more | A replenishment mechanism for WHO?

Overall, the funds pooled by WHO remain short of what is needed, leaving enough room for partnerships like Gavi, or organizations like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to exert influence over WHO’s work. A similar lack of funds applies to the GPW, which does identify key factors that the world’s leading health agency should be able to address — including climate change, war, and displacement — yet the vision is not accompanied by an adequate financial structure.

Climate and health justice activist Andrew Harmer recently noted that the funds planned for the new GPW do not differ in a significant way from the current budgets. Considering the ambitious goals set and the fact that the money that was available until now was not really enough to achieve all the aims, expectations in the plan beg the question of how activities are going to be implemented if not by increasing reliance on sources outside the WHO membership.

The same non-state actors seem to be allocated a more significant role in the shaping of the plan itself. “Under the guise of inclusivity, non-state actors (which include civil society groups, but also the commercial and pharmaceutical sectors, the banking sector and partnerships such as GAVI) are being given an opportunity to influence WHO’s long-term strategy documents,” says Harmer.

To counter such influence, it is crucial for WHO members to fulfill their obligation to pay assessed contributions, as well as to increase those contributions in line with inflation and the organization’s needs.

In addition to that, PHM suggests implementing precise mechanisms based on existing tools, like the Framework of Engagement with Non-State Actors, and inviting broader participation from grassroots initiatives. Particularly in addressing health and climate change, planning done in cooperation with people’s initiatives is crucial, emphasizing the strengthening of community health partnerships and the involvement of health workers in climate change response strategies, aligning with the Alma Ata Declaration.

Member states could promote policies for better health outcomes, including addressing social determinants of health and allocating more significant finances for public services through progressive taxation. They could also choose to put an emphasis on opening more space for participation to groups representing people’s interests, rather than corporate priorities. However, the current agenda appears to lack substantial lessons learned from recent experiences, raising doubts about the prospects for such policies—at least for now.

People’s Health Dispatch is a fortnightly bulletin published by the People’s Health Movement and Peoples Dispatch. For more articles and to subscribe to People’s Health Dispatch, click here.