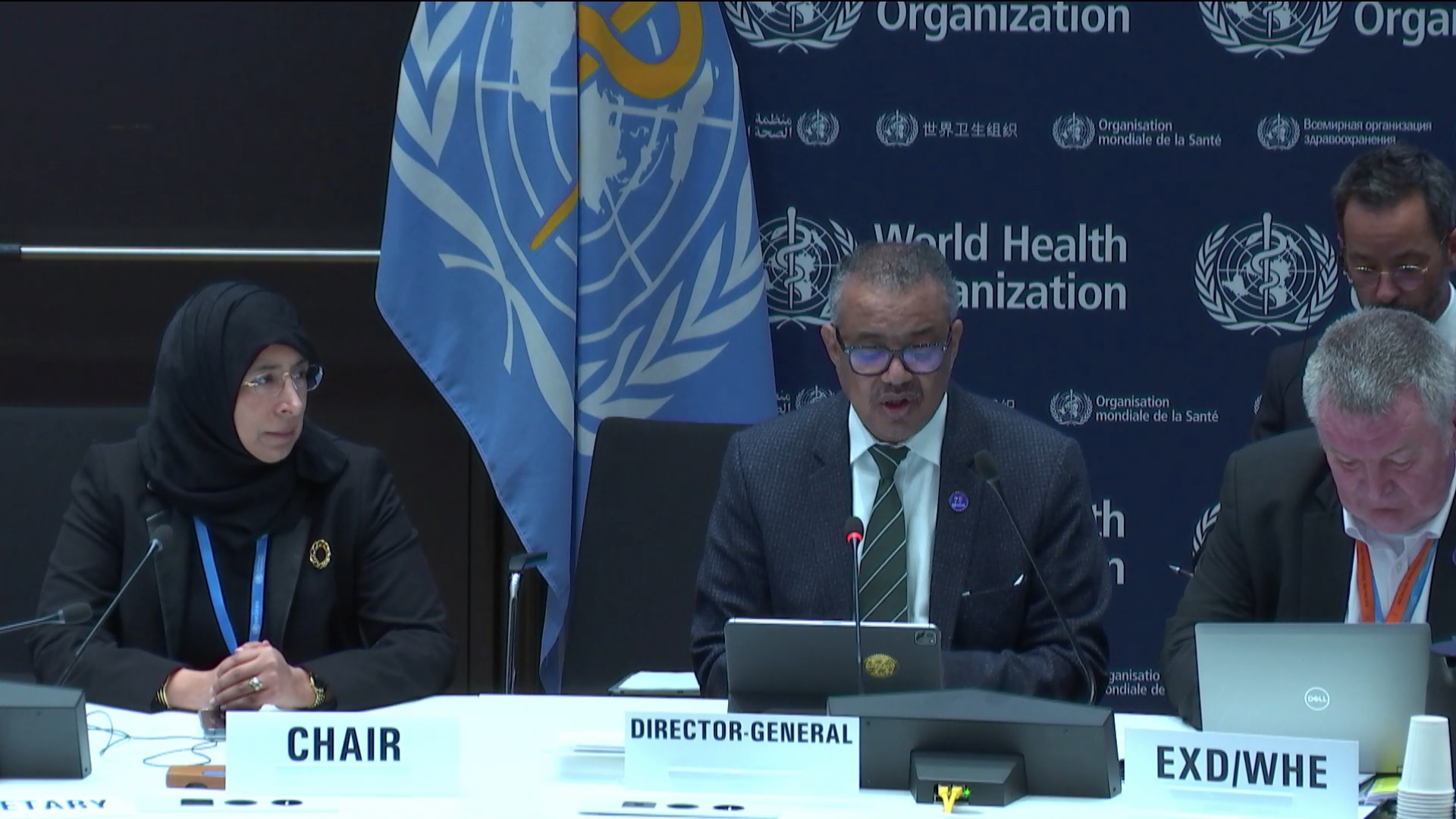

The 154th Executive Board (EB154) meeting of the World Health Organization (WHO) began on January 22, 2024, with a new agenda titled “Economics and Health for All.” In the coming period, WHO members will deliberate on proposals outlined in a first report published by the WHO Council on the Economics of Health for All in May 2023.

Established at the close of 2020, the council, led by distinguished economist Professor Mariana Mazzucato, comprises 10 female economists and health experts who spent two years developing a strategic plan to prioritize “Health for All” in economic considerations. The establishment of this Council was evidently due to the unprecedented socio-economic crisis sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic. This crisis has challenged global stability and unity, highlighting the inseparable link between health and the economy. A new, fresh take on the global economy was urgently needed.

What’s in the report?

The Council’s report emphasizes prioritizing human and planetary well-being over economic growth, restructuring innovation and financing systems for equitable health access, and bolstering government capacity for effective healthcare delivery. These pillars support 13 recommendations aimed at reshaping economic practices to achieve universal health goals through collaborative efforts across sectors, acknowledging the interdependence of health and the economy at all levels. The thirteen recommendations advocate for: valuing health as a long-term investment; enforcing health as a human right; prioritizing planetary health; adopting stable financing approaches; ensuring proper funding and governance for WHO; redrawing finance architecture for equity, using broader metrics beyond GDP; fostering public-private alliances; designing knowledge governance for equitable access; aligning innovation with health goals; promoting whole-of-government approaches; investing in public sector capabilities; and fostering transparency and public engagement for accountability.

Promising recommendations, yet lacking immediate practicality

The report’s launch garnered success, and was hailed as a “radical redirection” in economic thought. While it underscores the urgency of reshaping the perception of health services as investments rather than costs, it falls short in exploring concrete implementation strategies. Recognizing the intricate link between economic activities and health outcomes, the report advocates for bold measures such as excluding health investment from sovereign fiscal deficits and suspending debt repayments during health crises. However, it neglects to analyze the root causes of health, inequality, and climate crises, posing a risk that its recommendations remain symbolic without a clear theory of change. Although proposing reforms like intellectual property regulation, the report lacks actionable strategies for societal transformation.

The idea of a ‘Dashboard for a healthy economy’ suggests optimism in leveraging information for change, yet it lacks a mechanism for altering political dynamics. The Council’s report, along with that of the Secretariat, fails to address the hurdles limiting the WHO’s ability to progress, such as the United States’ repeated denials of WHO’s mandate and the restrictive policies of high-income countries. For instance, during the week of the Council’s report release, reports surfaced alleging that the US threatened to withhold funding from the WHO unless its provisions regarding “earmarking” contributions were integrated into the decision on the replenishment proposal. This action undermined the resolution’s aim of boosting the WHO’s urgent need for flexible funding, crucial for fulfilling its mandates. What is needed is further analysis on the root causes of interconnected crises, barriers to implementing recommendations, and consensus-building for international debt relief.

Member States’ perspectives

During EB154, the Secretariat report (EB154/26) laid the groundwork for WHO members’ official responses to the Council’s work. While many expressed warm appreciation for the efforts, others approached the matter with caution. Morocco emphasized the imperative of prioritizing social justice. Togo commended the focus on enhancing public capacity in the recommendations, and Brazil called for increased consultation between the WHO and its members. The US raised concerns about the potential high costs associated with the proposed approach. China advised careful implementation to prevent exploitation by commercial entities and advocated for greater consideration of suggestions from the Global South by the WHO.

Belgium and Namibia made notable contributions to the discussion. Belgium commended the report for challenging the assumption that government intervention stifles pharmaceutical innovation, while the UK cautioned the WHO against undermining the intellectual property rights framework. Namibia emphasized the urgent need to confront the unfairness of the global financial system. Bangladesh underscored the necessity of rectifying the economic system, which perpetuates unequal dividend distribution and widens health disparities. Namibia highlighted the alarming doubling of debt ratios in Sub-Saharan African countries over a mere decade, urging the WHO to engage with international financial institutions to address the debt crisis and bolster health financing.

The report recognizes the unavoidability of WHO’s collaboration with institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, but it overlooks their historical failure in preventing or addressing debt crises and the societal and environmental degradation stemming from their loan programs and neoliberal policies. Given the unlikely prospect of these institutions changing their practices, it is imperative for the Council to provide guidance on how WHO can collaborate with international financial institutions to achieve its ambitious goals without compromising on its principles.

Does the Council’s progress align with the ambitious goals of the Alma Ata Declaration?

In his closing remarks, Dr. Bruce Aylward, Assistant Director-General of the WHO, emphasized the Council’s mission of bridging the gap between economy and health to realize health for all as envisioned in the Alma Ata Declaration. While the Council’s report marked a radical step forward, it fell short of the ambitious 1974 UN General Assembly resolution referenced in the Alma Ata Declaration as the necessary first steps toward health for all, which sought to fundamentally transform the status quo in the global economic system. Contained within were a series of proposals aimed at improving the position of developing nations in the global economy. These included granting States control over their natural resources, regulating transnational corporations, facilitating no-strings-attached technology transfers from north to south, providing trade preferences to southern countries, and forgiving certain debts owed by southern states to northern counterparts.

People’s Health Dispatch is a fortnightly bulletin published by the People’s Health Movement and Peoples Dispatch. For more articles and to subscribe to People’s Health Dispatch, click here.