Since April 28, formal and informal workers, students, and unemployed youth have been at the forefront of a vast social uprising in Colombia, fighting to stop and revert a new wave of neoliberal reforms pushed by the government of Ivan Duque. Among the announced changes that sparked the protests are conservative tax reforms and regressive health reforms, with negative impacts for patients and healthcare workers. Unsurprisingly, health workers have supported the protests that have drawn hundreds of thousands to the streets for weeks in the midst of the deadliest COVID-19 wave so far.

The tax reforms (which were later dropped) were presented as an effort to ease pandemic recovery. But they would actually have meant higher taxes on food for the poor, and benefits for the rich. On a similar line, the proposed health reform would have led to increased commercialization of an already highly marketized healthcare system. The suggested changes foresaw mergers between public and private health institutions and increased the role of Health Insurance Entities (EPS). EPS have been criticized for reducing access to care. The announcements have been met with dismay by most of the population, especially given that according a report by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) published on April 29, 2021, 21 million people, or 42.5 percent of the population, live in poverty, an increase of 6.8 percent from last year. Seeing that the burden of the economic recovery would have been concentrated on the shoulders of the dispossessed soon led to a popular response.

The most recent proposed reforms were merely the tipping point. As movements and organizations that have been mobilizing have pointed out, the social uprising is a response to decades of neoliberal policies, deepened economic inequality, and a continued brutal war against the people that has seen over 1,000 human rights defenders and social leaders be assassinated by state and paramilitary forces since 2016.

Deteriorated access to healthcare services and working conditions

Access to healthcare in Colombia has effectively been reduced by introducing a healthcare market and private intermediaries, the EPS. In addition to reducing access for patients, past reforms have had an extremely negative effect on health workers’ rights.

According to research by Mauricio Torres-Tovar from the National University of Colombia and the People’s Health Movement, working conditions in the healthcare sector in Colombia have deteriorated since the introduction of the neoliberal reforms in the mid-1970s, and particularly in the early 1990s. During this time, jobs in healthcare have been informalized and working conditions made worse under the influence of the EPS that, by controlling the finances, subordinated health institutions to a market logic, foregoing accessibility of care for administrative benchmarks.

Informalization has brought along longer working hours, less job security, and less income for health workers. It is estimated that over 50% of general practitioners and 79% of specialist doctors across different types of health institutions in Colombia are currently employed through third party contracts, says Torres-Tovar. The same is true for around 28% of nurses. Independent contracts cover everything from professional honoraria to service contracts, but what they have in common is that they are fixed-term and do not provide for any benefits for workers except for a basic salary – meaning that many health workers do not have access to sick leave, or employer’s contributions to retirement funds, and have less control over the amount of hours they are required to put it.

Similarly to what happened in the rest of the world, already inadequate working conditions in health care deteriorated with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the first case was diagnosed in Colombia, at least 7,552 health workers were infected with the virus, and 51 of them died. Among those infected, almost half (47%) were nurses and nursing assistants. One of the causes of high infection among health workers was the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE). The shortage was worse in private settings, a common trend across the world.

Health workers support the protests

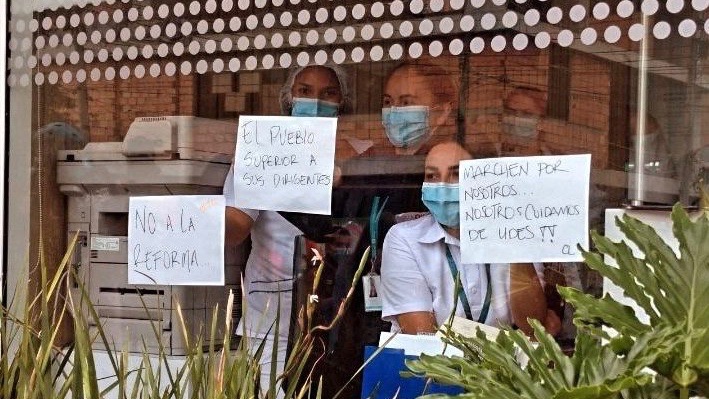

It does not come as a surprise, then, that health workers supported the popular uprising in different ways, including participation in the National Strike Committee (CNP). The committee brings together national trade union centers, as well as several specific trade unions including those of teachers and health workers, and several students’ associations. Along with several other key social movement platforms, the CNP issued the call for the first strike and has continued organizing mobilizations throughout the 7-week long, ongoing uprising.

The government tried to discourage participation in the demonstrations by arguing that the mobilizations would increase the number of COVID-19 cases and throw the already exhausted health system over the brink. Groups of nurses and doctors, like those in the western city of Tulua, took the side of the protesters. Although over 90% of ICU capacities in Tulua were full at the time, the health workers reassured the public that they continue to support the protests. One of the groups was particularly explicit when they shared an update on their social media channels, saying they have been dedicated to caring for those who contracted COVID-19 on parties, and they would care with double dedication for those who might get it during a protest.

Health workers did end up seeing more patients in the hospitals, but instead of being COVID-19 cases, they often were victims of the violent state repression. According to human rights organization Temblores, within the last 7 weeks there have been 1,468 victims of physical violence, 70 victims of eye related injuries, 215 victims of injuries with firearms, 28 victims of sexual violence, 41 cases of respiratory affectation from tear gas and other alarming figures.

Healthcare workers have been working both in the hospitals and in the streets to attend to injured protesters. First-aid and street-medic stations have been set up by healthcare workers at major protest sites to be able to rapidly attend to injuries especially given that police repression often can cause a delay in the arrival of emergency vehicles.

The wave of police violence against protesters in Colombia has been called out repeatedly by human rights organizations. Recently, the CNP has also met with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to report on the government’s infringement of human rights during the protests.

Nevertheless, the government continues to avoid more significant discussions about the protesters’ demands. In addition to a brief stint of negotiations with the CNP, abandoned by the committee because of stalling and obstruction by the government, Duque has only agreed to short-term and cosmetic interventions. But there is still no mention of progressing toward the requests that would improve living conditions for a large part of the population, such as a guaranteed basic income or equitable access to healthcare.

Meanwhile, support for the protests remains strong, indicating that the mobilizations will continue. Given that the demonstrations have already led to a number of remarkable successes, most notably the cancellation of both the health and tax reforms, it is possible that in the coming weeks they will achieve even more.