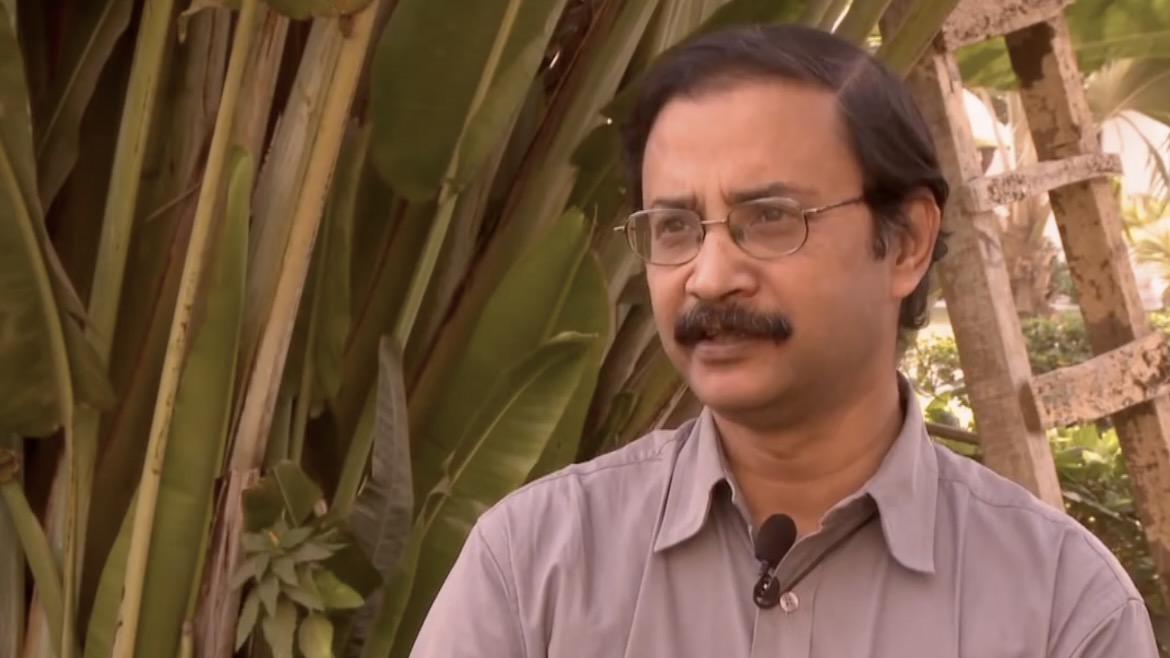

Amit Sengupta (1958 – 2018) was the Associate Global Coordinator and co-founder of the People’s Health Movement. He was also a member and contributor to other platforms both globally and in India, including the All-India People’s Science Network and Jan Swasthya Abhiyan. As a dedicated activist and a doctor, Amit fought for universal health care, including access to medicines.

Amit played a key role in many of PHM’s programs, including Global Health Watch and WHO Watch, through which he came to know and inspire many young health professionals and health activists. His effect was the same on more experienced activists, with whom he worked on the organization of several People’s Health Assemblies. Among other things, Amit covered the changes that international health institutions, particularly the WHO, went through from the Declaration of Alma Ata in 1978.

On the occasion of World Health Day, we bring you an excerpt from one of his articles on global governance of health, which can be found in full in the book Political Journeys in Health.

The almost universal application of policies that promote integration of the globe through trade in goods and services and liberalized flow of finances—loosely termed ‘globalization’—has also necessitated the development of fairly elaborate global structures of governance. In the health sector this manifests itself as global health governance, i.e. global structures that attempt to govern issues related to health that transcend national boundaries.

Coordination and cooperation between countries on matters of global health (or international health, as it was then known) have existed since long in the past. Some of the earliest concerns had to do with those related to the spread of infectious diseases. Over a period, this led to the adoption of some of the first international regulations related to health, such as quarantine measures and mandatory norms on vaccination.

In earlier centuries, international regulations related to health were structured to protect the interests of the colonizing powers. When the era of colonization became history, international

regulations were structured in a more egalitarian framework. In the health sector, this was reflected in 1948 with the birth of the WHO and its stewardship of global health policies. It was also reflected in the International Labor Organization (ILO), promoting global standards on occupational safety and health protection. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), adopted in 1947, and the International Sanitary Regulations (adopted by the WHO in 1951 as the International Health Regulations) included provisions aimed at balancing the interests of health and trade. The WHO promoted global efforts to improve health in developing countries, through such strategies as promoting the right to health, Health for All, the Essential Drugs List, and the International Code on the Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes.

In recent decades, issues under the purview of global health have moved far beyond the physical spread of diseases. Since the early 1980s, the global architecture of governance, trade and economics has come to be informed by globalization, and consequently national decision-making and national policies are often subject to global influences. This is true in the health sector as well, and the advent of globalization marks a shift in institutions and structures that govern health at a global level.

The use of the term global instead of international, when discussing issues of health that go beyond national boundaries, is in itself significant. International health held the connotation

that national concerns and policies formed the bedrock of policies about supranational issues, while global health appears to start from the premise that global issues largely supersede national policies, concerns and priorities.

It is possible to identify four major developments in the last three decades that have had a profound impact on the structures and processes of global health governance. The first is the emergence of the World Bank as a major player in the arena of health governance in the 1980s, which has been discussed extensively in the previous chapter. Second, the growing importance of global trade in international relations, and its impact on health in different situations across countries, has led to a major role for the World Trade Organization (WTO) and regional and bilateral trade agreements in global health. Third, private foundations (such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation) have entered through public-private partnerships and other avenues, to become big players in global health issues. The fourth development is the demise of the WHO as the premier organization in the area of global health governance. While all four are linked, each has arisen in specific contexts that are analyzed below.

The WTO steps in

Since 1995, the WTO has become the major international forum for debate and resolution of conflicts in the area of major health-related policies or policies that have an impact on health.

The WTO’s ability to intervene in global health issues is of a much higher order than that of the WHO, as the WTO agreement is a binding agreement with clear commitments made by contracting parties. The WTO imposes a ‘rules-based system’ and adherence to these rules is exercised through a dispute settlement mechanism. The dispute settlement mechanism allows member countries to use trade sanctions to enforce rulings against member states that fail to comply with its decisions. In contrast, the WHO does not have mechanisms that can force member countries to abide by its decisions. Thus, for example, health-specific legal agreements that have been endorsed by member countries in the WHO—such as the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control or the revised International Health Regulations 2005—do not contain compulsory dispute settlement and enforcement provisions.

The governance of global trade, and its impact on health governance, now go much beyond the WTO. The failure of the WTO to accommodate the interests of all countries, and the repeated and visible collapse of ministerial negotiations, has prompted developed countries to look for other channels to promote global trade. Consequently, regional and bilateral trade agreements are an increasingly important part of trade and health governance. In many cases, these agreements do not include the flexibilities and health safeguards available under the TRIPS agreement and can impose onerous terms in other areas as well.

Global public-private partnerships

A new family of initiatives that have a major impact on global health governance are global public-private initiatives (GPPIs). In the past two decades several hundred such initiatives have been launched, with over 100 working in the health sector alone. The genesis of these GPPIs is fairly recent, dating back to the 1990s. GPPIs came to be developed based on an understanding that multilateral co-operation in the present globalized world could no longer adhere to the older principle of multilateralism that primarily involved nation-states. Global partnerships were, thus, imbued with a new meaning, that involved not just nation-states, but also other entities, including, prominently, business organizations such as pharmaceutical companies that work through the medium of the market. These new partnerships were further promoted by philanthropic foundations, largely located in the United States, such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Partnerships with the private sector and civil society are thus held up as the way to achieve what governments and the United Nations cannot manage alone.

GPPIs need to be viewed in the context of an attempt to address the obvious failure of the market to deliver services and goods where most required, i.e. to the income- and resource-poor, while at the same time staying within the boundaries of neoliberal economic policies. They address what neoliberal economists describe as ‘market failures’, but at the same time do not question the fundamental faith in the ability of the market to regulate the global flow of goods and services.

While there has been no systematic evaluation of the impact and viability of GPPIs in the health sector, there have been several evaluations of specific GPPIs. Based on these evaluations some major concerns are beginning to emerge. The gross under-representation of the global South in the governance arrangements of GPPIs, coupled with secretariats often being located in the North, is reminiscent of imperial approaches to public health. GPPIs are seldom integrated with the health systems of the recipient countries. As a consequence, programmes are seldom sustainable particularly after a GPPI runs its course or withdraws support. GPPIs can allow transnational corporations to exert influence over agenda-setting and political decision-making by governments.

The World Health Organization: time to reclaim its mandated role

Another disturbing feature is that the WHO’s leadership in global governance issues has been seriously compromised with the usurpation of its mandate by multiple agencies—the World Bank, the WTO, GPPIs, etc. Increasingly, there is a tendency to characterize the WHO as a ‘technical’ agency that should concern itself only with issues related to challenges of communicable disease control and the development of biomedical norms and standards.

The WHO faces three key challenges, related to its capacity, legitimacy and resources. Its legitimacy has been seriously compromised because of its inability to secure compliance with its own decisions—which are reflected in the various resolutions passed at the World Health Assembly. Developed countries which contribute the major share of finances to the functioning of the WHO have today a cynical disregard for the ability of the WHO to shape the global governance of health. They see the member state driven process in the WHO (where each country has one vote) as a hindrance to their attempts to shape global health governance, and prefer to rely on institutions such as the World Bank and the WTO, where they can exercise their clout with greater ease.

As with many other UN organizations, the WHO’s core funding has remained static because of a virtual freeze in the contributions of member states. Its budget amounts to a tiny fraction of the health spending of high-income member states. In addition, a large proportion of the WHO’s expenditure (about 80%) comes in the form of conditional, extra-budgetary funds that are earmarked for specific projects by contributing countries. For example, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is today one of the largest single funders of the WHO, contributing more than most member countries. The executive board of the WHO (in January 2011) discussed a paper by the organization’s secretariat that talked about the crisis in the WHO’s finances. Today, the WHO is sustained through a financing system that undermines coherent planning and which forces WHO departments and divisions to compete with each other (and other organizations) for scarce funds. The consequence of this is that health priorities are distorted and even neglected to conform with the desires of donors and the requirement to demonstrate quick results to them.

The WHO is in danger of being compromised because of conflict of-interest issues that arise out of contradictions between the constitutional mandate of the WHO and the interests of individual donors.

As a consequence of the above, the WHO is inadequately equipped to reclaim its leadership role in global health governance. At the global, regional and country level, WHO offices are weak and inadequately resourced, compared to the country-based offices of other international organizations and development agencies.

Need to restructure global health governance

Clearly, the global governance of health is a minefield of contradictions. It is shaped by multiple agencies and by multiple interest groups. In a globalized world this is evidently a cause for concern. While tools designed to mitigate ill health and disease are now available as never before, access to such tools is a bigger problem than ever. A nation-state-driven process, premised on principles of equity, justice and sharing, is an urgent requirement if the global governance of health is to be restructured and this problem addressed. National governments, especially from the global South, need to take the lead in rescuing global health governance from the clutches of sectional interest groups.

This article was published in Political Journeys in Health (LeftWord Books, 2021) and in the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics (vol. 8 no. 2, April-June 2000). The original version was edited for length.

Read more articles from the latest edition of the People’s Health Dispatch and subscribe to the newsletter here.