At the start of this year, days after the inauguration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva as the Brazilian president, an event shook the nation. On the January 8, thousands of supporters of former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro stormed the halls of power in the country’s capital, Brasilia. They were dressed in yellow and green, the colors of the country’s flag and the national football team’s official shirt, itself a disputed symbol as it was appropriated by the far-right “Bolsonaristas” in recent years. The protesters invaded the “Three Powers” – Planalto Presidential Palace, National Congress, and Federal Supreme Court. Met with little resistance from the military police, the Bolsonaristas broke through the barricades and went on a destructive spree. Among the wreckage were 700 pieces of artwork, decorations, and furniture that were vandalized or destroyed. The invaders ransacked the buildings, which themselves are works of art, designed in the 1950s by one of Brazil’s most famous architects and communists, Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012). These buildings in the heart of the new political center of the country were monuments to a national project, of a vision for a modern Brazil.

But looking back on the day, what were the Bolsonaristas hoping to create from the destruction? And reflecting on the last four years, what has been the project of Bolsonarismo? There were three pieces of artwork found among the ruins that give some insight into these questions, and the possibilities that Lula’s return holds.

The protagonists of history and art.

The centerpiece of the presidential palace’s main hall is As Mulatas (“The Mulatto Woman”), painted in 1962 by the great modern artist, Emiliano Di Cavalcanti (1897-1976). Though much of the reporting has focused on its monetary value, estimated at US$1.5 to 3.8 million, it is impossible to quantify cultural loss.

Di Cavalcanti saw artmaking as an act of political participation, and his work represented the underrepresented sides and contradictions of the Brazilian reality. As a key organizer of São Paulo’s Modern Art Week in 1922 that elevated Brazilian culture and modernity onto the international stage, he joined the Communist Party of Brazil in 1928, and was jailed more than once for his political affiliation.

Reconciling the language of the European avant-garde with the Brazilian context, Di Cavalcanti’s work was focused on the national question, but with his artistic eye turned to the workers, people of the favelas, women, and black people as the protagonists. As its title suggests, As Mulatas features women of mixed ancestry. It asks by whom and for whom is Brazil built, in a country where 56.1% of its 212 million inhabitants self-identify as being black or of mixed ancestry, and who have been historically denied access to political power and cultural representation. This painting was slashed seven times by Bolsonaro-supporters in the invasion.

In September 2022, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and several Brazilian partners, including the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST), launched the visual art exhibition, 200 years of an interrupted nation | Art as a form of denunciation and resistance. 28 artworks were created as a reflection on the dual anniversaries of 200 years of Brazilian independence and the centenary of the Modern Art Week, which, “despite its limits,” writes the organizers, “tried to represent the true protagonists of a nation that insisted on being born: The Brazilian people, historically marginalized and invisibilized.” Bolsonarismo represents a continuation of this “interrupted nation,” and its insistence on cultural destruction is not an accident, but epitomizes its political project.

Two great fires.

I moved to Brazil in May 2018, shortly before the election of Bolsonaro. A lawfare coup had already been underway for at least two years, which led to the impeachment of Workers’ Party (PT) president Dilma Rousseff in 2016 and the imprisonment in April 2018 of then ex-president Lula for 580 days on unfounded corruption charges.

My first year in Brazil was bookended by two great fires. The first was the tragic fire of the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro, where most of the 20 million artifacts were destroyed. In response to this fire, Bolsonaro said, “It already caught on fire, what do you want me to do?” When asked about the museum’s chronic underfunding that led to this fire, Bolsonaro responded with mockery, showing his outright disdain for the country’s cultural heritage and the role of art and culture. Very symbolically, he made it one of his first tasks to dissolve the Ministry of Culture upon assuming his presidency. Brazil’s far right, galvanized around Bolsonaro, is a project of violent historical erasure and cultural destruction, in a physical and subjective sense.

The second fire. On Monday, August 19, 2019, I walked out of the office to be met with the ominously and prematurely blackened skies of São Paulo. It was only 3:30pm, hours before nightfall. Winds had carried smoke from the Amazonian wildfires, 2,700-kilometers away. Bolsonaro had encouraged the illegal burning, serving the interests of agrobusiness and his financiers, at the expense of the planet, the people, and world heritage. During Bolsonaro’s presidency, over 33,000 km2 of the Amazon, the lungs of the planet, was destroyed – equivalent to the size of Taiwan island – and deforestation rates increased by 59.5%, outdoing any other presidency since satellite measurements began in 1988.

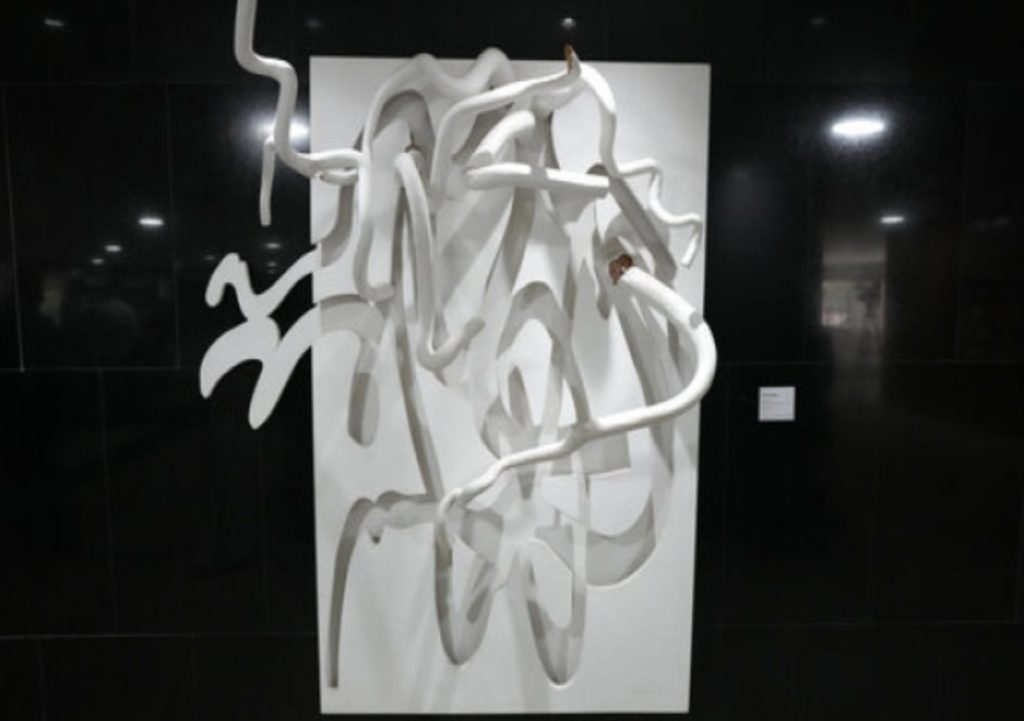

It may be a cruel irony that one of the sculptures vandalized in the Brasilia invasion was Galhos e Sombras (“Branches and Shadows”) by Frans Krajcberg (1921-2017), a Polish-born Jewish artist who immigrated to Brazil after most of his family had been killed in the Holocaust. A defender of the Amazon and as an act of protest, Krajcberg made sculptures using burnt wood from illegal forest fires. He went to the Amazon forest several times, gathering materials for his work while bearing witness to these environmental crimes. Krajcberg’s own family fell victim to Nazi fascism, and decades later, his work and the subject of his work – the Amazon – are today’s victims of Bolsonarismo. History may repeat itself, first as a tragedy, as Marx said, but the second time remains a tragedy still.

At the COP27 in Egypt, still weeks before he officially reassumed his presidential post, Lula made a moving speech, committing to net-zero deforestation in the Amazon until 2030. “Brazil is back,” the audience chanted. If Krajcberg was still alive, we know on which side he would stand, and for which project for the country he would support.

Lula arrived at the Planalto Palace to receive his green-and-yellow presidential sash, which was supposed to be handed over by Bolsonaro, who instead was found strolling in the suburbs of Orlando. Lula arrived hand-in-hand with the Brazilian people – indigenous, black, and poor people, women and children from the periphery, and people with disabilities. Photographed, illustrated, and circulated countless times since, this symbolic act has already become an iconic image. Like Di Cavalcanti’s paintings, this political act reinserts the people – the workers, poor, and dispossessed – as the protagonists of history and politics. This political act is also a battle of ideas, a battle over culture, emotions, and the image.

Days later, Bolsonaristas, and their “project of national destruction” as Lula had called it, invaded that same palace. Ironically, one of the works vandalized and left littered on the ground was Bandeira do Brasil, a painting by Jorge Eduardo (1936–) of the national flag – the very symbol that Bolsonaro supporters had appropriated and distorted for their ultra-right cause. But what message did they want to say in this act? To whom does this symbol belong?

On inauguration day, a fifty-meter Brazilian flag was carried by hundreds of people as Lula proclaimed, “Our message to Brazil is one of hope and reconstruction.” What the Bolsonaristas tore down during the invasion, and over the last five years, is being raised and reclaimed by the people. “To create,” as Di Cavalcanti said nearly a century ago, “is above all to give ideal substance to what exists.” And the people will continue to create from the embers of the great fires, and to give substance to new national project in Brazil’s own image.

Top: Bandeira do Brasil (“Brazilian Flag”) (1995), Jorge Eduardo (reproduced from Twitter)

Bottom: 50-meter Brazilian flag unfurled at Lula’s presidential inauguration (reproduced from Twitter)

Tings Chak 翟庭君 is the art director and a researcher of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, and a co-founding member of Dongsheng News. She is currently pursuing a doctorate at Tsinghua University and lives in Beijing.