“I feel Latin American in every country, but without ever resigning myself to illusions of my land, Aracataca, to which I returned to one day and discovered, that between the reality and the nostalgia, was the raw material of my work”

– Gabriel García Márquez, The Fragrance of Guava, 1982

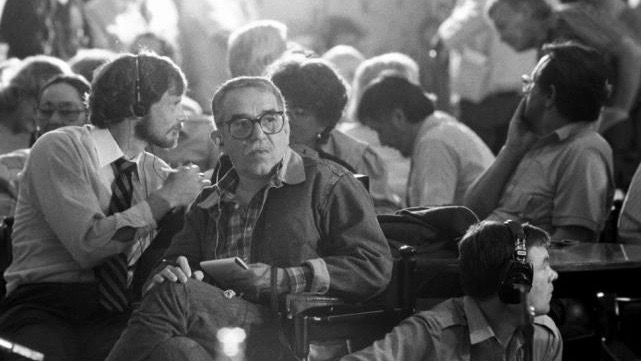

Sometimes what is obvious hides what is important. Gabriel García Márquez is best known as the craftsman par excellence of the genre ‘magical realism’, rather than his profound passion for the profession of journalism that led him to traverse—with the eagerness of a chronicler and a vallenato rhythm in his step—countless cafes, newsrooms, and continents.

Gabo, or Gabito, as he was known to his friends in Aracataca, a town camouflaged among the banana plantations of Colombia’s Caribbean coast, produced a journalism that few recognize, journalism militantly committed to a national and global context. International affairs, and in particular the people that rose up against US imperialism, were the ink for his pen. Instead of hiding behind the sudden fame produced by the publication of ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ in 1967, over the years he became radicalized and refined his writing with an acidic humor indebted to those brought up in that “village of twenty houses of mud and reed built on the shore of a river of diaphanous waters that rushed down a bed of polished stones, as enormous and white as prehistoric eggs.”

Crossing a huge diversity of literary and journalistic genres, García Márquez managed to hybridize both professions by deepening his political thought and extending his journalistic interventions to a range of spheres, stretching from reflections within a national and regional context, to international relations and the reality of other continents. The development of Gabo’s personal and professional life went hand in hand with the development of the twentieth century, meaning that many of the major, transcendental social and historical events in mankind’s history in turn became the fundamental building blocks of his own being: the fall of Nazism and fascism in Europe; the Bogotazo and the war between the liberals and conservatives in Colombia; the deployment of Colombian troops in the Korean War; the consolidation of the Soviet Union and the socioeconomic model of Eastern Europe; the triumph of the Cuban revolution; the dictatorship of Rojas Pinilla and Operation Condor in Latin America and the Caribbean; the development of what’s called the Cold War; the hegemonic anticommunist discourse; and the battles for national liberation on the African and Asian continents. All of this, amongst many other events, were key elements in the publications of the writer from Aracataca.

Born and raised in a humble family on the fringes of the Caribbean—with all that this implies including his revolutionary identification with that famous socialist island—García Márquez was, however, a pilgrim of the world. His passion to know the truth, that age-old fetish of journalists, led him to travel and engage with the reality of the different people that he met, and with that he constructed a committed, situated, and militant journalism, that until his last days, sought to create scenarios and platforms which many, many journalists from the continent could publish from without fear of censorship.

After passing through numerous towns and cities on the Colombian Caribbean coast, he finished his secondary school education in the Liceo Nacional de Zipaquirá, a hotbed for teachers schooled in Marxism, who taught Gabo and his school-mates about historical materialism, Leninist theory, and class conflict, not only in the classroom but in the playground. For our García Márquez, the journalist, his passage through Zipaquirá was decisive in his subsequent choice of writing as his way of life.

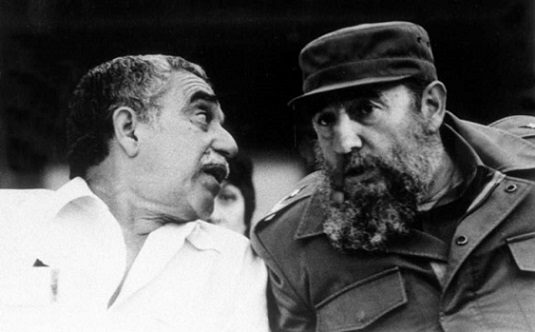

Despite having opted for a degree in Law at the National University of Colombia, the young Gabo decided to dedicate himself to writing stories and the occasional report for several newspapers in Bogotá, amongst them the newspaper ‘El Espectador’, that back then notably featured a generation of investigatory journalists. In that writing job, on April 9, 1948, in a Bogotá cafe a few blocks from where the Organization of American States (OAS) was formed and where mere hours before they had assassinated liberal leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, García Márquez interviewed the then Cuban student leader, Fidel Castro.

That day forever changed Colombia and Gabo became a protagonist in his own writings. With the assassination of Gaitán along with the political opinions that he held, Gabo’s first path to exile had begun. During the conservative government of Mariano Ospina Pérez and Laureano Gómez, García Márquez was censured and criminalized for his publications. Especially for his profound repudiation of the government’s decision to send a Colombian battalion to support the US during the Korean War. From that point on, his work was characterized by a particular concern for the role that North-American imperialism would play in the future of the Latin American and Caribbean continent.

During the de facto government of Rojas Pinilla, García Márquez would leave for Europe on a journalistic mission that was almost an obligatory exile owing to the dictatorship’s censure of his publications, and later, of the newspaper ‘El Espectador’ where he had been working at the time. So began a journey to Europe with the objective of covering the 1955 Geneva Summit between the governments of the Soviet Union, the United States, France, and the United Kingdom. Owing to his early training in Marxism and his permanent interest in international affairs, these meetings then took him on a passage across the European continent in 1957 to learn about the reality inside the Soviet bloc. He toured both Germanies, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, Ukraine, and the Soviet Union, and published a series of columns on the development of a socialist system within the framework of a capitalist world, including the contradictions, advantages, and difficulties of the countries in the Soviet bloc. In them, one can read a critical position in respect to dogmatism along with the necessity for socialism in Latin America to be its own socialism, one that takes account of the realities and necessities of our continent, and that should not be an “exported revolution” with formulas and manuals. However, despite his critical stance, he pointedly affirmed in ‘Militant Journalism’ (1978) that: “Never will I embark on a mission against the Communist Party, nor against the USSR, nor against China, nor against Cuba, nor against any other left party or group in any part of the world”. These chronicles would later be published as ‘Travels through the socialist countries: 90 days behind the Iron Curtain’ in 1978.

That immense homeland of deluded men and aged women, whose endless stubbornness is confused with legend.

From Europe, he returned to Latin America to deepen his journalistic engagement with his continent’s reality. He initially arrived in Venezuela in 1957, where he spent three years in which he was able to experience the insurrection against Marcos Pérez Jiménez on 23 January 1958. While there he wove together a strong web of solidarity with various Venezuelan movements, which inspired him in 1972 to donate all the money he was awarded for winning the Rómulo Gallegos prize for ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ to the Movement for Socialism (MAS), a splinter group of the Communist Party of Venezuela. Once again, part of his personal experiences and journalistic travels would be reflected in one of his works, in this instance ‘The Autumn of the Patriarch’, which was inspired by events in Caracas at the end of 1950s.

In January of 1959, he was invited with hundreds of journalists from the Latin-American region to the press conference Operation Truth, organized by Fidel Castro with the intention of making the reality inside of the nascent Cuban Revolution visible abroad. There, García Márquez became a correspondent for Bogotá and New York for the ‘Agencia Informativa Latinoamericana Prensa Latina’, which led to his intense persecution in the United States to the point of having to return to work for ‘Prensa Latina’ from Havana, Cuba: “They didn’t give me a visa to go to the United States and I didn’t want one; I believe that it is because of my political heritage that I was denied a visa to the United States, precisely because I was a correspondent for Prensa Latina in New York while the gusanos were landing in Playa Girón”.

In his time with ‘Prensa Latina’, Gabo worked together with other journalists from the continent, like the Argentines Rodolfo Walsh and Jorge Ricardo Masetti, with whom he shared visions of the present and future, and who were essential analytical elements in his map tracing the reality of Latin American and the Caribbean peoples that—year after year—was gaining greater importance and prominence in his journalistic career.

With his friendship now cemented with the leader of the Cuban Revolution, and a professional sensibility as well as humanistic ideal to write and investigate the hidden truths of the continent, García Márquez left for Mexico to build his new home there. This marked a period of political radicalization linked with socialism as a necessary project for the Latin-American region, which included his internationalist interpretation of Latin-American processes:

“I would like to establish [this] precedent, to open holes in the fiction of Latin-American nationalities. The export of revolutions defined our countries until the legal bottleneck of ‘non- intervention’ was invented. Bolivar fought and built his politics in Bolivia, San Martin kept climbing until his horse could go no further, Petión exported his independence from Haiti, while the federalist leaders of the past century walked from their homes in Mexico to Argentina. The Colombian general, Rafael Uribe Uribe, who did not win 32 wars but by every measure lost them all, once fought on the side of liberal Venezuela against the troops of his own country’s archaic regime.”

Later, during his years in Barcelona (1967-1975), García Márquez expressed in numerous public writings his repulsion to the Franco regime’s falangismo and fascist European traditions. In this period, Gabo, now consolidated as one of the principal exponents of Latin- American literature, began to make even clear the commitment of his pen to the popular causes of the world.

In 1978, he created ‘Habeas’ in Mexico, a Human Rights foundation in Latin America, that had the main objective of achieving freedom for the hundreds of political prisoners that had found themselves incarcerated by dictatorships. For this cause, García Márquez had already donated $10,000 of the prize money awarded by the University of Oklahoma for the creation of a fund for the defense of political prisoners in Colombia.

By this time, several of his colleagues had been victims of State terrorism, like his friend and colleague Haroldo Conti from Argentina, who in 1975 sent him a letter denouncing the atrocities and the persecution committed by the government of María Estela Martínez de Perón, where para-state repression was already taking place. This was a glimpse of the cruelty to come, as months later the dictatorial Military Junta began, who eventually detained and disappeared Conti on May 5, 1976. Years later, Gabo published the article ‘The last and bad news from Haroldo Conti’ in which he recounts the events linked to the detention and disappearance of the Argentine writer. He even attempts to bring to light through a consultation with the Admiral Emilio Massera, a member of the Military Junta, information demanding the whereabouts of Conti. ‘Habeas’ was criminalized and persecuted under the Federal Security Directorate in Mexico for being, supposedly, “financed by the Soviet Union and Cuba to liberate and lend support to ideological terrorists of Marxist-Leninism.”

Meanwhile, regarding the coup against the Popular Unity government of Chile in 1973, García Márquez proposed never to write again until the fall of the Pinochet dictatorship. He embarked on an international defense of democracy in Chile, defining himself as a socialist admirer of Salvador Allende.

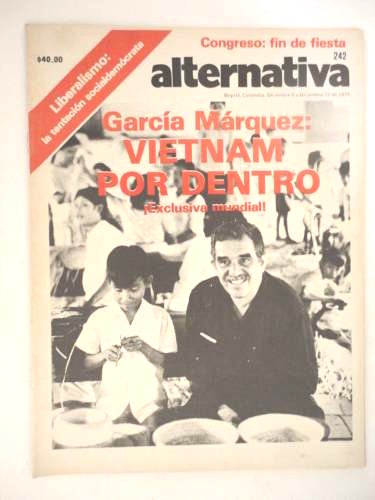

In 1974 Colombia, he published together with other intellectuals and writers, the magazine ‘Alternativa’, a magazine dedicated to the dissemination of critical thought and independent journalism that was persecuted and censored at the time. ‘Alternativa’ became one of the principal platforms from which Gabo published his radical opinions opposed to the official narratives on current revolutionary processes. Among these pages, they published initial versions of their reports on different global struggles: the dictatorship in Chile, the Cuban Revolution, the revolutionary Sandinista process in Nicaragua, the processes of decolonization in Africa, amongst others.

In 1977, at the request of Fidel Castro, García Márquez traveled to Angola to report on the development of Operation Carlota. He published a series of columns in the Colombian newspaper ‘El Espectador’, with an international perspective of the conflict where he established connections between the realities of the Global South divide. In the same format, he wrote the report ‘Inside Vietnam’ of his experience in already victorious Vietnam and the historic blow it had dealt US imperialism.

The solitude of Latin America

Now established as an international journalist, with an oppositional position to dictators and fascists, and a defender of human rights and the most oppressed, García Márquez was included in a list of military targets by Julio Cesar Turbay’s government in Colombia for supposedly having connections (never substantiated) with the urban guerilla group M-19. Several of the intellectuals included in this list were imprisoned and tortured, as was the case with the sociologist Orlandes Fals Borda. Upon learning that his name was amongst the targets, Gabo decided to permanently exile in Mexico, where a year later, he was notified by the Swedish Academy of Letters that he’d won the Nobel Prize for Literature, making him the first and only Colombian to have been awarded a Nobel prize.

In his acceptance speech for the prize, García Márquez once again took advantage of the podium to emphasize the meaning of winning this prize in the socio-political context of the continent. In his speech entitled ‘The Solitude of Latin America’, he launched a strong criticism of Eurocentrism and colonialism that was even as valid in the twentieth century as it would have been in the era of the Spanish Chronicles of the Indies. He drew on the entire history of oppression and plunder, recounting the freedom struggles from every corner of our continent, and reiterated the unwavering sovereign right to decide our own destiny. But far from wanting to draw from the play- book of imperialism, Gabo pondered a series of questions in a way that only he could:

“Why is the originality so readily granted to us in literature so mistrustfully denied to us in our difficult attempts at social change? Why think that the social justice sought by progressive Europeans for their own countries cannot also be a goal for Latin America, with different methods for dissimilar conditions? No: the immeasurable violence and pain of our history are the result of age-old inequities and untold bitterness, and not a conspiracy plotted three thousand leagues from our home. But many European leaders and thinkers have thought so, with the childishness of old-timers who have forgotten the fruitful excess of their youth, as if it were impossible to find another destiny than to live at the mercy of the two great masters of the world. This, my friends, is the very scale of our solitude.”

With this declaration of principles, which would paint a target on the back of any Latin-American, García Márquez traced the path that he would follow from the 1980s until his death, which could be summarized by increasingly supportive and internationalist ideas as a writer and journalist.

By 1973 he had already joined—together with other writers like the Argentine Julio Cortázar—the ‘Bertrand Russel Tribunal’ where they denounced the atrocious crimes committed by the United States in various parts of the world, especially in the context of the Vietnam War, and the nefarious effect of the imperialist interventions in countries like Panama and Nicaragua. On Panama, he joined calls for the reintegration of the canal, and on Nicaragua, in addition to his public support for the struggle of the Sandinistas against the Somoza dictatorship, in 1983 his published a key intervention on the preparations of the USA to invade the country from Honduras, information that he had acquired thanks to sources that he’d met as a correspondent in New York. After publishing this information, it was taken up by important newspapers in the US, like ‘The New York Times’ and ‘Newsweek’.

While continuing his internationalist work through the 1980s, at the same time García Márquez expressed his support for the political resolution to the social and armed conflict in Colombia, where he participated as a mediator in the different peace talks between the various leaderships of the National Liberation Army (ELN), the 10 April Movement (M-19), and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Over the years his friendship with Fidel Castro strengthened not only through their personal bond, but also through the connection with the revolutionary process of the Cuban people and the necessity to support it. Consequently, in 1986 Cuba, together with the Argentine film-maker Fernando Birri and Cuban director Julio Garcia Espinosa, they established the San Antonio de los Baños International Film and Television School, with the aim of founding a school for students from Latin America, Asia, and Africa. The school was created alongside the Foundation for New Latin- American Cinema, chaired by García Márquez, which sought to build a foundation to support and fund audiovisual production across the continent. In the same spirit, in 1994 he established the Foundation for New Ibero-American Journalism in Cartagena de Indias, that since its formation has developed training programs and stimulated the creation of a journalism in Ibero-America.

Throughout his life, García Márquez continued to stand by the side of popular uprisings in the continent. In 1999, he met comandante Hugo Chavez in Cuba, already president of Venezuela, on whom he wrote an extensive article titled The Enigma of the two Chaves. While in 2006, García Márquez—adhering to the ‘Panama Proclamation’ put forward in the Latin-American and Caribbean Congress for the Independence of Puerto Rico by a diverse range of intellectuals and artists from the continent—demanded the cessation of North-American colonialism on the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico.

With the defense of human rights as a flag, and with socialism for Latin America and the Caribbean as a horizon, García Márquez traced with pen and his life a path as original as it was difficult, one which he named as “the best profession in the world”. Journalism, but in his case a militant one, and committed to the reality of events and their impact on the people of the world, led him to be the antithesis of that meaningless maxim referred to as ‘objectivity’ so often repeated in journalism schools:

“I have clear and firm political convictions, sustained, above anything else, by my own sense of reality, and I have always said them publicly so that one can hear them if one wants to hear them. I have been through almost everything in the world. From being arrested and spat on by the French police, who mistook me for an Algerian revolutionary, to finding myself trapped with Pope John Paul II in his private library because he wasn’t able to turn the key in lock. From having eaten the leftover scraps from a Paris bin, to sleeping in the Roman bed where King Alfonso XIII died. But never, by neither fish nor fowl, have I allowed hubris to let me forget that I am nothing more than one of 16 children of the telegraphist from Aracataca. Everything else derives from that loyalty to my origins: my human condition, my literary luck, and my political integrity”.

Originally published in Spanish. Translation to English by Rohan Rice.