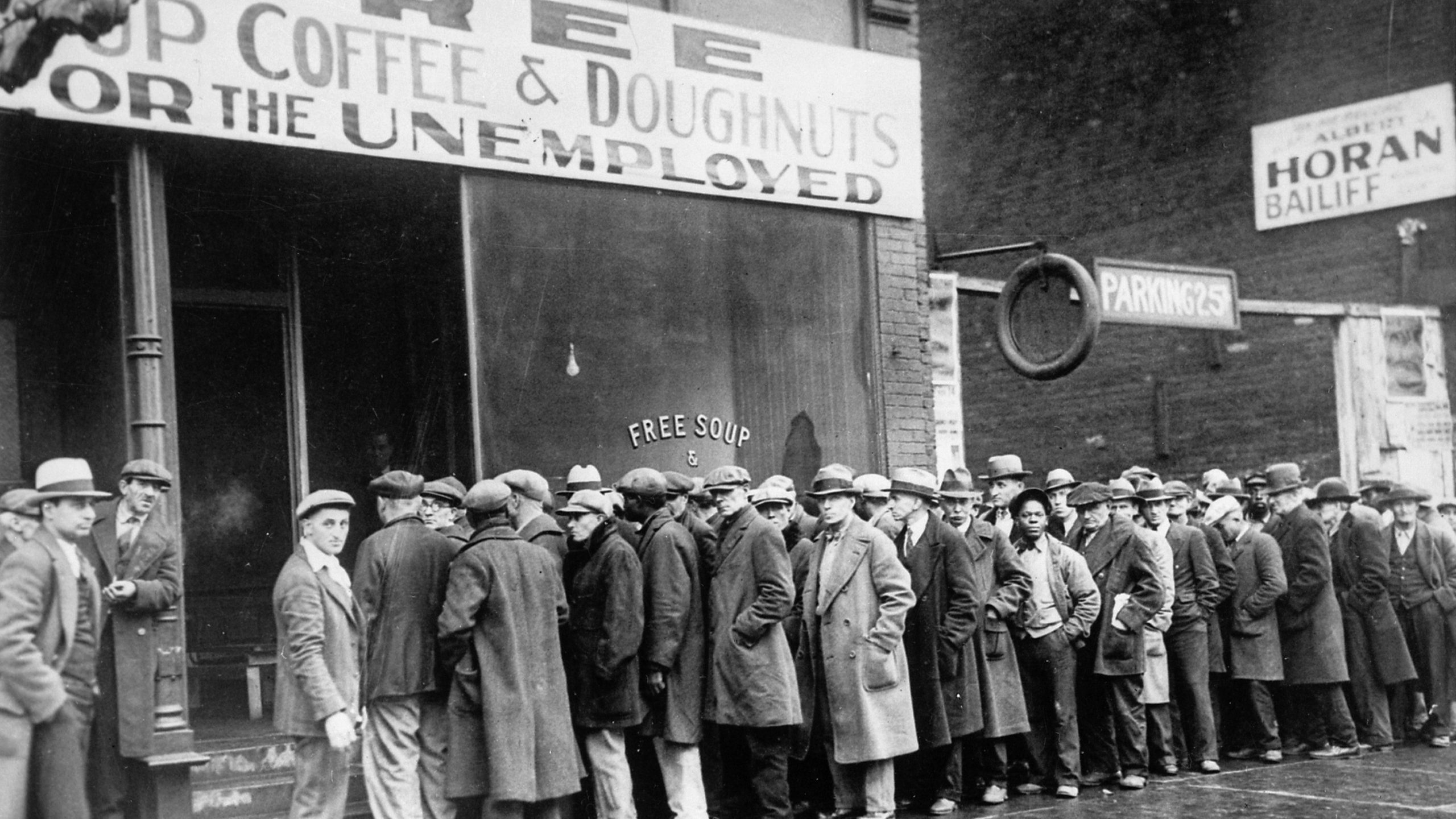

Did the Great Depression of 1929 have an impact on people’s genetics? This sounds an enthralling question and scientists have now found more information on this issue. In research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), it was reported that the economic recession impacted how people would age, even before they are born. The findings suggest that the cells of those conceived during the Great Depression show signs of faster ageing.

The question arises as to how the scientists map the genes of people conceived almost a century ago and how did they come to this conclusion? The answer lies in a field of genetics known as Epigenetics. This refers to how the environment shapes genetic expression. There are chemical markers attached to the DNA which profoundly impact when and how much a gene will be expressed in a cell. The researchers of the latest paper claim that the pattern of such markers that they uncovered can be linked to the conditions of faster ageing as well as a chronic ailment.

The PNAS paper, published recently adds to the body of research on how exposure to conditions of hardships like stress and starvation when a baby is conceived can shape their health for their whole life. Co-author of the study, Lauren Schmitz, who is an economist at the University of Wisconsin commented that the “findings highlight how social programs designed to help pregnant people could be a tool for fighting health disparities in children.”

Patrick Allard, an environmental epigeneticist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study said, “although the study is far from the first to link big historical events to changes in the epigenome, the fact that the signal appears in data collected from people in their seventies and eighties is mind-blowing.” He also said that the findings are potentially likely to get included in the textbooks.

It should be noted here that in 2008, it was reported that people who were conceived during a famine in the Netherlands had a different epigenetic make-up than those conceived during another time period. Those who were born in the Netherlands during this famine that occurred at the end of the Second World War had a higher rate of illness in the later parts of their lives. This was intriguing for geneticists and they suspected that malnutrition associated with the famine affected the epigenome in the early development period which had a permanent effect on how they process foods. Since then, we have numerous animal studies linking early exposure to pollutants or even stress giving rise to a variety of epigenetic alterations that can impact many important aspects including brain development.

Animal studies are helpful in deciphering how environmental factors alter epigenetic traits and have a life-long impact. However, finding these sorts of traits in humans has been extremely difficult. Scientists have discovered one way of doing it—they look back to major historical events and study how those events impact the biology of people later in their lives.

The team of researchers that attempted to link epigenetic changes among those conceived during the Great Depression compared markers of ageing of around 800 people who were born in the 1930s. The researchers found that they have a pattern of epigenetic markers that induce faster ageing of their cells. They also found that this epigenetic pattern was reduced amongst those who were in better condition despite living in the United States of America during the 1930s.

The results suggest that a biological foundation was laid even before birth among the children of the Great Depression which affected their rate of ageing in later life. Ainash Childebayeva, a biological anthropologist at the Max Plank Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, commenting on the findings said in a statement, “It’s not clear whether diet, stress or some other factor drove the accelerated ageing, and without being able to go back in time and tease apart those effects, it will be hard to pin down the biological mechanisms behind the signal. Nonetheless, these kinds of studies are really important because they highlight how early development matters for health and disease outcomes later in life.”