Indian prime minister Narendra Modi on July 2, Thursday, addressed soldiers in Nimu in the Leh region of the Himalayas. The speech was significant as it came just a few weeks after the clash between Indian and Chinese soldiers in the Galwan Valley near the Line of Actual Control that serves as the de facto border between the countries. It also came a few days after India banned 59 Chinese apps, including the popular TikTok, which was seen as the first salvo in a trade war.

Prime minister Modi, while not naming China, delivered a stinging rebuke to expansionism and declared that expansionist powers have always lost or withdrawn. The irony of Modi speaking about expansionism even as India is moving close to the US was not lost on critics.

That said, the implications of the clash in the Galwan Valley on June 15 continues to be felt. 20 Indian soldiers were killed and nearly 70 soldiers were injured in what is being called a “fist fight.” The Chinese army reportedly suffered casualties too though there are no clear numbers regarding this. These were the first combat deaths on the border since 1975.

The reasons for the “fist fight”, in which stones, sticks and other instruments were used, are not clear even after a “clarification” was provided by Indian prime minister Narendra Modi in his address to the nation on June 17. Before the address, the media was reporting Chinese intrusion into the Indian side of the LAC. The intrusion was reported in the Indian union territory of Ladakh, with the media valorizing the Indian soldiers’ attempts to regain that “lost territory”. However, according to the Indian prime minister on June 17, “no one has crossed the border and entered India.”

Modi was considered technically correct in his assertion because the LAC is not a fixed border. Both China and India have not succeeded in demarcating it since its creation after the 1962 war between the two countries. It is largely based on the perception of who controls what. Armed forces, both Indian and Chinese, keep` on moving in the region, knowingly or unknowingly “violating” the territory of each other. It is largely up to the governments at the time to make such a violation an issue in the media or try to address it mutually through local-level coordination. Every year, such resolutions are made between both the countries and most of the time, it does not become a public issue.

India and the containment of China

Then what happened this time? Why did both the states make it an issue and why did things go to the extent of a “fist fight,” leading to the first set of casualties in decades? It seems both sides have their reasons. For the Indian side, any diversion from its failure to deal with the COVID-19 disaster is welcome. With close to 700,000 infections and nearly 20,000 deaths, COVID-19 has exposed the failures of the neoliberal policies adopted by the successive governments in general and the Modi government in particular. A limited incident at the border with China does serve the purpose of a diversion. From the Indian perspective, such an engagement would not even require any sustained military follow-up, unlike say, an engagement with Pakistan where domestic opinion would force India to show military superiority. Even hawks in the Indian establishment know that the government cannot risk a war with China. Hence, there won’t be any real pressure on the government to escalate the military option.

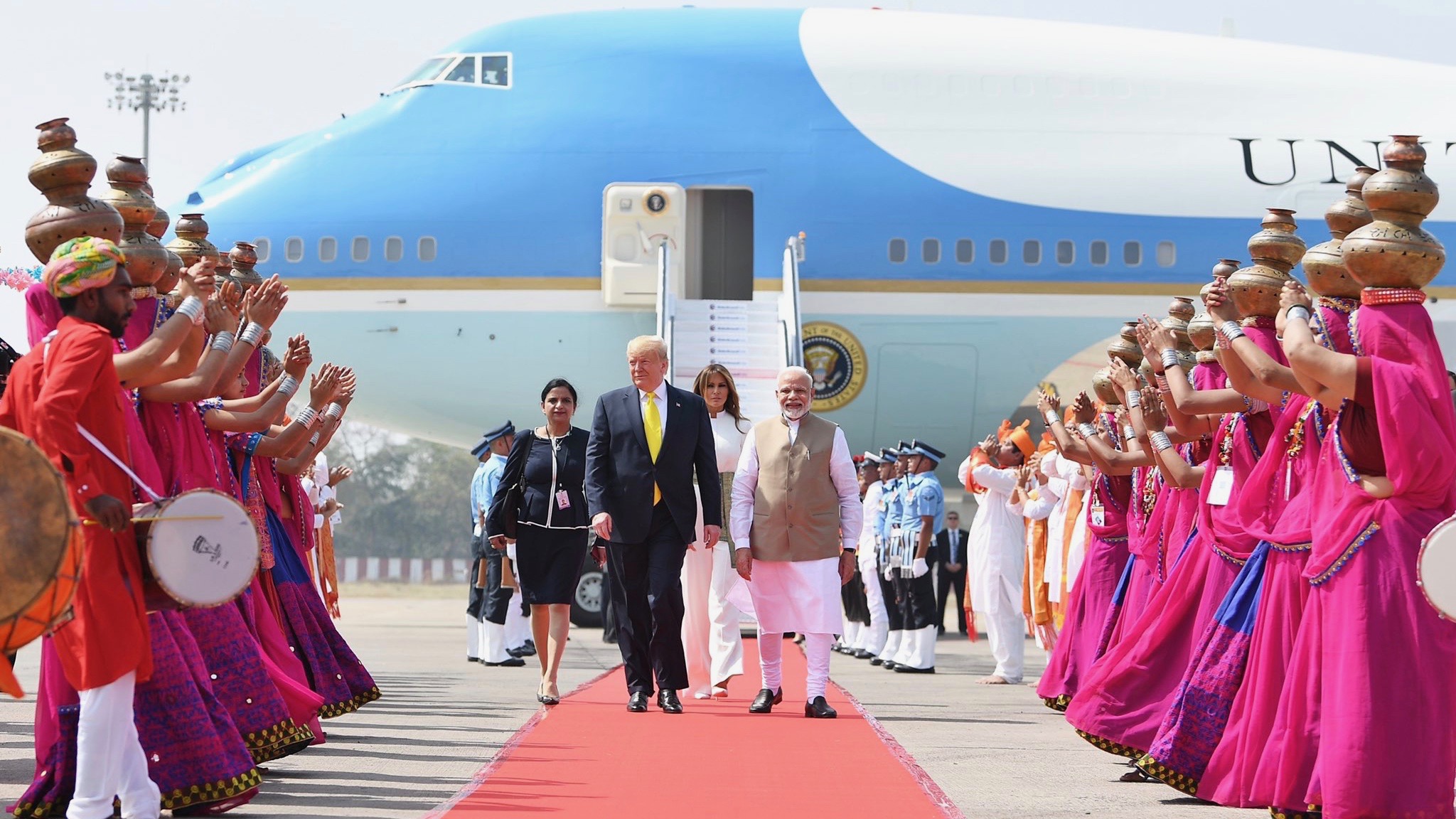

However, the possible diversionary nature of this incident is only one aspect. Assertion at the LAC has been part of both countries’ policy since 1962 itself. This has gained greater significance in recent times, particularly because of India’s increasing hobnobbing with the US and its allies. The containment of China is a declared foreign policy goal of the US. India’s joining the so-called Quad with the US and its two allies, Australia and Japan, clearly provides reasons for suspicion as far as the Chinese are concerned. The Indian position on the South China sea has acquired a more aggressive tone in recent times. India in the past reportedly had concerns about China’s involvement in Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port. Thus, it is understandable that China would not take lightly India’s support for the US and its allies’ presence in the South China sea.

India signed a treaty with Australia in June according to which they will have joint naval exercises and Australia can use Indian military bases. India already has such treaties with Japan and the US.

There are several indications about Indian hostility towards China. For instance, the Indian home minister Amit Shah said in the parliament last year that he was ready to shed blood to regain Aksai Chin, the Chinese controlled region between Tibet and Ladakh. Another key development was the construction by India of the all-weather Darbuk-Shyokh-Daulat Beg Oldie Road last year. This road significantly improves Indian access to the Daulat Beg Oldie airbase, the highest in the world, which is very close to the LAC.

There are other small but significant factors which would have provoked China. India became the head of the WHO executive board in May and changed its long-held position and supported the Australian bid for a fresh inquiry into the origin of the coronavirus pandemic despite Chinese objections.

In April, India amended its rules on foreign investment according to which investment from a neighboring country needs government approval. The reason given is to prevent the attempt to opportunistic takeover of companies affected by the coronavirus-induced lockdowns. However, it was clear that Chinese companies were the targets of such hostility.

This move is on similar lines to the US position taken vis-à-vis Chinese companies in the recent past. The fact that India also toed the US line in blaming China for the outbreak of the pandemic could also be a factor in rising Chinese apprehensions towards India.

Hyper-nationalism in India

There is very little doubt that Donald Trump’s so-called Trade War with China is being replicated by some European countries, as well India, albeit at a much lower level. Apart from the official policies, Indian media and political activists have time and again tried to portray China as an enemy. The colonial bait, created during the formative years of nationalism in both the countries, have taken deeper roots in India due to the persistence of a sense of inferiority post the defeat in the 1962 war. It is no wonder that the attempt to portray Coronavirus as Chinese Virus has been very successful in India. Few media channels or “experts” have attempted to revisit the role of the British colonial period in creating the border problem in the first place. Since there is a lack of acknowledgment of the past, there is no serious attempt to address it now.

India and China have not had serious engagements over the border for decades. The resolution is not forthcoming because no serious attempts were made by either side to undo the colonial impositions. India in particular takes the colonial demarcations as a given due to the kind of nationalist rhetoric in which Chinese are portrayed as aggressors and pre-1962 history is completely blurred.

Victims of hyper-nationalism, the Indian media keeps making calls for the boycott of Chinese goods and “teaching Chinese a lesson.” The few rational voices which are attempting to talk about the facts are either shut down by the accusations of being “anti-nationals” or are lost in the cacophony.

Facts

Here are the facts for those who want to boycott Chinese goods or teach Chinese a lesson:

- India imports more capital goods than consumer products from China. These are used to make goods which are substantial part of India’s exports. India can stop imports from China only at its own peril.

- India is not on the list of top export destinations of Chinese goods whereas China is the third largest destination of Indian exports.

- Nearly USD 200 billion worth of Indian goods cross the South China Sea annually.

- India’s defense budget is USD 74 billion whereas China’s defense budget is USD 178 billion

- Last but not least, border disputes between India and China can easily be fixed between both the countries as it does not involve any significant exchange of population.

The first three points highlight the need for strengthening economic cooperation between both the countries. From the point of view of the conflict resolution, the focus should be on the fifth point. India does not need war with China, economically or militarily.

There is a growing fear among the US and its allies of the challenges to their hegemony by an increasingly assertive China. The imperialist system built over neo-colonial/neoliberal occupation of economic decision-making in most of the countries and the palpable threats of wars/sanctions suddenly looks threatened due to the possible rise of a new pole. Their propaganda machine has been working against China for long. However, in their desperation, they are looking for indirect military confrontations.

A large section of western scholarship is devoted to portray India as the “emerging superpower”, and pitching it against China as “counterbalance”. The propagandist scholarship in the western world tries to create a false moral binary in which India as the “world’s largest democracy” is standing up to “authoritarian China”. It tries to create a false sense of pride among Indians by equating their country with “world’s greatest democracy” i.e. the US and calling them “natural allies”. Though it is difficult to not fall for such flattery at a time of hyper nationalism, it is high time India gets this right. India and China are countries with a history of being victims of imperialist aggression and there cannot be a common cause with the imperialist US. India needs to realize these imperialist chess games and refuse to be a pawn.

The autonomy of India’s foreign policy and well-being of the Indians should not be sacrificed at the altar of a seat on the imperialist councils. India’s historic solidarity with the victims of colonial loot and occupation should not become victim in the race for tags bestowed to us by the western propaganda. India and China are two sovereign and independent countries with their own set of strengths and problems. They need to sit and talk to resolve their issues on their own.